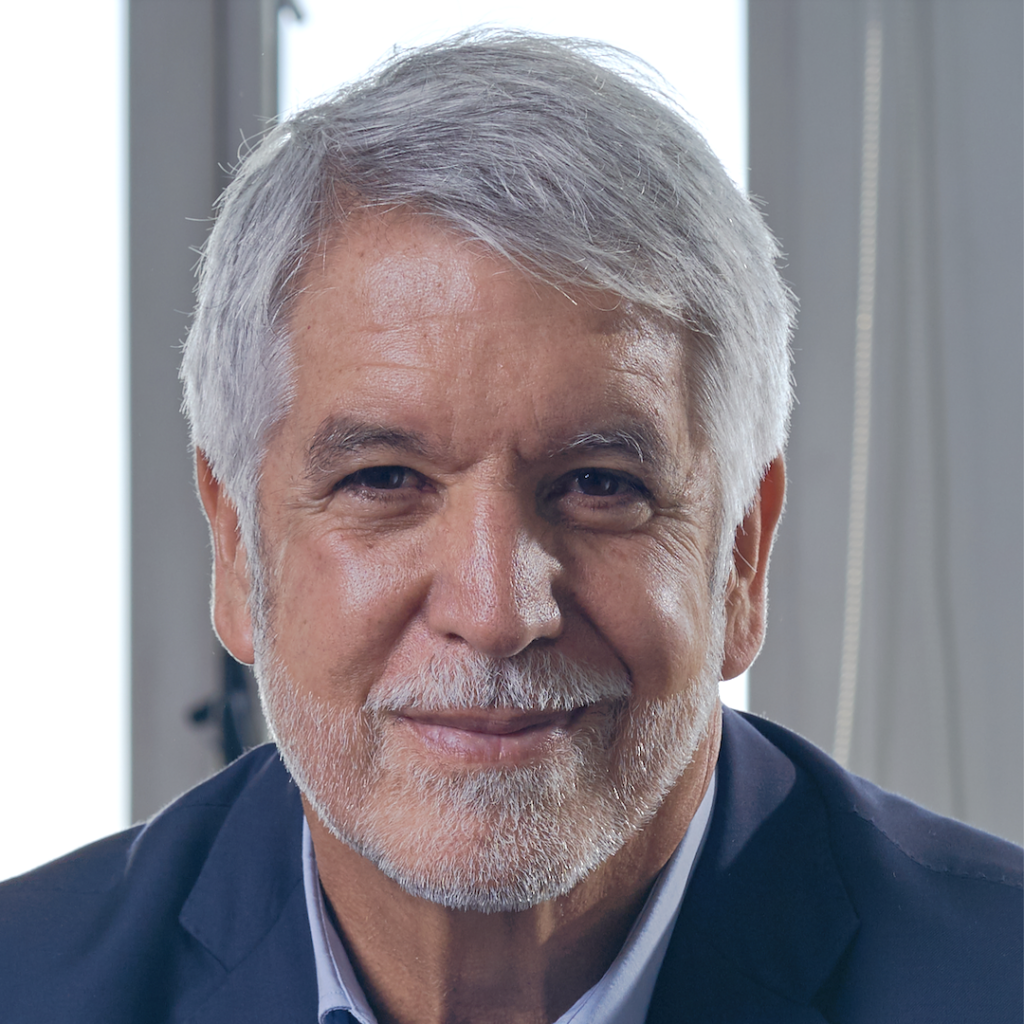

Enrique Penalosa is an internationally respected urban thinker, who, as Mayor of Bogota in two non-consecutive terms, profoundly transformed his city from one with neither bearings, nor self-esteem into an international model in several areas. As adviser and lecturer, he has influenced policies in many cities throughout the world.

Among his achievements is the creation of TransMilenio, the world’s best BRT (Bus based mass transit), which today moves 2.4 million passengers daily, inspired by the Curitiba model but much improved in capacity and speed, which has served as a model to hundreds of cities. Currently its lines are being extended by 61%. He contracted the first Metro line in Bogota which is under construction. He also created an extensive bicycle network when only a few northern European cities had one, greenways, hundreds of parks, formidable sports and cultural centers and large libraries, 67 schools, 35 of which managed by a successful private-public scheme and high quality urban development projects for more than 500,000 residents and a radical redevelopment of 33 hectares of the center of Bogota, previously controlled by drug dealers and crime which required demolishing more than 1200 buildings occupying 32 hectares, a few blocks from the heart of Colombia´s institutional heart, including the Presidential house.

His advisory work concentrates on urban mobility, quality of life, competitiveness, equity and the leadership required to turn visions into realities.

Penalosa has lectured in hundreds of cities and in many of the world´s most important universities. He has advised local and national governments in Asia, Africa, Australia, Latin America and the United States.

He is a member of the Advisory Board of AMALI (African Mayoral Leadership Initiative), Fellow of the Institute for Urban Research of the University of Pennsylvania. For over a decade he was President of the Board of New York´s ITDP (Institute for Transportation and Development Policy) of New York; member of the London School of Economics´ Cities Program Advisory Board. He was a member of the Commission for the Reinvention of Transport of the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority created by the New York Governor Cuomo.

His book Equality and the City was recently published by The University of Pennsylvania; in Spanish it was published Villegas Editores and in Portuguese by the IPP (Instituto Pereira Passos) of Rio de Janeiro.

