Joseph Minicozzi is an urban designer who wants to help communities understand the economic impact of development. Like demystifying tax codes, government jargon and municipal finance data.

In 2012, Joe created a data-focused consulting company called Urban3. Based in Western North Carolina, Urban3 was spun out of Public Interest Projects, a non-profit focused on reinvigorating downtown Asheville. For over a decade Joe had worked there as New Projects Director, including a two-year stint as executive director of the Asheville Downtown Association.

Urban3 embraces data and GIS mapping to highlight land value economics, property and retail tax analysis while wedding that to community design. While they have a vested interest in Asheville, Urban3 has consulted for cities both in the U.S. and abroad.

Previous to U3 and Public Interest Projects, Joe was a founding member of the Asheville Design Center, a non-profit community design center. He also worked as independent consultant on urban design and planning issues for many years, before which he was the primary administrator of the Form-Based Code for downtown West Palm Beach.

Joe holds a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Miami and a Master of Architecture and Urban Design from Harvard University. In 2017, Joe was recognized as one of the 100 Most Influential Urbanists of all time.

Read the podcast transcript here

Eve Picker: [00:00:08] Hi there. Thanks for joining me on Re-Think Real Estate for good. I’m Eve Picker and I’m on a mission to make real estate work for everyone. I love real estate. Real estate makes places good or bad. Rich or poor, beautiful or not. In this show, I’m interviewing the disruptors, those creative thinkers and doers that are shrugging off the status quo in order to build better for everyone. If you haven’t already, check out all of my podcasts at our website. Rethinkrealestateforgood.co. Or you can find them at your favorite podcast station. You’ll find lots worth listening to, I’m sure.

Eve: [00:00:58] Joe Minicozzi has been recognized as one of the 100 most influential urbanists of all time. Although he trained as an architect and urban designer, that honour was not bestowed for designing buildings or places. Joe’s influence comes through data. Joe helps communities understand the economic impact of development. He does this by tracking data in the built environment. Demystifying tax codes, government jargon and municipal finance. Stuff that most developers and governmental entities don’t think about when planning their next development project. Joe’s deep dives have uncovered some astounding and important truths about the cities we live in. I’m fascinated by his work and findings, and I’m sure you will be too.

Eve: [00:01:50] If you’d like to join me in my quest to rethink real estate, there are two simple things you can do. Share this podcast and go to Rethinkrealestateforgood.co, where you can subscribe to be the first to hear about my podcasts, blog posts and other goodies.

Eve: [00:02:12] Good morning, Joe. I’m really delighted to have you on my show today.

Joe Minicozzi: [00:02:15] Thank you for having me. I’m glad to be here.

Eve: [00:02:18] So,I trolled your website a little and I found a really, which is actually a really interesting name. Your business Urban3. I found a really interesting quote that I want to understand. Don’t fly blind. Visualize and reshape your economic reality with Urban3. What does that mean?

Joe: [00:02:39] Well, the visualizations and visualizing your reality is, basically we use Esri software. GIS software to make maps of cities to reflect their economic position. What’s going on from a cash flow standpoint and what you find in that, is different building types actually produce more wealth than other building types. Or once you see the picture, it helps people realize that there’s policies that are actually affecting cash flow. And the name Urban3 is kind of a funny thing that we did that originally was supposed to be Urban Cubed because the three-dimensional environment is cubic. It’s the 3D world. You and I are both urban designers. So, I wanted to kind of play on urban design in the name. But the IRS wouldn’t accept the cube is a part of our name, and they dropped it to the 3 after the name, So,they were stuck with it. So,that’s where we’re at.

Eve: [00:03:40] They don’t accept the at the beginning too, you know? Yeah. Very strict rules.

Joe: [00:03:45] Very big rules. Yeah.

Eve: [00:03:47] Yeah. So, OK, So,you’re visualizing the three-dimensional shape of cities to determine the economic reality of the cities?

Joe: [00:04:01] Sure. Or to think of it is, you know, for the real estate developer folks on this podcast, you’re playing with the cash flow, right? Things cost money and you have to pay for them. You have to make money on rent to pay for the building. And it’s really simple cash flow and you need to make more money than it costs or else you’d be out of business. You wouldn’t be a real estate developer or even in business as a person, you know, I can’t sell donuts at a loss, you know? So,cities are the same thing. Cities are really big real estate development projects and counties more so. Counties are are fixed. You can’t annex the next county over. So,when you have a city, it’s got a cost of roads, the cost of pipes, the cost of infrastructure, infrastructure that real estate wouldn’t be worth anything until somebody ran a pipe and a road to it. So, the question I ask is, are you paying enough taxes to cover the cost of that expense? And what we demonstrate with these models is we show it. We show how financially subsidized certain development patterns are.

