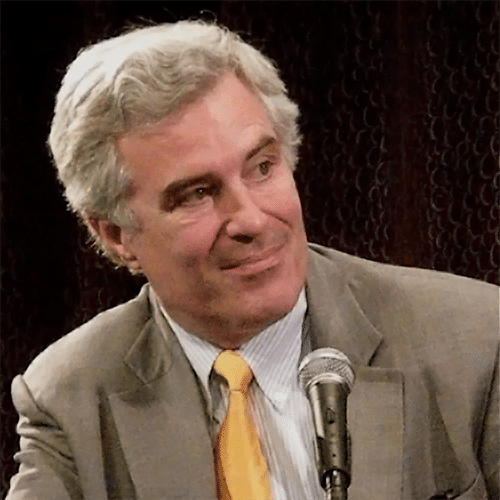

Atticus LeBlanc is the founder of Padsplit, a technology platform dedicated to affordable housing, with no barriers of entry. Atticus, who studied architecture and urban studies at Yale, has been an affordable housing advocate and real estate investor for over a decade, with a company that owns and manages over 550 affordable residential units. But he founded Padsplit with a much bigger goal in mind. He wants to dramatically change how we address affordable housing by using space that is now under-used – whether in our own house or a rental property. He wants to make every available room a safe, clean home for someone who really needs it, all while providing a fair return to homeowners.

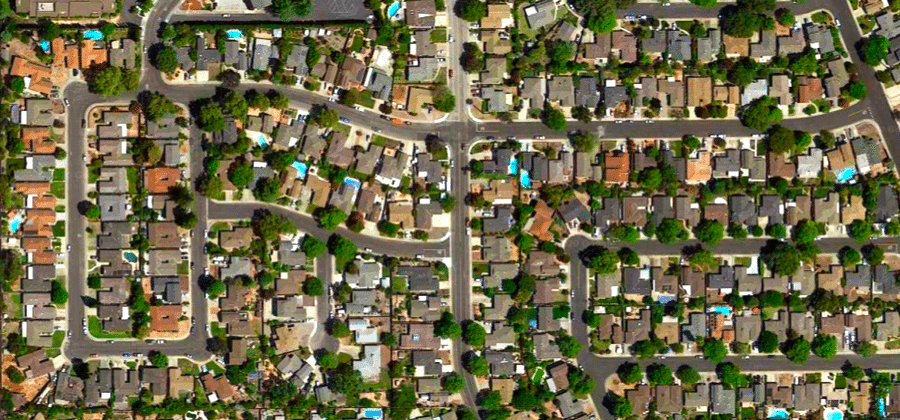

PadSplit’s platform allows homeowners to list a room, or to work with local contractors to reconfigure a house to optimize the space for multiple tenants. PadSplit houses typically offer five to eight furnished bedrooms, with shared bathrooms, kitchen, dining, and laundry rooms (no living rooms), with all utilities, internet and a cleaning service included, for a weekly rent. To rapidly provide new affordable housing in our changing economy, Atticus wants PadSplit to take hold in a really big way. So, he’s planning to grow the 1,100 rooms that are on PadSplit today, to many hundreds of thousands of rooms. PadSplit is his moonshot.

Atticus has written in-depth Op-Ed pieces for the Forbes Real Estate Council blog, is the co-chair of ULI’s UrbanPlan Education Initiative, and he co-chaired the Design For Affordability Task Force in 2018.

Insights and Inspirations

- Atticus wonders how we’ll ever catch up on the affordable housing we need to build if we don’t think differently.

- Every spare, unused room can be a fresh start, and safe home, for someone who needs it.

- PadSplit is a private market solution to a problem that is generally managed inefficiently with subsidies.

- PadSplits are generally located near public transit.

- No traditional corporate leases. No deposits. Month to month. Fully furnished. Stay a month or stay a year. People can live in PadSplits to live close to their job (where they otherwise may not be able to afford a unit), or simply to get back on their feet.

Other Information

- Atticus has three rituals that keep him grounded: Journaling, exercise and nightly dinners around the table with his family. He also loves fishing and backpacking whenever he can escape from his work routine.