Penalosa has been included in Planetizen´s list of The Most Influential Urbanists, Past and Present, the most recent time in July 2023. He was also one of ¨15 Thought Leaders in Sustainable City Development¨ selected by Identity Review July 2023. He has been awarded important international recognitions such as the Stockholm Challenge; the Gothenburg Sustainability Prize; the 2018 Edmund N. Bacon Award, the highest tribute of The Center for Design and Architecture of Philadelphia, given to him because of ¨the world-wide influence his pioneering initiatives have had on public transportation, infrastructure investment, and public space, including in cities such as Philadelphia and New York City¨. For Penalosa´s work Bogota was awarded the Golden Lion of the Venice Biennale.

Penalosa has a BA in Economics and History from Duke University, a Degree in Government from the IIAP (now fused with ENA) in France and a DESS in Public Administration from the University of Paris 2 Pantheon-Assas. He was Dean of Management at Externado University in Bogota and a Visiting Scholar at New York University.

Penalosa´s TED Talk has nearly one million views, his X account in Spanish has more than 2 million followers.

Read the podcast transcript here

Eve Picker: [00:00:13] Hi there. Thanks for joining me on Rethink Real Estate. For Good. I’m Eve Picker and I’m on a mission to make real estate work for everyone. I love real estate. Real estate makes places good or bad, rich, or poor, beautiful, or not. In this show, I’m interviewing the disruptors, those creative thinkers and doers that are shrugging off the status quo in order to build better for everyone.

Eve: [00:00:49] This is a long one, but I couldn’t help myself. Enrique Penalosa is an exuberant lover of cities, equitable cities. He served as mayor of Bogota, Colombia, not once but twice, profoundly transforming his city from one with no self-esteem into an international model. As mayor, Enrique launched TransMilenio, a bus mass transit system which today moves 2.4 million passengers daily. He also built an extensive bicycle network at a time when only a few northern European cities had one, along with greenways, hundreds of parks, sports and cultural centers, large libraries, 67 schools, and a radical 33-hectare redevelopment in the heart of Bogota previously controlled by drug dealers. This required demolishing more than 1200 buildings. Recently he published a new book called Equality and the City. Look for it on Amazon. Of course, the accolades are too numerous to mention here. Enrique’s work is considered significant and influential by many, and the list of awards is long. There’s a lot to learn here. More than an hour’s worth of podcasting can hold.

Eve: [00:02:21] Good morning. I’m really delighted to have you on my show, Enrique. I’ve been a huge fan of yours for a very long time.

Enrique Penalosa: [00:02:28] Thank you very much, Eve. Thank you. You’re really generous, and it’s a great pleasure to be with you.

Eve: [00:02:33] I know there have been many, many accolades. You’re one of the most influential urbanists, and you have a brand new book called Equality in the City. But I wanted to start with a question: why and how did cities come to take center stage in your professional life?

Enrique: [00:02:50] Oh, that’s an interesting question. I somehow talk about this in my book. I am from Colombia, and this, of course, conditions everything. My father was into public service, and he was the head of the Rural Land Reform Institute and the, and so I was as most middle, upper middle-class children in a developing country, in a private school. And I used to get beat up because they were this, institute was doing land reform, taking, forcefully buying land to distribute to small farmers. And so, since very early, I was obsessed with equality with, I was convinced that socialism was the solution, as many in my generation. It was that time around late 60s, 70s and I went to Duke University and there I really was very interested in studying all about this. And I realized socialism was a failure. It was both a failure for economic development, which for me was extremely important and sadly, also for constructing equality, because it was extremely hierarchical system with all kinds of privileges for the bureaucracy and all that. But at that time, when I was in college, my father became secretary general of the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements – Habitat in Vancouver. And he had always already been involved in in Bogota, he had been in city council, and at that time I began to be more and more interested in cities and less and less interested in the socialism, which I as I said, I realized it was a failure. And at that time my city was growing like 4% per year. Bogota. And I realized that maybe it was much more important to define the way cities would be built and even economic development, because economic development would come sooner or later, maybe 50 years later, 50 years earlier. But if cities were not done right, it was very difficult to correct them. If we were able to save land for a park as the city was growing or exploding, almost, this hectare or ten hectares or 100 hectares would make people happier for hundreds of years. Thousands.

Eve: [00:05:21] New York City is a really great example of that, with the fabulous park in the middle. That was very visionary. Yeah.

Enrique: [00:05:27] New York City, I mentioned this, and I work a lot with Africa recently, New York City created Central Park in 1860, when New York City had less than 1 million inhabitants and had an income per capita, very similar to some developing countries today. So, if we are able to save land for a park, it will make life happier for millions for hundreds of years. If we are not able to save land for that park and cities built over, it’s almost impossible to demolish, for example, the 300 hectares that Central Park has later. Demolish 300 hectares of city to create a park of that size. So I became more and more interested in cities. Obsessed. Later I did graduate school in Paris and, of course I was always very poor. When I was at Duke, I was on a soccer scholarship. And in Paris I worked a lot. I was a very low. I mean, I realized I was poor many years later because I was extremely happy. The city gave me everything I needed. And I realized how a great city can make life happy, even if you don’t have wealth or anything. I mean, it’s a, so I became obsessed with cities since then. When I majored in university, I studied economics and history and public administration and all that, but I never actually studied anything urban per se. But all my life that’s what I have worked on.