Eve: [00:05:03] And So,and how do you create these models?

Joe: [00:05:07] That’s math and fancy software. It’s a geographic software, So,it’s got networks within it. You know and cities already have the data. That’s the thing that’s kind of crazy. They alSo,have the software. We’re just we’re just innovating the use of the software.

Eve: [00:05:25] So,for people listening, I’m sure they’ve seen spiky charts which show huge spikes of activity in urban areas. And so, it’s kind of like 3D charting of data.

Joe: [00:05:38] Exactly.

Eve: [00:05:39] Okay.

Joe: [00:05:40] Or do you think, there’s for more people who are into, I guess you call it BIM in the architecture world, or they are doing feedback systems of HVAC and all this stuff, and you’re starting to see way more sophistication on running your thermostat differently and particularly in green technologies. This is taking that same type of technology but applying it at a macro level across the city.

Eve: [00:06:03] So,we’re living in a data driven world and you’re applying data to helping cities become healthier economically.

Joe: [00:06:13] That and getting people to realize the consequences and costs of sprawl. So, we’re not going to change sprawl habits until people are aware of the true destruction that it causes and the defense of people that live in that, who wouldn’t take the deal when a house is a single family detached house in Eugene, Oregon, is subsidized to the tune of 1,400 dollars an acre. You know, it’s like…

Eve: [00:06:35] Right.

Joe: [00:06:35] You’d be stupid not to take that deal. So, if we want to see it, if we want to see…

Eve: [00:06:39] Call me stupid.

Joe: [00:06:42] Well, me too. I live, I bicycle to work.

Eve: [00:06:48] I walk down two steps. I’m in downtown.

Joe: [00:06:50] Ok, that’s even better. So,anyway, it’s and this isn’t to say that we shouldn’t have suburbia. It’s just, allow people to see the real consequences and people will make different choices. I know that if I, I’m Italian, my family has a history of heart disease. I like to eat pizza. I know because of my family history I can’t eat pizza every day. I would love to eat pizza every day. But because of the saturated fat content, I know that eating one slice is my caloric intake for like a week, So,I’ll still eat pizza, but I’ll exercise the whole rest of the week, you know, it’s just keeping things in balance.

Eve: [00:07:26] So,who? Who comes to you for help?

Joe: [00:07:29] Initially, it was activists that were doing conservation and community planning at large. The Sonoran Institute in Rockies. And over in California, the local governments commission. Now it’s we get finance officers, city managers, planning directors, mayors, politicians. Our clients are all over the place. And it’s because our work is more well known.

Eve: [00:07:55] And when did that shift, do you think?

Joe: [00:07:58] Well, initially, here’s what’s funny, I used to work in a real estate development for a company called Public Interest Projects and we were a for-profit real estate development company in downtown Asheville. It’s like basically think of it as a $15 million revolving fund. 75 percent of the money went into sticks and bricks, the buildings, and we reserved 25 percent of that fund to seed businesses and get businesses going on the ground floor. Our time is the direct opposite. We spent more time with the entrepreneurs than the buildings because businesses need help. And then this thing called the recession happened. I don’t know if you remember that, but and what happens in real estate development? We were dead in the water, So,I was actually going to conferences and explaining to people how to articulate the benefits of urban development in downtown stuff and actually started a presentation in Seattle Smart Growth Conference with a quote from Mark Twain that says a person who won’t read has no advantage over one who can’t read. Right? So,that’s a quote about literacy. If you choose not to read, you’re just as illiterate as somebody that can’t read. And I had my hand in the air and I said, OK, who in this room understands the tax assessment system and how property valuation happens in the United States? And I’m standing in front of a bunch of my peers, urban designers, landscape architects, planners. Not a single person raised their hand, and I was dumbfounded. I’m like, look, I’m trained as an architect. I like to look at pictures, but I read the tax system. It’s not hard and it basically is an incentive to crappy buildings. That’s simple. And people came to me like, we just hire you to do that, and that’s how Urban3 got started.

Eve: [00:09:35] That’s really interesting.

Joe: [00:09:36] Probably five years in. It changed.