Read the podcast transcript here

Eve Picker: [00:00:09] Hi there. Thanks so much for joining me today for the latest episode of Impact Real Estate Investing. My guest today is Atticus LeBlanc, founder of PadSplit, a technology platform dedicated to affordable housing. Atticus has been an affordable housing advocate and real estate investor for over a decade now, his company owning and managing over 550 affordable residential units. But he founded PadSplit with a much bigger goal in mind. He wants to dramatically change how we address affordable housing by using every space that is underused, in our own house or in a shared home. He doesn’t care how. Every room is a safe, clean home for someone who really needs it. You’ll want to hear more. Be sure to go to EvePicker.com to find out more about Atticus on the show notes page for this episode. And be sure to sign up for my newsletter so you can access information about impact real estate investing and get the latest news about the exciting projects on my crowdfunding platform, Small Change.

Eve: [00:01:26] Hello, Atticus. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Atticus LeBlanc: [00:01:30] Absolutely. Pleasure to be here, Eve. Thank you for the opportunity.

Eve: [00:01:33] Yeah, I’m really looking forward to that conversation. Because you’re doing something pretty unusual. You started a company called PadSplit, and I’m wondering why you started it.

Atticus: [00:01:45] Sure. Yeah. So I think ever since I was a kid, I enjoyed solving problems. And maybe charging at windmills bigger than, bigger than where appropriate at any given time. And this has just been a really big windmill. I’ve been in in real estate my entire career here in the Atlanta area, going on 18 years now. And have been an entrepreneur for the last 15. And then in housing, specifically, for the last 12. As an entrepreneur in the housing space, I came to see a lot of what I felt was wrong with the industry, and the growing, let’s just say, affordable housing crisis for lack of a better word, and lack of supply, and lack of customer discovery for people who were the front line workers within our communities. And folks who ultimately had to commute hours or several hours a day to be able to afford a place to live and get to their place of work. And so, when I got to a point in my career where I felt like I was comfortable financially and had built up enough of the real estate portfolio that could support my own family, this was kind of a moonshot endeavor to look at ways to really solve the underlying fundamental issues of housing, on affordability, not just in the Atlanta market, but trying to do so around the country, and potentially around the world.

Eve: [00:03:10] So, PadSplit splits pads, it’s a great name. What does a PadSplit house look like, typically, after you’ve finished renovating it?

Atticus: [00:03:21] If we’ve done our jobs well or if our owners and real estate investors have done their jobs well, it looks from the outside like any other traditional housing unit, whether that’s a single family home or apartment. On the interior, it’s a little bit different. But essentially it’s just geared to allow single person households or individual workers in our communities to be able to rent individual rooms rather than entire homes. So, because we, we’re a marketplace and we align incentives with real estate investors who are generally looking for higher returns, one thing that may be different is you’re typically going to see more bedrooms in a PadSplit home than you would in a typical home. And the reason for that is in a traditional rental home environment, or any home environment, you have a lot of inefficient, underutilized and unmonetized space. So, if you’re going to rent a property, there’s almost no cost included in the rent for the formal dining room, for instance …

Eve: [00:04:28] Right.

Atticus: [00:04:28] … or the home office. And there’s no reason why, given the fact that we have a lack of housing supply, that these spaces shouldn’t be utilized to actually house people. And so, what PadSplit does as a marketplace, it allows those spaces to be utilized on an individual contract basis with each one of those people who needs a place to live. And in doing so, also makes the home more profitable for those real estate investors. And so, the difference is you would see, instead of a formal dining room, you’d see that room converted into a convertible living area where you actually have a bed instead of a dining room table. And that owner is getting paid for it rather than not.

Eve: [00:05:11] So, by doing this, you can include traditional investors who get a return and you don’t need subsidies, you’re not relying on the government to produce affordable housing. Is that right?

Atticus: [00:05:24] Exactly. Exactly right. Yeah, and throughout my career I’ve worked with a number of more traditional affordable housing programs and have consistently been frustrated by …

Eve: [00:05:35] Oh, they are so complicated.

Atticus: [00:05:37] Yeah, it, well, not just the complication, but the time. The time and energy and effort that goes into creating those units, and meanwhile, we have an abundance of outside opportunity. Right? There is …

Eve: [00:05:52] I think also not just the time and energy. I’ve done some work like that, too, but it’s an industry that kind of hasn’t caught up to what people want today. So, it can be pretty inflexible.

Atticus: [00:06:03] Absolutely.

Eve: [00:06:04] About, you know, what an affordable housing unit should look like.