Eve: [00:07:02] Interesting. So, I have to ask you, what city do you think does that best today, makes people happy?

Enrique: [00:07:10] Oh.

Eve: [00:07:11] I wasn’t going to ask that question, but I have some of my own answers.

Enrique: [00:07:15] That’s an interesting city because I love all cities, you know, all of them have some charm and some great things. Clearly, today for everybody what is a great city is one that is good to be on foot for pedestrians. That’s the way. So, with that criteria, which city? What makes it a great city for pedestrians and for, also, I would add, a great city for the most vulnerable citizens, for the elderly, for the poor, for the children. And so the first thing has to have is great pedestrian qualities. And pedestrian quality means great sidewalks, of course, but also destinations, places to go to and people that you see in the sidewalks. We need to see people, to see people. I mean, we are pedestrians. We are walking animals. We need to walk to be happy. Just as birds need to fly or deer need to run, or fish need to swim. We need to walk not just to survive, but to be happy. We could survive inside an apartment all our life, but cities that are great for walking sometimes because they are very great sidewalks places such as I love New York, despite the fact that I think it’s a little too dirty recently.

Enrique: [00:08:35] And I think the occupations of public pedestrian space by by informal vendors really is getting out of hand. And this crazy, how is it that they put in the buildings the, andamios. Scaffolding all over the place that lasts for years. I mean, but despite that, I love New York because he’s so full of life and he’s so it’s so free and it has beautiful places like the riverfront and anyway I love, I mean I love all cities. And it seems very spontaneous, you know, spontaneous. So, it’s not like, and they are, everybody’s like doing their own thing and doing things. There are cities where you, I think you can be there and just simply lead a contemplative life. But others, if somehow brought you to do things, to do things, to be active, to create, to do, to do. Other cities, you can just, you know, go to the cafe, relax and that’s fine. But I like this energy New York has.

Eve: [00:09:45] You like active cities. Active cities, yeah.

Enrique: [00:09:47] Somehow brought you to be active and to create and to do things. But I mean, all cities are wonderful. I mean, all for different reasons. Mexico City, my city I like, of course. I mean, I love all cities.

Eve: [00:10:03] Yes. So, let’s move on. You had two terms as mayor of your city, Bogota, Colombia, and they’re often cited as transformative for the city. So, what led you to become mayor? I mean, I hear the love of cities, but becoming mayor is really another big step, right?

Enrique: [00:10:20] Yes. I was obsessed with the public service somehow. Always. This is why, even though it’s an interesting thing, I was born in the United States, because, but I was there for only one month, as my accent shows. When I was a kid, my family went back to when I was 15, to my father was working at the Inter-American development Bank and even though then, I was at Duke University, a very good university in the US, and I had a US nationality because I’ve been born there in one of these rare trips to Colombia, I renounced my US citizenship because, since then I was interested in politics. In politics and my father had been a public servant, but not elected. And he was attacked and all this and had many, and I remember always an uncle of mine who said, look, uh, your father was attacked so dirtily because he had neither money nor votes. So, I said I would not have money, but I will get votes. What gives you power when you are, and what makes you be able to do change when in government is to have votes. The difference between the one who is elected and the one who is appointed is like the difference between the owner of the company and the manager.

Enrique: [00:11:46] If you do, if you are appointed and you do anything that creates a conflict, you are fired. So, I always thought I wanted to be elected, and that’s why I said maybe to have a US nationality may become a handicap in the future. And I was obsessed with doing things for cities. More and more, the more I studied since I was in the middle of college, I was obsessed with studying and reading, and I lived in Paris, and I always dreamt of doing things that were very obvious. And I dreamt, for example, of bikeways much before, I mean, they were always bikeways in the Netherlands and Denmark, but there were no bikeways in Paris when I lived there, not one single bikeway. And in Bogota there were no sidewalks, very few almost. There was not one decent sidewalk in the city, in Colombia. And I always also dreamt that the rail systems were too expensive for our possibilities, that we needed to organize some kind of efficient bus-based mass transit. And, I mean, I was obsessed since then, and so I wanted to become mayor. I think I was a good mayor, relatively good. But I was not a good politician.

Eve: [00:12:58] We had a mayor like that in Pittsburgh. He was a fabulous mayor, but he was not a good politician.

Enrique: [00:13:03] Yes, yes, yes. I mean, I have lost like 7 elections in my life. And that sounds very quickly. When I said you, I lost seven elections. But in life, actually, it is almost one year of work every time, so like,

Eve: [00:13:14] Oh yeah.

Enrique: [00:13:14] You could say it’s lost seven, seven years of life for elections that were not successful. But to make the story short, in my life, I was, after a big effort, I was elected, but I wanted to be mayor because I wanted to do things. I had a whole vision in my mind of what I wanted to do. I did not want to be mayor, but to do as mayor.

Eve: [00:13:43] Yes, I get it. I mean, I’ve read that even the way you became elected, you didn’t really rely on a party machine. You relied on meeting with people one at a time, right? It was all about connecting with the people.