Eve: [00:09:40] To what?

Joe: [00:09:41] Then it was seen as like, this is some sort of gimmick that this is just, you know, Joe being cute to, OK, we need to do this stuff. When I when I started doing the value per acre analysis…

Eve: [00:09:52] It took five years.

Joe: [00:09:53] People are slow. Good.

Eve: [00:09:55] Good things take a long time. People are slow.

Joe: [00:09:58] Well, it’s all right. It’s good to be skeptical. The irony about all of our work, this is really simple. When you do a per acre analysis, it normalizes all real estate into a metric unit. Like think of miles per gallon. We don’t see miles per tank. So,we all know the gasoline is what drives the car. So, all tanks are different sizes. Well, the same is true with real estate. The irony is like what we’re seen as like just a cute little trick of doing value per acre analysis. And seriously, economists would tell me that they’re like, Oh, that’s a gimmick. I’m like, Are you high? Like, Is there more land on this planet? And so, if you look at literature from the 1930s and 1920s, the development, I’ve got books, historic books from the 1920s about building small neighborhoods. The whole thing revolves around value per acre analysis. That was commonplace back then. Somehow, in the intervening like thirty interesting year gap, we somehow lost this idea.

Eve: [00:10:54] Interesting.

Joe: [00:10:54] Australia, they do it on a per hectare basis. Like they understand the value of land in Australia, but not here.

Eve: [00:11:00] Interesting. Thats’ because most of Australia is desert. Probably. Seriously.

Joe: [00:11:05] You’re alSo,reasonable people. Interestingly, we’re cousins, right? Like, we both came from the same parents. Like we like poke mom in the eye. We were the first ones and then the United States were, like, we don’t need to be British anymore. We left with the same damn tax policies. You in Australia, us in the United States and Canadians. In the intervening two hundred and something years, the Canadians, the Australians and New Zealanders all adapted their tax policies. In the United States we didn’t. Ours is the most crude, blunt instrument.

Eve: [00:11:38] Yes.

Joe: [00:11:38] If you tax on value, there’s a perverse incentive to build crappy buildings, period. That’s it.

Eve: [00:11:44] Right, right. Ok, So,I’m going to break this down a little because maybe I’m one of those stupid people. But I mean, I do understand this, but still. I live in downtown Pittsburgh, and the value of residential is pretty high in downtown Pittsburgh. And I take up a very small portion of land because I live in a unit that is in a building that is four stories tall. Many people live in units that are much taller than that, So,they take up an even smaller portion of land. But the city gets substantial taxes from my unit. If I took my unit and I bought something equivalent in an outlying suburb of Pittsburgh, they had the same value, let’s say, to $500,000 value, OK, $500,000 in a building which has a whole bunch of other things going on it that are alSo,taxed.

Joe: [00:12:37] In taxes.

Eve: [00:12:38] Versus $500,000 on a one-acre piece of land in an outlying suburb. The city gets the same return, right?

Joe: [00:12:49] No, they’re getting well. Let’s just say you’ve got, we’ll go with a coffee shop on the ground floor and three stories of condos, right, for your building?

Eve: [00:12:58] Oh, no, no, that’s what I meant. Yeah, no. They get way more return for the little sliver of land downtown than the one acre on the outlying in the outlying neighborhood.

Joe: [00:13:09] And on top of that, keep going.

Eve: [00:13:09] Yes, let’s see if I get this right. It’s a test. On top of that, you know, the infrastructure is already there downtown. The pipes that bring water into the building and Comcast cable and whatever else you need are there. Whereas if it’s an outlying piece of land that’s never been developed before, someone’s got to pay to get that stuff there, right?

Joe: [00:13:32] And…

Eve: [00:13:34] You can finish.