Atticus: [00:06:08] Yeah, I’d say there are two major issues with the affordable housing industry, let’s call it. And one is the fact that virtually every program is designed to limit profit. And where profit is created or treated as an enemy. And instead they will pay as a percentage of cost. It’s OK to get paid as a percentage of cost, but not as profit. And what you do is you misalign incentives there. Where an affordable housing developer who’s maybe redeveloping a property, they have a home with perfectly good kitchen cabinets, but if they’re getting paid on a percentage of cost, they are now motivated to spend those public dollars to replace those perfectly good kitchen cabinets with brand new ones, because they only get paid if they actually spend that additional subsidy. And I’d say, overall, in most of the programs I’ve worked with, they generally have that same ideology. That they need to pay a fee rather than thinking about what is the most efficient solution possible.

Eve: [00:07:15] Right.

Atticus: [00:07:16] The second issue is just customer discovery, in that if you look at the Low-Income Housing Program, for instance, which has been probably the most successful affordable housing creation program in American history, three million units over about 30 years, there’s still no customer discovery there, where they’re evaluating the needs of the individual residents. The rules that are governing what types of units are created are ultimately from a consortium of government officials with some private advice from developers, but almost never based around purely, OK, you are a person who is in need of housing – What exactly do you need and what is the most efficient way to create that?

Eve: [00:08:02] Right. Right.

Atticus: [00:08:03] And so as a result, you spend a lot of money creating something that isn’t necessarily geared towards the end customer.

Eve: [00:08:09] What do you include in a PadSplit room, and how did you discover what your customers want?

[00:08:15] Yeah. So, what’s included in a room, and really this goes hand-in-hand with what the customers want. Rooms are fully furnished. They include all utilities, Wi-Fi, laundry, telemedicine and credit reporting into one single bill. And that bill is charged on a weekly basis, or on individual pay periods when people get paid. And this came out of the customer discovery process when I was managing properties that I owned, and particularly in lower income apartments, I ran into situations where I saw people that would end up late on their rent and under eviction because ultimately they decided to pay a utility bill, a cable television bill, for instance, in the middle of the month, and didn’t have enough money left over by the time the first of the month rolled around to be able to make that payment. And it was mind boggling to me, initially, that why would anyone ever choose to do that? And as I dove a little deeper, it occurred to me, well, wait a second, you know, we’re obviously, we’re almost at the end of the month now, but if I asked you or anyone else, what day of the week does November first fall on? No one, almost no one would know off the top of their head.

Eve: [00:09:40] Right.

Atticus: [00:09:40] But we all know that today is Wednesday. And if I get paid on Friday, it’s very easy for me to budget around that.

Eve: [00:09:47] Right, right, right.

Atticus: [00:09:48] And at the same time, if I’m living paycheck to paycheck, then it’s very difficult for me, and me personally, I mean, I’ve long put a lot of my stuff on autopay just because I know I won’t remember. But if you don’t have the financial capacity to do that and you have to really be careful about your budgeting, it’s not easy when you have a cable bill that’s due on the 12th and a water bill that’s due on the 23rd and so forth and so on. And you start to compile all these bills. And people are just not spending their money as wisely as they should be because it’s not top of mind.

Eve: [00:10:26] Right, right.

Atticus: [00:10:27] And the prioritization of those expenses is not anything that’s easy to do. And then on top of that, as I looked at the traditional housing industry, and in a rental property where people would have to pay large upfront deposits, we all know that there’s a huge portion of the population that doesn’t have the money, doesn’t have any savings …

Eve: [00:10:48] Yes.

Atticus: [00:10:48] … to be able to do that. And so you really want to just wait around for them to build the savings so they can get the deposit? Or do you want to figure out a way to create easier access? And so, that’s really what we’ve done, is created lower barriers to entry for individuals who are in need of housing, but also kept the billings on a regular schedule that’s easy to remember so that they can afford them.

Eve: [00:11:11] Right, right, right.

Atticus: [00:11:11] And they don’t have to come up with those upfront costs to outfit their bedroom or apartment or house on the front end, that just further exacerbates their affordability issues.

Eve: [00:11:22] So, where you start your operations?