Enrique: [00:13:55] That’s right. Eve. When I started, Colombian politics was only machinery, very powerful machineries, organizations and a lot of money distributed to local leaders. And I did something that was completely new at that time. It’s very obvious. And I had nothing creative now in the world. It’s very easy to start to distribute little leaflets in the street, which nobody had done at that time. Even I did some interesting things that were different. For example, the first politician had a smiling picture. At that time, all of the pictures were more like, great…

Eve: [00:14:34] Powerful. Yes.

Enrique: [00:14:35] And I also put a resume and anyway, so I was able and going to homes one by one. Anyway, I was elected. I was able to be elected first to Congress, like this. And a few years later to mayor with no party, as an independent really.

Eve: [00:14:57] Independent. Interesting. So, describe Bogota as a city when you took office and some of the challenges you faced.

Enrique: [00:15:06] That’s interesting because Bogota, as most developing cities, well, Bogota, our cities have lacked a lot of planning. And even when they did plans, they weren’t very nice plans. Architects draw and they don’t, are not implemented. So a few things were a few roads, a few main big roads. But for example, more than 40% of Bogota when I was first elected in ’97, had informal origin, had been of informal origin. And since I had worked in the past in things with the city, for example, I was Vice President of this Bogota water company. I had really worked closely, and I knew very well, and I was very obsessed with this informal organization, how lower income people were not able to get legal land, well-located legal land. So were they forced to the steep hills around the city, steep mountains, or flooding zones near the river and so with the water company we used to we’re able to work a lot in the legalization of this to bring water and sewage. And so, this is one thing Bogota had. Another thing Bogota did not have sidewalks, practically not one. I would say they were not one. They had been a few decades before a few sidewalks built or some sidewalks, but the cars simply were parking on top of them whenever they had been built. And and many places they had not even been built at all. So, it was horrible for pedestrians and of course Colombia has always been a very much of a bicycling country. It’s the only developing country, the country in the developing world that has successful cyclists at the world level. Some Colombians have won.

Eve: [00:17:00] That’s interesting. Yeah.

Enrique: [00:17:02] There is no other developing country in the world. I mean, you would think this is not an expensive sport. It’s not like yachting, but nevertheless, for some reason, Colombia is the only developing country that is successful. For example, Colombian won the tour de France and Colombians have won the tour of Spain and of Italy.

Eve: [00:17:22] Oh wow! I didn’t know that. Yeah.

Enrique: [00:17:25] But there were no bicycling for work. For zero for transportation. It was like a sports thing. And of course, only 10% of the people have cars, but they were the richest and most powerful people in the city, and they think they could park in the sidewalks or two. And they thought the bicyclists were a nuisance if there were any. They were nobody used to go to work by bicycle. There were almost no parks, and the few parks were completely abandoned and not in a good shape. So, this is the environment I found, more or less. And of course, the traffic jams were worse and worse, and there was not a decent public transportation system. Of course, there was not a metro and there was not a, the bus system was completely chaotic. There were thousands and thousands of buses that were almost individually owned, racing against each other, people hanging from the doors. And sometimes since they were fighting for passengers, they would block the another ones and the other bus the driver would get out with a cudgel and break the windows of the other bus. Even if the other bus was full of passengers, it was like the Wild West. And that’s the city.

Eve: [00:18:45] It was. It was like the wild… Just just backing up a little bit, how many people live in Bogota?

Enrique: [00:18:51] Now we have like 8 million inhabitants in Bogota.

Eve: [00:18:55] It’s a big city. OK.

Enrique: [00:18:56] And also in the surrounding municipalities, like a little bit about a million, 200 more or something like that.

Eve: [00:19:02] Okay, okay. And then it was also a lot of poverty and drug activity and altogether not a very healthy city by the sounds of it.

Enrique: [00:19:12] There was a lot of poverty because we were a developing city that was very poor. And we are still I mean, so far, for example, Colombians income per capita today is around $6,000. And the United States income per capita is like $80,000 or something like that. So it would take us if we do very well with very high economic growth rates, it would take us maybe, even if we have very high economic growth rates, like, for example, if we if we grow at 3 or 4% per capita annually, it would take us more than 150 years to reach today’s income per capita of the United States, not to catch up to the United States, but to reach where the United States is today.

Eve: [00:19:53] Wow!

Enrique: [00:19:54] We have advanced a lot. Colombia has progressed a lot and we have reduced poverty very much. We have made huge advances in education and all that, but we are still at poverty. But of course, we had much more poverty 25 years ago when I first became mayor.

Eve: [00:20:10] So what did you tackle first?

Enrique: [00:20:13] One thing before I go into that, I’d like to say that this experience in urbanization, urbanization is fascinating because it’s gigantic. I mean, when I became mayor, Bogota’s population would double every 16 years or so, and the size of the city grows much more than proportional to population, because as a society gets richer, there are more buildings that are different from housing. For example, when a society is very poor, barely there are housing buildings. As societies get richer, there are shops, there are factories, there are offices, there are universities. And one thing that is very interesting, this is not just history. What we are talking about is not history because this is the challenge in Africa. I think the most important challenge in the world today is African urbanization. Today in Africa, there are more than, in sub-Saharan Africa, there are more than 250 million people who live in slums. Horrible poverty, slums with no electricity, no water, no sewage. Different degrees of poverty, but all of them horrible. And if these things continue the way as they are, they would have more than 500 million more people living in slums in 20 years. African urban population, it grows by the amount of the US population, about 320 million or something, every 15 years or so. So every 15 years, Africa has to build the amount of housing that the whole US has today every 15 or 16 years, you know. And they are extremely poor, not only housing the sewage, the water…

Speaker4: [00:22:03] The infrastructure.