Joe: [00:13:35] Think of the frontage on that one-acre parcel versus the frontage on your parcel. So, the consumption of cost is 12 times for the frontage versus your frontage, So,in addition to the fact that yours is already amortized its way out and paid for itself, probably in two cycles already, their stuff is like you’ve got to run it out there, you’ve got all the infrastructure that gets you to that point that’s not being paid for because of the existing. There’s a lot of suburbs that you’ve got to go through to get to that end of the line, and all of those suburbs still don’t pay for themselves. So, it’s essentially, we do a lot of work with strong towns. There’s a guy Chuck Marohn, who’s a civil engineer, and Chuck calls it the Ponzi growth scheme, and he’s totally right. The only way that we look, we look solid on paper, the more we grow in suburbia because we’re getting new cash flow. And everybody should have caught this when the recession hit. When the recession hit, all of a sudden, cities were broke. It’s like, well yeah, you should be able to cover your cost if nobody comes in the door and buys a commodity, right? I should still be able to pay rent if nobody hires me. I have a reserve account and we should be able to get through, in our case, our business, we can handle about six months of working without new clients coming in the door. With cities, if they don’t have new permits, all of a sudden, they’re broke. Like that should tell you something. We should tax our system to be able to cover the costs of what we’ve got. In the case of Pittsburgh. When you lost your population, you’re essentially carrying all of this extra infrastructure for a city much larger than you, So,you should not be adding more to it. You’ve got to like, find ways to compact a little bit.

Eve: [00:15:19] Yeah. Now in the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s favor in the city of Pittsburgh, they’ve always really stressed trying to fill out the existing neighborhoods in the support they provide. So, and way back, we had a mayor, Tom Murphy, who, you know, probably familiar with, who really went out on a limb and took operating funds and created a development fund, the Pittsburgh Development Fund, to support projects right in the city because I think he got this, right?

Joe: [00:15:51] Yeah, he did. Like in the case of South Bend, Indiana. Now, the Rust Belt, the big expense of an infrastructure, the big, expensive stuff is lift stations and force means. Everything else gravity feed, you just put a pipe in water goes downhill, but the force means we have to push it uphill or something like that and then lift it. That’s the expensive stuff. So,in 1960, they had 130,000 people, and today they have 103,000 people, So,they lost 22 percent of their population.

Eve: [00:16:22] Which is quite a lot.

Joe: [00:16:22] Yeah, So,but in 1960, they had three lift stations and a third of a mile of force main. Today they have 43 lift stations and 19 miles. So, a 1,000 percent growth in lift stations and a 6,000 percent growth in force mains even though their population was going minus 22. That is a recipe for disaster. When you’re, and cities do this, they’re just like, well, people want new houses out at the edge. So, we’re going to build pipes out there for the builder to build housing. It’s like you were basically building yourself off a cliff. Somebody’s got to pay for this stuff and the developers pay for it. But then they fold it into the mortgage and then the city shows up and like, whoa, new infrastructure. Thanks. Thanks. Thanks, developer. They’ve just taken on this huge liability in maintenance and stuff that doesn’t fix itself.

Eve: [00:17:12] Right. Interesting. So, what’s been the best turnaround story for you? Like, you know, can you describe a client you’ve worked with that perhaps was unbelieving and really kind of transformed their city or at least the processes to?

Joe: [00:17:30] It’s yeah, that’s not an easy question to answer because it’s all been different. And you know, one of the things that you’ll see in our work, and this is something you and I probably have a lot in common in this, that we’re both visual people. I’m a visual learner and a visual thinker. And that’s a lot of people that go into design education get that way. And then we then we get indoctrinated full bore into the design world. So, for me, it’s all about pictures and visuals, and in our work, we make it extremely visual, but some highly nerdy stuff like lift stations and tax flow and stuff like that. But if I can make a picture of it, it communicates to regular people. And what I find with politicians, I mean, think about politicians. I don’t mean this in a demeaning way,

Eve: [00:18:19] But they’re not trained in any civic design.

Joe: [00:18:23] No.

Eve: [00:18:24] Or any of this. They’re politicians, you know, this is a career.

Joe: [00:18:28] You win a popularity contest and you’re like, I’m going to help fix the city and then you show up and you’re like, oh my God, this is a disaster. Where do I start? And then you meet, you meet the technicians that run the city and they’re like planners talking about form-based code or whatever. And you meet the engineer and they’re talking about these, you know, whatever TDM models. You have no idea what they’re talking about, they’re talking in this kind of gibberish. And so, it’s actually a professional problem, not a political problem that the politicians really have no idea what’s going on. So, they just basically just go with the flow, and we take the tack in argument that is the professional that needs to visually communicate, so that people understand it. So, what we’ll do is, we’ll take in South Bend case, Mayor Pete was the mayor when they hired us. We put all the pipes on a map and showed them that they had enough pipe that would go from South Bend, Indiana, to Asheville, North Carolina. And I said, like that, you get to fix that every 40 years. Good luck with that. And once you do that, people are just like, oh my God, we don’t need to add more to this. You know, it should. But like, my mom could understand that.

