“As part of my series about “individuals and organizations making an important social impact”, I had the pleasure of interviewing Eve Picker” writes Yitzi Weiner for Authority Magazine.

“Eve Picker is the founder and president of Small Change, a crowdfunding platform that enables developers to raise capital for real estate projects with social impact. She is a trained architect with extensive experience in urban planning, real estate development, and community building. Under her leadership, Small Change, which was founded in 2016, has helped 39 developers raise over $10 million for projects in 21 cities, big and small, across the United States.”

Want to read the entire interview? Click here!

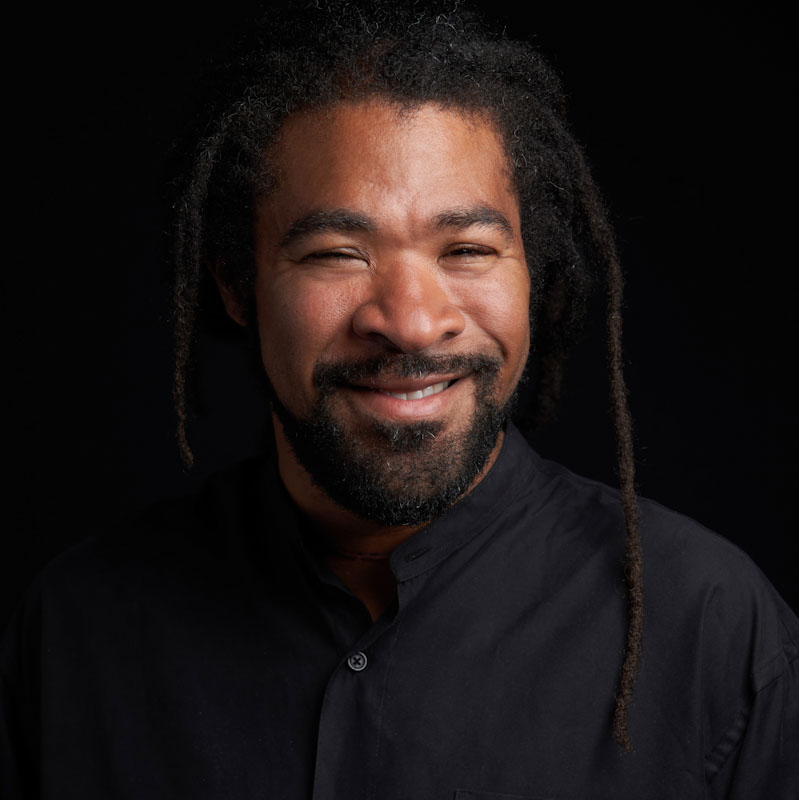

Image courtesy of Eve Picker