Enrique: [00:22:04] The schools, the roads, they’re going to have giant cities, cities that maybe like Lagos, cities that maybe 60 million inhabitants or more. So, it is extremely important not only for Africa but for the world to do good cities in Africa. Even if at first they do not have all the water or sewage, but to leave enough space for roads, for parks, for public transport, because otherwise this is going to be horrible for the environment and horrible suffering for people. And this is even a problem for the security of the world, because this is going to be a completely inhuman situation that can have unexpected consequences. So, what I’m saying is that my experience in Latin America is some, a few decades ahead of Africa in economic development and urbanization but this is still a big challenge for the world. This is not just history.

Eve: [00:23:10] I suppose I’m wondering how you convince people. Because Bogota Ciclovia is a really amazing, iconic symbol of the city. I understand that now every Sunday, 75 miles of roads are shut down and given over to people to enjoy, almost like a Millennial Park, right?

Enrique: [00:23:30] Exactly. This is a beautiful thing that we have in Colombia.

Eve: [00:23:35] So I actually was so inspired by this, I co-founded an open street in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and I can’t tell you how hard it was to get one mile of it because everyone complained about, you know, the street in front of their shop that someone couldn’t park there and shop there that day. It was exhausting because people don’t understand the potential that that has. And I don’t know how you get to 75 miles, like, this is huge! You know, how do you convince people that they have to be fabulous cities in Africa or we’re all going to suffer? It’s, most people don’t want to think about it.

Enrique: [00:24:20] Yes. There are several aspects of this. This is a fascinating thing. It all has to do with equality, which is the theme of my book in a certain way, how cities can construct equity so that a good city is one place where nobody should feel inferior or excluded. A good city is also one where, if all citizens are equal, then public good prevails over private interest, you know? So, in developing countries, in Africa or even in Colombia and most, almost there is not one single developing country where more than 50% of the people have cars. Always developing country, almost by definition, I would say, is that it’s a developing city is one where less than 50% of the people have cars. And the one thing we should remember is that if we are all equal, as all democracies say, all constitutions state that all citizens are equal, then a citizen on a $100 bicycle is equally important to one on $100,000 car. And they have, or a citizen that is walking or is on a bicycle has a right to the same amount of road space that a citizen that has goes in a luxury car. The same amount. There is, the person in the car usually think they have a right to more space than the people in the bicycle or so, and they honk at the people in the bicycle.

Eve: [00:25:53] Oh yeah.

Enrique: [00:25:56] So, so this is very beautiful, what we have achieved in in Bogota because,I mean, it was created before, but it has been expanding, actually, when my brother was the head of the Sports and Parks and Recreation with another mayor, he expanded a lot and I expanded it a lot. So, we get, on a sunny day, we may get, a million and a half people out in the street. And one thing that is important is that Bogota is a very compact city, very dense. We have more than 220 inhabitants per hectare. So, it’s a beautiful ritual of human beings reconquering this city for themselves. One thing that I did that is interesting too, is that I held a referendum for people to vote, and one day a year a work weekday, we have a car free day. So, this whole 8 million inhabitant city has no cars, no cars at all, during the whole day. Everybody has to use public transport or bicycles. We have taxis but no private cars. And so, it’s an interesting exercise, not only in terms of the environment or even mobility, but of social integration. One of the most crucial things that we need, especially in unequal, in more unequal societies like ours, is that all citizens should meet as equals. For example, someone who owns an apartment in Fifth Avenue in front of Central Park in New York.

Enrique: [00:27:38] He may meet the doorman of the building, but they meet separated by hierarchies. One is the owner of the apartment, and the other one is the employee, low paid employee. But if they meet in the sidewalk or if they meet in the park, they meet in a completely different way. They meet as equals or if they meet in public transport. So, in a great city, people meet as equals. This is not enough for, but this is one of the kinds of equality that a good city can construct. And so in these kind of exercises, if we get people to meet together, for example, if two people meet in bicycles in a traffic light, maybe one bicycle is a $10,000 and the other one is $100, but it doesn’t matter. They both meet as fragile humans, vulnerable. They see each other. They have the same right to the street. They have the same right to the space. It’s very different than if somebody is in a crowded public transport, and the other one is in a luxury car or something. In this there is a proximity, there is a vulnerability. And so, these exercises that we do in Bogota, I think they are interesting. And they are good for the environment, they are good for mobility, and they are good for social integration or construction of some kind of unconscious equity.

Eve: [00:29:11] So you as mayor, you focused on mobility, not just bicycles, right? I read about the TransMilenio, the first metro line, a huge bicycle network, greenways. Do you want to tell us a little about all of that?

Enrique: [00:29:26] Thank you very much, Eve. Yes. For example, the TransMilenio, the BRT. I have even written about how we should organize a bus system that was different than the one I described earlier, with exclusive lanes for buses and a system that, where people would have prepaid cards so they would not take time to board the bus. And then I found the Curitiba system. Mayor Jaime Lerner in Curitiba had done a wonderful, in Brazil, Curitiba had done a wonderful system. But Curitiba was a small city. The system had been created like in 1973 or 4. And they only had 500,000 inhabitants, at that time. It did not have much impact. But then to me, I marvelled because I said, this is the solution. This is perfect because rail systems are too expensive. I mean, subways are wonderful. But they cost a huge amount of money. It’s extremely expensive to build an extremely expensive to operate. And so, we created a BRT system and actually we were innovative even in that we gave a name to it. You know, one of the things that I, I knew from, since you tell me you are in Pittsburgh, one of the first places in the world where they did some exclusive lanes for buses was Pittsburgh.

