$1,000 and you’re a “Dome Construction Enthusiast”. Access to an exclusive virtual tour of the OCULIS Lodge construction site with detailed insights into dome construction AND a Q&A session with the project architects and builders to learn about dome-building techniques.

$2,500 and you’re a “Founding Member”. A group tour of the property and a private Q & A session with the founder and builders.

$5,000 and you’re a “VIP Explorer”. Two free nights in a dome (based on availability) with an early bird special along with VIP early booking privileges.

$20,000 and you’re an “Aspiring Builder”. Admission to a dome construction workshop, featuring hands-on training with experts, tailored for backers interested in building their own domes in the future with our technical support (travel costs not included).

Unusual and impactful lodging experiences in the great outdoors.

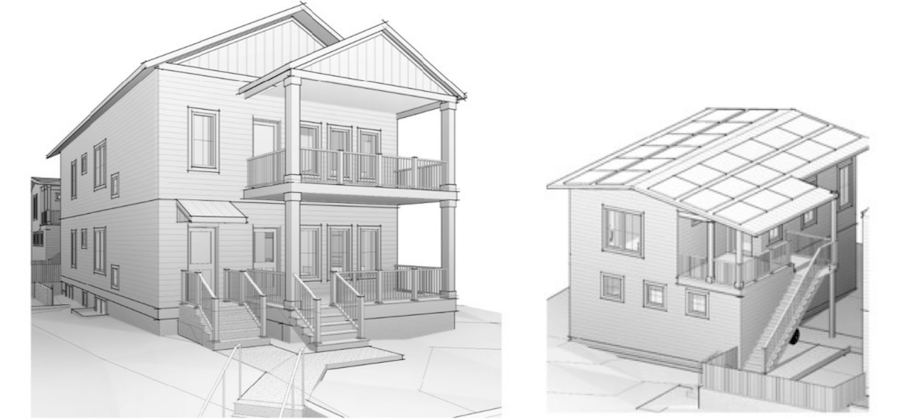

Oculis Domes envisions itself as a pioneer in redefining the lodging experience through a seamless blend of luxury, sustainability, and architectural innovation. Nestled in the stunning natural landscapes of Washington, their dome accommodations offer guests an immersive experience that combines the best of glamping, short-term rentals, and boutique hospitality. By offering architecturally distinctive stays, they cater to the growing demand for unique, memorable travel experiences that allow guests to connect deeply with their surroundings.

The developer is looking for investors small and big alike, just like you, on Small Change.

https://www.smallchange.co/projects/Oculis-Domes

This is not a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing is risky and involves the risk of total loss as well as liquidity risk. Past returns do not guarantee future returns. If you are interested in investing, please visit Small Change to obtain the relevant offering documents.

Image courtesy of Oculis Domes