Eve: [00:19:31] I should not be laughing, but it’s just it’s ludicrous. I’m sorry.

Joe: [00:19:36] Well, it’s systems.

Eve: [00:19:37] Right.

Joe: [00:19:37] You know, it’s you know, you and I talked before the recording. For me, like a very influential author for me is Michael Lewis, and the book Moneyball is brilliant. And so, you know, I worked in real estate development. We’re actually still in the developer’s office. But our company was $15 million. Our city is worth, at that time, $12 billion. Ok, that’s Asheville. 90,000 people taxable value of $12 billion. I know our politicians, some of them are friends of mine. I can’t imagine them running a $12 billion company. And then it’s just like, what do people want? Let’s have more trees. It’s like, I got that. But can we think a little bit more sophisticated than this? And in the beginning of Moneyball, Michael Lewis is talking about the Oakland Athletics being in the playoffs all the time, and they’re the cheapest team in baseball. And and then he meets Billy Beane and they talk about Bill James statistics and the data that Bill James was talking about that was an anathema to baseball. So, the Oakland Athletics were basically following this guy who was asking these really crazy questions like why is an error and error? You know, I fail to close my hand on the ball, but at least I stopped the ball. Shouldn’t we be measuring where the ball lands and where the person is that isn’t catching the ball. So, that distance is really what the problem is because somebody could just never be where the ball lands and they’re never going to commit an error like that makes perfect sense. But in baseball, they’re like, you can’t question the error. We’ve had the error forever. And so, the quote that nailed me in that book, baseball is a is a 7-billion-dollar industry operating without mathematics.

Eve: [00:21:21] Oh, wow.

Joe: [00:21:22] Let that wash over you for a second. I just told you my city is twice the value of all baseball.

Eve: [00:21:28] Wow.

Joe: [00:21:28] And it’s just like Pittsburgh is worth maybe 45 billion.

Eve: [00:21:34] Is anyone using math in Pittsburgh?

Joe: [00:21:39] Some people. I’ve done a couple of presentations there. We actually did a valuation of, took all municipal park property and said, OK, what’s how could you cash flow this? So, there’s the HH Richardson jail that’s at the backside of the county building.

Eve: [00:21:55] That’s a beautiful building. Gorgeous building.

Joe: [00:21:57] Incredible. Modeled after the Bullfinch Jail in Boston, a similar kind of like star shaped plan, although the Richardsons one’s kind of like a half star.

Eve: [00:22:07] Beautiful building.

Joe: [00:22:07] Phenomenal. It’s two-foot-thick walls. But anyway, in Boston, they converted that jail into a lobby for a hotel and stuck a hotel on the back side of it. So,it went from a non-taxable building and it’s actually a really cool lobby. And now it’s kicking out about $3 million a year in taxes. So, went from zero value to $3 million of cash flow to the community. You didn’t lose the building. You know, it’s not a jail anymore, it’s a lobby, but people can go into it. So, we just said, Well let’s just do the same thing with the Richardson jail. The Richardson jail right now, it’s been renovated, but it’s being used for like county offices. It’s like those could be…

Eve: [00:22:49] Family courts, I think. Yeah.

Joe: [00:22:51] Does it need to be in that building?

Eve: [00:22:54] Such a shame.

Joe: [00:22:56] Yeah.

Eve: [00:22:56] So, I just interviewed Jonathan Cohen, who’s the founder of the Society Hotels in Portland, Oregon. And you know, I’ve always thought the riches in jail, like if you had if you had travelers who wanted to stay cheap, you know, what he’s done is he’s created these bunk beds in this old historic maritime building. So, people can stay there for as little as 35 to 50 dollars, pre-pandemic, obviously, and share a bathroom. You know, people who really don’t want to spend $200 on a hotel room. And wouldn’t it be great to stay in a cell like it would be really fun? Maybe not So fun for some people who originally stayed there. But yeah, I’m totally with you. It’s a very weird re-use.

Joe: [00:23:43] And there’s also, there’s a little corner. There’s like a little tiny, little triangular, oddball lot behind it. That’s just this abandoned, weird site where there’s like a memorial out there for something.

Eve: [00:23:57] Interesting.

Joe: [00:23:59] Seriously, you live in Pittsburgh. Go walk behind this, there’s like this…

Eve: [00:24:01] I will. I will.