Eve: [00:30:50] Oh yeah. I use it. I used it a couple of times a week. I live downtown, and I have an office in East Liberty, a building in East Liberty, and it takes me seven minutes on the busway. And if I drive, it’s 30 minutes.

Enrique: [00:31:03] Exactly. You know, so…

Eve: [00:31:05] It’s Fantastic. Fantastic.

Enrique: [00:31:07] Well, I’m very happy that you say that, because I like to tell you and to tell the Pittsburgh people that one of the things that influenced me to create TransMilenio was the Pittsburgh project, because that’s before TransMilenio. I found about it. And these things motivated me and inspired me.

Eve: [00:31:23] It’s very limited. I wish they would expand it. They’re doing a line now from downtown to Oakland, which is the University Center, but they’ve been talking about it for 30 years, you know, takes a very long time to do things.

Enrique: [00:31:38] This brings us to the fact that solutions to mobility, more than an issue of money, are an issue of equity and political decision. This is very obvious. Some things, sometimes for us, they are before our noses, and we don’t see them. You know, for example, only about 100 years ago or a little bit more, women could not vote, you know, and it was not fascist who thought women should not vote. I mean, normal people, good people thought that this was good. That was normal, you know? And today we see this is completely mad. Or how about only about 70 years ago or so that, even in the United States that the African Americans had to give their seat to the whites or things like this, that today we think is is mad. But at that time, I’m sure many people who were good people thought this was normal. And so, in the same time, sometimes inequalities before our noses, for example, I believe it’s completely crazy that we have a bus with 50 people and then you have the give the same space that you give to a car with one, you know. This is not democratic. Besides, it’s not technically intelligent because actually a BRT is the most efficient way to use scarce road space. Since we are going to have buses, a BRT is the way that you use the least energy, the way that you use the least amount of buses, the way that you use the least amount of road space. Anyway, we created TransMilenio, which became a model to hundreds of cities around the world. It’s a system that has an amazing capacity. It moves more people per kilometer hour anyway you want to measure it than almost all subways in the world.

Eve: [00:33:28] Wow.

Enrique: [00:33:28] We move more people, passengers, our direction and also within Europe. There is only one line in New York subway that moves more than us and that’s the Green Line. But that’s only because it’s two lines actually: the express line and the local one.

Eve: [00:33:43] Right.

Enrique: [00:33:44] But our system moves more passengers per kilometer than practically even all the New York subway lines. And of course, it costs 15 times less. And this is, I think, you need more of this in many cities in the US, it’s the only way to be able to give this kind of service, even to suburbs, because this can have more flexibility. Anyway, we created this, this system. It has 114km today. And it moves a 2.4 million passengers per day.

Eve: [00:34:14] Wow.

Enrique: [00:34:15] And it’s being expanded by 60%. Now, at this time. So, we should reach easily more than 3.2 million passengers per day or something like this. And now, of course, most buses are bi-articulated buses with gas fuel. But soon all of them will be electric, of course, as well. So, and I’m sure very soon in ten years or so, they will also be driverless. So actually, what makes a mass transit system is not the fact that it has metal wheels or rubber wheels, but the fact that it has exclusive right-of-way. That’s what creates the the mass transit, the capacity, the speed. We don’t have time to go into these boring technical details. But what is interesting also is the democratic symbol it represents, because I have seen everybody in the world wants subways.

Eve: [00:35:14] Yes.

Enrique: [00:35:14] Upper income people all over the world, subways, preferably underground. So, they don’t even have to see the low income people that go in them. You know, in developing countries, I mean, this is not the case in London or in Paris or in New York, but in developing countries, all upper income people want subways, but they have not the slightest intention of using them. It has not crossed their mind. You know, I am sure that if you have Mexican friends, that are most likely upper middle-class citizens, 99% of the cases, not only they don’t use this, I mean, the Mexico City subway is one of the most extensive networks in any developing city in the world. I think only Delhi and maybe another one has longer one. But the upper middle class or upper class even less, it’s not that they don’t use it, it’s that they have never even been to it once in their lifetime. Never.

Eve: [00:36:14] So, you know that’s not only true of them. I have a Pittsburgh born and bred friend who’s in his 50s who has never ridden a bus. Ever. I was completely shocked when he told me that.

Enrique: [00:36:27] There is something very interesting. Transport has a lot to do with status for some interesting reason. You know, this is why some people pay $500,000 for a car, which basically that’s something very similar to a $50,000 car, you know, but then it’s very cool. The fancy car. And for example, in 1940, there were trams in every city in the world with more than 100,000 inhabitants. But at that time, trams were identified with the poor, with the lower income people. They were jammed and so, buses appeared. For some interesting reason buses appear much later than cars, because at first, they were not the technologies for pneumatic tires, and the only until 1920, or even more, most streets in the world were cobblestones. So, a solid rubber tire, big vehicle on cobblestones, of course, would fall apart in a few blocks.