Atticus: [00:11:25] So, started here in Atlanta. I really kicked off my housing career, I’ve been in Atlanta now for 20 years, almost. I kicked off my housing career in late 2007, early 2008. Really a touch before that, but really just got into the swing of things before the crash had really been public, but it was clear that something was going on, and that home values were much lower than they should have been, although at the time I had no idea why, and no one could really tell me why. But it’s been a long time coming. And we’ve been working on this problem for a long time.

Eve: [00:11:58] You started in Atlanta. How many units you have now and where they located?

Atticus: [00:12:03] So, we have about 1100 units today.

Eve: [00:12:06] Oh, wow.

Atticus: [00:12:07] And they are still mostly in Georgia, although we have a handful of units in the Texas market. And we’ve got some in Alabama, we’ve got some in Virginia. And we’ll be making a larger push into, into the Houston metropolitan area, as well as a couple other markets here over the next several months.

Eve: [00:12:28] And what are your tenants look like? Who are they?

Atticus: [00:12:31] Here in Atlanta, our members, as we refer to them, average income is around 25,000 dollars a year. It’s the cashier at your grocery store, the barista at your at your coffee shop, the security guard at any local retail establishment or hospital, Uber drivers, Lyft drivers, administrators in various government offices.

Eve: [00:12:54] That is shocking. Administrators and government offices.

Atticus: [00:12:57] Oh, yeah. Yeah, I mean, we’ve we’ve had police officers. We still have some teachers. Average age is, is just under 40, about 39 years old.

Eve: [00:13:04] Oh.

Atticus: [00:13:04] About 60 percent single women. And here in Atlanta, we’re 97 and a half percent African-American. But yeah, I mean, I refer to this group of people really as the invisible population. But I challenge any of your listeners to just ask next time you’re in some sort of retail environment, or heck, your Amazon delivery driver. But the folks who work in your community, whether that’s a hairstylist or the, anyone at the grocery store, where do they live, ask them where they live. And I think you’ll be intrigued to find the answer. But it wasn’t until maybe five years ago or so, I really started to understand that you could be working full-time in this country and very easily be homeless.

Eve: [00:13:48] Yeh.

Atticus: [00:13:48] And just that there are almost no housing options available for people that earn less than around 35,000 dollars a year that are the traditional options without any subsidy.

Eve: [00:13:57] I always make a habit of asking Uber drivers,= if that’s the full time job. And I’m, I’ve been stunned hear who has to moonlight, Uber driving …

Atticus: [00:14:09] Yeh.

Eve: [00:14:09] … over the years to make ends meet or to pay for groceries or to make the rent payment. It’s pretty shocking …

Atticus: [00:14:17] Yeh.

Eve: [00:14:17] Especially on the West Coast.

Atticus: [00:14:20] Yeah, definitely. I mean, even here in Atlanta, which is a relatively affordable city, we have a young woman who’s now been with us for almost three years, who works as a pastry chef in Midtown. But before PadSplit, she was commuting an hour and a half each direction …

Eve: [00:14:35] Oh, wow.

Atticus: [00:14:35] … to get to her place of work. And then I remember the last time I was in San Francisco asking my Uber driver where he lived. And he lived with his family in Fresno, three hours away. But then four days a week, he shared a studio apartment in Daly City near the airport. And that was how he made it work. So that he could spend some time with his family in Fresno. It’s incredible when you see the lengths that people have to go to just to find reasonable housing. And these really are people that our economy relies on on a regular basis, but really just go unnoticed.

Eve: [00:15:08] That’s pretty heartbreaking. So, I have to ask one question as an urban designer and architect, what do the neighbors think …

Atticus: [00:15:17] Yeh.

Eve: [00:15:17] … when you renovate the house?

Atticus: [00:15:19] Depends very much on the neighbors, right?

Eve: [00:15:21] Right.

Atticus: [00:15:21] It would be no surprise to anyone that we have NIMBY opposition, you know, folks who say not in my backyard.

Eve: [00:15:28] Well, I’ve heard, Atticus, that quite a few people say, on my podcast the last month that NIMBYism is probably the biggest reason why we’re in this predicament.

Atticus: [00:15:39] Oh, unquestionably. Yeah, I don’t deny that at all, and it’s frustrating. I mean, with with a lot of those those conversations where people say, OK, well, yeah, I think the person who works in my grocery store should be able to live here. And my question is always, do the people who serve your community deserve an opportunity to live there? And almost no one ever says ‘no’ to that question. Right? But they will say, well, yeah, but the government is going to fix that.