Joe: [00:24:02] This weird little triangular piece of dirt that’s there. It’s like, really, this thing is abandoned. There’s like a street that is unnecessary. So, what if we just threw the street in in that little triangular lot? And maybe that’s where you put the hotel and you just build a little hotel tower back there and tap it into the jail? Call it a day. The real simple is the quarter acre, which is a huge piece of land in the downtown. We estimated the taxable value of that would be about seventy-five million dollars and that was 2017. So, it’s like, OK, So, you currently have zero on this thing. You can pump that thing up to 75 million. And let’s say you hold it as a ground lease, you say, look, we’re not going to give this to the developer. We’re going to let them lease it for 75 to 100 years. And then we’re going to as the city of Pittsburgh pull that revenue and fund things like Eve. Eve’s doing cool things. We’re going to create a cash flow to fund Eve in equity projects, and she’s going to go off in neighborhoods and help build wealth. We now have a cash flow off this thing. Anyway, we did that citywide. We’re like, we’re not saying get rid of the University of Pittsburgh, but seriously, there’s land all over the city. The current Pittsburgh GDP is $17 billion. We estimated off public assets doing projects like what I just said, or there’s a four-acre police impound lot on the damn river. It’s like seriously.

Eve: [00:25:28] I know I know it. I know it. It’s such a waste of the space.

Joe: [00:25:31] So, yeah, I mean, you could hit it out of the park on a site like that. And it’s like, seriously, this is the best place to put stored cars in Pittsburgh. Anyway, So, your GDP is 17 billion. We estimated you could get about 15.6 billion off existing assets in a way that’s mutually beneficial. Like, that’s a hell of a value game for Pittsburgh. And cities all across the country have that. Yeah, 15 billion is a pretty big deal. I wouldn’t, you know, I would take half that. If you want to give me half that, I’ll be happy

Eve: [00:25:59] And no one would, no one would listen to you.

Joe: [00:26:02] Well, I think they were a little stunned, you know, because it’s just a different way of thinking. And the thing that’s crazy is this is commonplace in Europe. This is commonplace in Boston. This is what you know, Boston. They’re just like, Yeah, we got to use that jail for something.

Eve: [00:26:14] You could basically double the income for the city.

Joe: [00:26:17] It’s double the GDP, the gross domestic product, which is that’s your cash flow of your place. So, yeah.

Eve: [00:26:26] Pretty, pretty significant. And is that what you find in most cities? That you do studies for. Is it a similar? Does it vary greatly depending on the the land available or the history of the city?

Joe: [00:26:40] Yeah. In that and that aspect, yes. Pittsburgh, obviously, you have tremendous riches of these buildings that you can’t reproduce at cost the way that they exist today. So, it’s like you’re in a better position. Places like Phoenix, Arizona, you know, you don’t have buildings like that, but you still have massive tracts of land and surface parking lots and downtown that the city owns. It’s a complete waste of real estate, and they’ll be like, well, Joe, people need parking. It’s like, all right, we’ll build a parking deck and wrap it with a different building that’s producing taxes. You don’t need to. You know, there’s plenty of developers that would kill for that location if you gave it access and you’re actually predictable with the developer. Developer doesn’t want to go through a process of a community design thing where it’s like they have no idea what’s going to happen by the end of it. You know, things cost money, architects, attorneys, all of that. If you drag somebody through a three-year process, they need to make that money back. You know, it’s that simple. And it’s just people just aren’t even thinking that simply about it.

Eve: [00:27:42] Interesting. So, how long have you been in business now with Urban3?

Joe: [00:27:48] 10 years.

Eve: [00:27:50] And how many clients have you had?

Joe: [00:27:53] We’ve worked in four different countries, 40 different states. I don’t, like 150 different cities. We’re slowly becoming like the international tax experts, So, as a by-product of all of this. And there’s really weird things out there like finance departments in government. So, we were sitting down. We were working with Chuck Marohn from Strong Towns in Louisiana. And Chuck and I were interviewing all of the department directors and we sat down with the finance officer. And finance departments keep a depreciation schedule of their roads and pipes and all this stuff. They know what it costs. Yet it’s in a third set of books called the called the Asset Ledger. And Chuck was like, how is a pipe an asset? And they’re like, well, it’s got money, you know, it’s worth money, and so, it’s an asset. And I said, Laurie, can you pick your roads and pipes up? Can you pick them up out of Lafayette, Louisiana, and sell them to Baton Rouge? And she goes, well, no, and I said, that doesn’t sound like an asset to me. I said my computer is an asset to my business, I can sell it, it depreciates. If I had delivery vehicles in my business, those are assets. How is a road an asset? And she’s like, well, that’s just our finance standards and the gap documents that we have to follow. I’m like, who the hell made those? And she’s like, well, I don’t know. So, now you’re the mayor of Pittsburgh and you’re given the books. And your books have costs, expenses and revenues. And then there’s this third set of books called The Assets. You don’t look at the assets, you’re just like, OK, we’ve got a lot of money over, sitting over here. These gifts of gold called roads. It’s like they’re not assets. It’s like this big anchor you’re dragging.