Eve: [00:37:27] Yes.

Enrique: [00:37:28] Jumping.

Eve: [00:37:29] Yeah.

Enrique: [00:37:30] And so buses appeared, and in 1940 buses were sexy. They were the sexy, the modern thing. And trams were identified with something for the poor. Now it’s the opposite. Now, in the US, buses are identified with the poor, with the Latin Americans, with the African Americans. And the cool thing is trams. So, everybody wants to put trams, trams. All cities think trams will revitalize the city centers and all that. And, of course, trams are nice, but basically, they do the same or less than buses and they cost a lot more. But they are sexy, you know, and so we have to make bus-based systems sexy to finish this story. We may have $100,000 car stuck in a traffic jam, and there are many traffic jams in Bogota, and the bus zooms by next to it. And even a little boy can’t make faces to the guy in the car, you know, and say, hey, they can go, you know?

Eve: [00:38:31] Yes.

Enrique: [00:38:32] So it’s a symbol of democracy in action, a BRT when the expensive cars. So, because, even if an underground subway is wonderful, it’s not as powerful symbolically as the bus that zooms next to the car, because it shows that public good prevails over private interest. Democracy is not just the fact that people vote. Democracy it also requires that if all citizens are equal, public good prevails over private interest. And this is the essence of the busway. And also, this is the essence of bikeways. When first we started to do bikeways in Bogota, when I first became mayor, we did like 250km of protected bikeway, the first time I was mayor. When there were no protected bikeways anywhere in the world except the Netherlands and Denmark and a few in Germany. There was not a meter in Paris or in New York, or in London. Maybe there were a few kilometers somewhere in California or something. But we created this network and again, it’s the equity principle is what is behind it. What we are saying is a citizen on a $100 bicycle is equally important to one on a $200,000 car. And the protected bikeway not only protects the cyclist, but it raises the social status of the cyclist. And this is very interesting. Bogota today has the highest amount of cyclists in any city in America. Amsterdam has a much higher percentage, of course, but since we are much bigger, we have more cyclists than Amsterdam.

Eve: [00:40:12] Interesting.

Enrique: [00:40:13] We have like a like a million people every day using bicycles.

Eve: [00:40:17] Your optimism about this is infectious, but I can’t wonder what sort of pushback you had because wealth is powerful, right? So even if 10% of the population don’t get it, that must have been an enormous lift.

Enrique: [00:40:32] I had a lot of enemies in politics. Yes. I mentioned I was not a good politician. Amazingly enough, I was re-elected in Bogota. There is no immediate re-election. If I had immediate re-election, I would have loved to have 2 or 3 periods. I really would have transformed Bogota. But I had to wait several years afterwards. And it was very difficult, even, for example, when I was just having the war to get cars off the sidewalks and to put bollards, for example, they made this huge calumny. Half of Colombians thinks that I made a business making bollards, you know? And there was never an investigation. There was never even a press article. Nothing. But there was so much calumny that I would say, if we make a poll, a half of, not Bogota people, Colombian people, think I made some kind of business from making bollards, or that my mother had a bollard factory or my brothers or something. Because we had to put bollards because we built a lot of sidewalks. But we did not have enough money to build the sidewalks everywhere. So we had to put bollards where we did not have money to build sidewalks. It’s always difficult. I try to do many things. I mean, again, we have to do what will improve the life of all and this implies conflicts. For example, now I talk very quickly about how we create the TransMilenio. But these people who used to have individually owned buses before TransMilenio, they were extremely powerful, extremely well-organized, and they would bring the city to a halt on a strike, and they would put the president on his knees. When I was doing TransMilenio, the President would call me once they had a strike, and he would call me all the time at home and everything to tell me to stop and to negotiate, that this was not tolerable.

Enrique: [00:42:30] Happily, in the Colombian constitution, the mayor has a lot of autonomy, and I did not have to obey the President. But I don’t say this is the kind of difficulties that you find when you are seeking the public good. And not only that, for example, many of these traditional bus operators became the contractors of the TransMilenio system, and actually it was very good business for them. But it was not easy. And, for example, there was the most exclusive club. This is the cover of my book, by the way, the cover of my book. The most exclusive country club in Colombia where the elite of the elite, maybe, I don’t know, 1500 members, the all the former President, the richest people in Colombia, I mean the most powerful people. I use eminent domain to turn the riding stables and the polo fields into a public park. And I also said that the whole golf course should become a public park as well. And this was, of course, very difficult. And, of course, all of these are battles. Battles, battles. Sometimes I have to battle the drug traffickers who control the whole area downtown. The police would not enter this area unless they were on a big operative with a hundred police, but five police would not go there because it was completely controlled by crime. And this was two blocks from the Presidential palace, from the main square in the country, in the city, from Congress, from the Supreme Court of Justice. And it was extremely difficult. And there we demolished more than 1200 buildings in my two terms and were able to create parks and housing.

Eve: [00:44:16] Wow!

Enrique: [00:44:17] But everything that you do is difficult. It’s difficult and painful.

Eve: [00:44:21] And yet you went back for a second time.

Enrique: [00:44:23] I went back, this, yeah, this thing that I just.

Eve: [00:44:25] Is there a the third one that we need to know about?

Enrique: [00:44:28] Well, I was feeling that I was already in a certain age. But then, once I see Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump as candidates, so I feel very young again.