Eve: [00:16:11] Right.

Atticus: [00:16:12] And, or the cities are working on that problem. And I don’t think anyone really has an idea of just the scope and the depth of the issue and how bad things really are. And the fact that if we as a society are not working to change these issues on our own, nobody’s going to get anything done. And so, yeah, I mean, absolutely, there are lots of neighbors who, under the guise of, quote unquote, protecting the integrity of single family neighborhoods, which they conveniently forget, like all of those zoning codes were based in systemic racism going back a hundred years, that it’s OK for all of this space to go to waste while you have people who are working full-time, that are living on the street or commuting three hours.

Eve: [00:16:58] Right.

Atticus: [00:16:58] And I mean, that’s a real difficulty and something that I think we as the community or as a nation of communities and neighborhoods ultimately have to decide where the line in the sand really is. And at what point do you say, OK, in our country, everyone should have equal access to opportunity and housing opportunity almost goes without saying, but what are we willing to do to live out those ideals?

Eve: [00:17:27] So, you’ve thought a lot about affordable housing solutions. Why this one?

Atticus: [00:17:32] Well, for me, I was intrigued by private market solutions that didn’t require subsidy programs. And don’t get me wrong, I’ve worked with a lot of subsidy programs and particularly housing choices and still am an owner of a number of properties that work with housing choice participants. But just the time, right? It was, how quickly could I do something today that could create a groundswell of support and address the problem as expeditiously as I felt like it needed to be addressed. And so that’s really the reason why I looked at private market solutions, was because I knew that if you could align those incentives to just create more efficient market opportunities, then I had already seen over the course of my career how strong some of those forces could be. Where here in Atlanta, I watched entire neighborhoods change over the course of just two or three years because of the actions and investments of not one large company, but tens or hundreds of independent individual real estate investors and entrepreneurs. Sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

Eve: [00:18:43] Yeh.

Atticus: [00:18:43] And so, the idea was, OK, well, right now we are decrying the gentrification and displacement in a lot of these communities. And I agree, that I think in a lot of ways, the displacement especially, is heart wrenching and contributes to the same problems that we’re seeing with people having to move further and further away from their places of work. But what if we could take the same group of individuals who really are just pursuing their own best interests, which we can’t expect them not to. And you said, OK, well, instead of contributing to gentrification and displacement in these areas, what if I gave you another option for investing that allowed you to create more affordable housing? And if you could make affordable housing more profitable than the other alternatives that people had so that the best option available was also one that was a societally good thing and created positive social change for these largely marginalized groups, then those investors would absolutely pursue those. And that was really the thesis that led me to create that split in the way that we’ve done.

Eve: [00:19:44] How much do your tenants, or your members pay per month compared to a unit like what, that they would have to go out and get in the marketplace?

Atticus: [00:19:53] Yeah. And it’s not apples to apples, because our units are all-inclusive.

Eve: [00:19:58] No, of course not. There’re furnished, and electric and utilities and everything, right?

Atticus: [00:20:02] Exactly. Yeah. But it’s about 600 dollars on average, across our portfolio, that people pay on a monthly basis.

Eve: [00:20:10] How much vacancy do you have, because that’s always a good indicator.

Atticus: [00:20:13] Yeah. So, right now we have about 45 rooms or so that are available, so we stay pretty well full. Of course, back to the customer discovery and user question. What we found too is if you’re new to town, if you come here and you’ve got a job, you don’t really want to sign a 12-month lease, you’re trying to figure out what part of town you want to live in.

Eve: [00:20:37] Yes.

Atticus: [00:20:38] And so …

Eve: [00:20:39] It’s like co-work, for housing.

Atticus: [00:20:41] Yeah, similar. Similar. Yeah. I mean, it’s but so our terms are certainly shorter. On average, we still see nine months as an average term …

Eve: [00:20:50] Yeh.

Atticus: [00:20:50] But we absolutely have folks who come to town and are trying to get their bearings or get their feet under them, or maybe they’ve just been through some sort of traumatic situation like a divorce or the death of a loved one. And they don’t need something long-term. They need an affordable place to stay for three months.

Eve: [00:21:08] Right.

Atticus: [00:21:08] And so we see those as well. And that certainly contributes to the amount of vacancy as well. But, yeah, we stay pretty well full.

