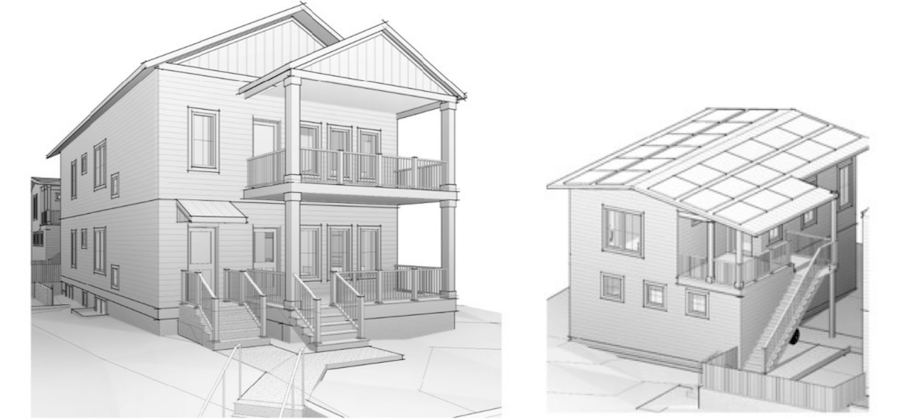

Missing Middle housing. 23 townhomes, duplex + 4-plex units

Affordable. Rents planned at 80% AMI

Additional phases. For a total of 67 units months construction period

Underway. Purchase + sale agreement executeduction commencement

Cost. $3.6M total project costing, dining and at least 3 parks

Deferred real estate taxes. Project awarded a 10-year PILOT, 75% deferral

Completion. Q1 2026 anticipated completion for Phase 1aces

A pocket neighborhood adjacent to Memphis Medical District.

Bellevue Montgomery is a multifamily project planned as an infill project in Midtown Memphis, Tennessee, adjacent to the Memphis Medical District. Even at the convergence of Downtown, Crosstown, and Midtown, the neighborhood does not have sufficient housing to fill the need for affordable housing. The Company intends to address this gap in the Medical District with much-needed “Missing Middle” housing. They’re looking for investors small and big alike, just like you, on Small Change.

https://www.smallchange.co/projects/bellevue-montgomery

This is not a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing is risky and involves the risk of total loss as well as liquidity risk. Past returns do not guarantee future returns. If you are interested in investing, please visit Small Change to obtain the relevant offering documents.

Image courtesy of Bellevue Montgomery