Eve: [00:44:41] Very good. It’s only a number, right?

Enrique: [00:44:43] So I will go for another time or something.

Eve: [00:44:48] This is an amazing story. So, I want to ask you what’s the accomplishment you are most proud of?

Enrique: [00:44:54] Well, there are many things that made me extremely happy. For example, I was able to get more land for parks than all the mayors in the city in the whole history. The TransMilenio is very exciting to me because I think, again, as mobility, as symbol of democracy. There are some other things that we did that are very beautiful. For example, one of the most difficult things is to give good education to the poorest people, quality education. And we began to build some beautiful libraries, like four large, beautiful libraries, some in low-income areas. So, they are symbols that construct, like temples, that construct values, that knowledge and education are important. But also, we created beautiful schools. Beautiful, like the best private schools of the upper income people in the lowest income neighborhoods and former slums. And these beautiful, but more important than the building is that we created a system that has cost me blood politically, because I confronted the extremely powerful teacher’s union in which we said, we are going to get the best private schools and the best private university to manage these public schools in the poorest areas.

Speaker4: [00:46:09] And we have now 35 of these schools that we built, and we are able to contract with this, the best university. And the results have been amazing. Amazing. It’s really amazing that these children with the poorest people, because these schools are all in the poor, they are not in middle class areas, they are in the poorest neighborhoods. These children have academic results that are comparable to the upper income children in private schools. And of course, this has been extremely exciting. I mean, I will tell you that 99% of these children who study, they’re already graduates, or they have no idea that I, that I did this. But the teacher’s union has it very clear and it has caused me blood because they have been specialists in calumny me and to say all kinds of lies. And of course, the fact is not that all public schools are going to be managed in this way, but this creates a competition with…

Eve: [00:47:09] Equality, yeah.

Enrique: [00:47:10] Exactly, a model. So, we have to understand why these children in these schools, why these schools work so much better, so much, amazingly much better than the other public school that is managed by the traditional public union style only a few blocks away. And it’s not only in academic results that are amazing in the S.A.T. kind of things, but also, for example, much lower drug consumption, much lower desertion. I mean, when desertion rates that these children leave schools. Much lower gangs, even the whole neighborhoods crime goes down.

Eve: [00:47:50] Interesting.

Enrique: [00:47:51] It’s really fascinating. And of course, like many things that, so this, if you say, what are you most proud of? I think that these schools are teaching some things which have not yet been adopted by the rest of the educational system, but it’s very clear what it is that makes them much better.

Eve: [00:48:08] Interesting. We could talk all day, but I’m going to have to wrap up. So one more question. What’s next for you?

Enrique: [00:48:17] Well, we have in Colombia this time what I consider a terrible national government. We’re doing many crazy things, and I continue participating in politics. I mean, I have, like more than 2 million followers in Twitter, and so I try to give opinions or things. I may run for office somehow, even if it’s just to help somebody in the end, somebody else. I’m not obsessed with power, but I will try to contribute, and I’m also working very much internationally. I am very, I have been given the opportunity by some programs in Africa that are being, built by AMALI, an organization called AMALI and by Bloomberg. So, I am extremely interested in being able to participate more in African organization. I think this is a huge challenge, not just because we could avoid horrible problems, but because we could do cities that are better than anything that has been done before in the world. For example, in Africa, one of the things that we did here that I’m most happy about, we did more than 100km of greenways crisscrossing or bicycle highways crisscrossing an extremely dense city, because this is easy in a suburb, maybe, but this is extremely difficult.

Enrique: [00:49:33] And so, African cities could very easily have thousands of kilometers of greenways crisscrossing them in all directions. Imagine, not just one central park, but some parks all over the place. I mean, African cities can profit from the experience of all cities in the past, and in many cases, it makes it easier. In many cases, land is owned not by private owners, land that runs it by tribes or by national governments. So this is something that I hope that I’m able to participate more, because I think African people are wonderful, and I think there is a fantastic possibility to profit from us. I tell them, look, it’s not that I want to teach you the wonderful things we did. I want to tell you all the wrong things that we did, that you can avoid. Because our process of urbanization is so recent. I say, oh my God, if we had done this, that, that, that, that we would have we could have avoided so many mistakes.

Eve: [00:50:35] Yeah. Well, this has been just an incredibly delightful hour. I could go on forever. And of course, now Bogota is on my bucket list. I have to go there. Especially on a Sunday. I can get to ride those 75 miles. It would be amazing. So, thank you very, very much for joining me. And I hope every city gets your touch.

Enrique: [00:51:02] Thank you very, very much for the invitation. Thank you very much.

Eve: [00:51:19] I hope you enjoyed today’s guest and our deep dive. You can find out more about this episode or others you might have missed on the show notes page at RethinkRealEstateforGood.co. There’s lots to listen to there. Please support this podcast and all the great work my guests do by sharing it with others, posting about it on social media, or leaving a rating and a review. To catch all the latest from me, you can follow me on LinkedIn. Even better, if you’re ready to dabble in some impact investing, head on over to smallchange.co where I spend most of my time. A special thanks to David Allardice for his excellent editing of this podcast and original music. And a big thanks to you for spending your time with me today. We’ll talk again soon. But for now, this is Eve Picker signing off to go make some change.

Image courtesy of Enrique Penalosa