Eve: [00:21:16] And I have a feeling that you chose this path, as well, because it’s a way to scale what you’re doing. I’d love to hear your hopes on scale.

Atticus: [00:21:25] Yeah, I certainly had no business starting a technology company.

Eve: [00:21:30] Kind of like me.

Atticus: [00:21:31] I am a real estate Neanderthal. But I was intrigued by what I had seen AirBnB do over the preceding 10 years, in terms of, just how individual hosts around the world were able to take this model and run with it. And I wanted to do the same thing with much more positive social impact for affordable housing. And I wanted any real estate investor, or homeowner, candidly, or housing provider of any kind, anywhere, to be able to pick up these sets of tools and provide affordable housing in their communities, regardless of what their thesis may be. If they wanted to create housing for farmers or teachers or employees at a certain facility, that they would be able to use these same sets of tools to be able to do that. And that was really, the major reason why I started PadSplit as a technology marketplace as opposed to a real estate company, was because I certainly didn’t fancy creating this mega-corporation that owned thousands and thousands of homes. And, oh, by the way, even if we did, that still wouldn’t be near the impact that I was trying to create in the world.

Eve: [00:22:49] Do you own any of the buildings yourself at all or are they really …

Atticus: [00:22:53] Personally, I have two. The first prototype and then I have one other one. But other than that, no. We have maybe 65 or 70 different owners of all the properties.

Eve: [00:23:05] Oh.

Atticus: [00:23:05] Anyone from an individual homeowner, all the way to institutional or sub-institutional investors. I do have one room in my personal home that I rent through the platform. We don’t really count that one.

Eve: [00:23:17] So, how do you manage those building owners? Because I can imagine some bad ones might creep in.

Atticus: [00:23:24] Well, a lot of that is baked into the model. Right? Where we don’t do traditional corporate leases the way that other similar companies have done, where we’re the ones making the improvements. The owners are ultimately sharing in the profitability. So, they see a direct correlation between the quality of the unit and their bottom line. And that’s really, I think, important about aligning those incentives. And they are the ones that are purchasing, maintaining and renovating those properties. And then also to maintain accountability, a big part of the platform, and this was absolutely from AirBnB, giving the residents in those homes or the members in our platform the ability to rate and review both maintenance and quality of those homes.

Eve: [00:24:05] Um Hmm.

Atticus: [00:24:06] So, kind of creating …

Eve: [00:24:09] That’s encouragements.

Atticus: [00:24:10] … creating 360 degree accountability where not only are those posts motivated by the bottom line, but they’re also accountable to the members inside those homes as well.

Eve: [00:24:22] You touched on systemic racism and I know you’ve written about this and thought about this. And I’d like to know what you think of some of the key examples of racism in housing policy that exist today and that have made this problem worse.

Atticus: [00:24:40] It’s not really a question of what I think. It’s just a question of a history lesson. And there are a couple of points there. One, if you look at any historic neighborhood today compared to what the population makeup was 100 years ago, or call it turn of the, turn of the 20th century, what you’ll find is that there was a much wider distribution of family makeup in those neighborhoods then, and housing choices there, than than there are today in those same neighborhoods. Because since the 1960s, we’ve as as a nation really forced this idea of single family home. And that’s been repeated over and over and over, where one family, one home, in spite of the fact that you look at 35 percent of the population as single person households. Today. And meanwhile, our home sizes have just continued to increase, even though family size continues to decrease. So, you had this this extreme mismatch. How that relates to systemic racism is this, in that, whether you’re looking at as as Richard Rothstein analyzed in Color of Law and has been written about by a number of other publications, the foundation of these zoning codes, when things started to change in really, whether it’s L.A. 1908 or Buchanan in 1917, they stemmed from trying to segregate neighborhoods based on race. Like, that was the foundation of zoning. And if you acknowledge that at any point in our history, regardless of if you believe that it’s happening today, but at any point in our history, if our culture has contributed to wealth inequality on the basis of race, at any point, if that has contributed to our current inequality of income based on race, then you also have to acknowledge that because these housing policies are based around income, they’re also based around race. And so if I say in a particular neighborhood, you who may be lower income and maybe a single person are not allowed to live here by virtue of the fact that the average home is going to rent for 3,000 dollars, I’m discriminating based on race, in that situation. And so, by limiting the diversity of housing stock and housing choices, we are absolutely discriminating based on race while we are discriminating based on income. And the great irony is, across racial groups, there are very few communities who have any concern about discriminating based on income. But very rarely do the same folks ever acknowledge that because you’re discriminating on income, it also means that you’re discriminating based on race, but it’s just, it’s just a fact.

Eve: [00:27:29] Yes. Yup. OK, so then what’s what’s the biggest challenge you’ve had?

Atticus: [00:27:37] Oh, let’s say, the only, only one, huh? Yeh.

Eve: [00:27:41] One of them.

Atticus: [00:27:43] Listen, I mean … It’s a massive problem. And I’d say, the single biggest thing is, is anticipating and managing human behavior at any level of scale. Right? Whether that is relationships with members inside the homes, whether that is relationships between the members, or just the home and people in the neighborhood. And the sheer amount of effort necessary to maintaining all those relationships. Or the foresight to build in structures and processes that align behaviours appropriately. And we’ve done a lot of work on this and certainly put a lot of thought into it. I mean, listen, we sit at this intersection where we are involved in people’s lives 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at the very base of Maslov’s hierarchy of needs, in terms of just the need for safety and shelter.

Eve: [00:28:49] Yeh.

Atticus: [00:28:49] And so, it is about as big a problem as I think I could have ever tried to tackle.

Eve: [00:28:55] Yes, I’d agree with that.

Atticus: [00:28:56] And just the sheer complexity of those different interactions is the single hardest thing in my mind.

Eve: [00:29:02] So, what’s your big, hairy, audacious goal with this, with PadSplit?

Atticus: [00:29:08] For me, it’s always been that you can solve at least a significant portion of the housing crisis on a national and global scale. The big, hairy, audacious goal is that it becomes a household name that just becomes commonly accepted. That if you are in an apartment or if you are in a home and you have extra space, why on earth wouldn’t you trust another individual to lease that space from you? In the same way that I think ride sharing to hitchhiking. Where 20 years ago you would never imagine getting the back of a stranger’s car, whereas today we do it all the time. And those activities are not fundamentally any different. What’s different is the fact that you, as a customer of that service, trust that stranger that you’re getting into the back of a car with. And so, the big, hairy, audacious goal is that same paradigm exists for housing. Where you trust that you can use this platform and and allow someone else into your home without really missing a beat. And that’s just obviously a wholesale change to the way that we think today about, quote unquote, strangers. And if we can empower access to those opportunities, both as a user of housing or as a provider of housing, and to empower those users to become providers eventually and build their own income and wealth, that’s really what we’re setting up for. And we want to make sure that those opportunities exist everywhere.

Eve: [00:30:38] Final question, but I think I read that you were looking for funding and you did receive a chunk of it, is that correct?

Atticus: [00:30:45] We did, yeah. So we closed …

Eve: [00:30:48] Congratulations.

Atticus: [00:30:48] Thank you. Yeah. We closed on on our Series A round of financing a couple of weeks ago. So, we will be around for much longer.

Eve: [00:30:56] You’ll be bigger and doing more of this.

Atticus: [00:30:57] Hopefully. Yeah. We just keep putting one foot in front of the other and are anxious to expand to new markets that are interested in solutions.

Eve: [00:31:05] Well, it’s really been delightful talking to you and thank you very much, and thank you for tackling this very big problem.

Atticus: [00:31:12] Well, we’re trying. But thank you for having me, Eve. I really appreciate it.

Eve: [00:31:31] That was Atticus LeBlanc. He wants PadSplit to take hold in a really big way. He can’t see how we will ever be able to catch up and provide enough affordable housing quickly if we don’t think differently. That empty spare room or that basement den can offer a comfy bed and a safe home to someone who really needs it. So, he’s planning to grow the 1100 rooms on PadSplit today to many hundreds of thousands of rooms. PadSplit is his moonshot.

Eve: [00:32:15] You can find out more about impact real estate investing and access the show notes for today’s episode at my website, EvePicker.com. While you’re there, sign up for my newsletter to find out more about how to make money in real estate while building better cities. Thank you so much for spending your time with me today, Atticus. And thanks for sharing your thoughts. We’ll talk again soon. But for now, this is Eve Picker signing off to go make some change.

Image courtesy of Atticus LeBlanc, PadSplit