Eve: [00:29:39] A huge liability. Yeah, they’re a liability.

Joe: [00:29:43] So, cities can’t see this because of something as simple as we follow these gap standards. Well, who created the gap standards? The gap standards are created by bond companies. So, bond companies want to know how much stuff cities have so that they know how to turn you into a piggy bank. Because they want to give you more money. It’s like payday loan scandal or something like that. It’s like, oh, here’s another bond. And so, cities are like, we’ve got a AAA rating. It’s like, are you crazy?

Eve: [00:30:13] Are you telling me the bond ratings are based on roads and pipes?

Joe: [00:30:17] Yeah.

Eve: [00:30:18] Oh. That’s a shocker.

Joe: [00:30:21] Mm hmm. No one ever told you that, did they?

Eve: [00:30:25] No. No.

Joe: [00:30:25] That’s the thing is like, you and I go through urban design school, we maybe learn a little bit about a real estate development pro forma. Taxation, maybe like a half day class or half a class on that and one session about municipal finance.

Eve: [00:30:39] I don’t think I had any when I went through school.

Joe: [00:30:42] Yeah.

Eve: [00:30:42] And what’s more, I don’t think architects get any.

Joe: [00:30:45] Oh God.

Eve: [00:30:46] I mean, architects are woefully undereducated when it comes to both real estate development and finance.

Joe: [00:30:53] I would say wilfully ignorant. I wouldn’t say woefully undereducated because we, and I’m saying putting myself into that bucket, it’s like, Oh, that’s finance. I am a designer. I am above that. It’s like, Oh, really, OK?

Eve: [00:31:08] As a developer, we sit at the table with an architect thinking, please don’t draw that line. It’s going to cost me too much money.

Joe: [00:31:14] Yeah. And it’s and it’s sad because I love architecture and I love the profession. I think the best education you could have is an architectural education because you’re basically given a blank piece of paper and they’re like, OK, now be creative.

Eve: [00:31:27] Oh, I so completely agree with you. I think architects are trained to be problem solvers, to turn nothing into something. It’s an amazing education.

Joe: [00:31:36] And be critical thinkers. And so, it’s like, All right, take that same critical thinking skill and just be a little curious over about finance. And in defense of architects, the language that people use in finance is deliberately opaque. And I think that’s the best thing about that movie, The Big Short, where they make fun of the opacity of financial language. Well, the same is true inside real estate development. We’re going to get some mezzanine financing. I used to sit in meetings with people. I’m like, What’s the mezzanine? And I would just do that just to be an idiot. But I was mostly making fun of the fact that this has created fictitious language, and I’m explain it to me, I’m just a dummy. I only went to Harvard. What do I know?

Eve: [00:32:16] You know? Yes. And what’s a sponsor? There is a lot of secret language in the real estate world.

Joe: [00:32:24] Yeah.

Eve: [00:32:24] And I have to say this about the SEC in the regulation crowdfunding rule, they created one of the regulations, one of the things that you have to do is explain things in plain English. So everyone can understand. And I kind of love that because what is the sponsor? What’s a capital stack? What’s the mezzanine? What’s like, you know, all of this stuff is like for very special people, but everyone should have access. Yeah.

Joe: [00:32:49] And it’s funny when people, you watch people and you’ve been hanging out with people like this, there’s like, oh, I got my capital stack and it’s like, I just picture people with like a big pile of money that they’re walking around with and they’re like, look at me with my pile of money. Like, you’re just like, come off as the biggest fool when people talk that way. But it’s like, I don’t know, I’m suspicious of that because it’s like, what do you really, did you really work at this or do you just know somebody that’s a banker? They gave you access to money, and you’re proud that you succeeded because you have access and availability that John and Jane Doe off the street don’t have that access. Or somebody that, God forbid, is a different color skin doesn’t have access to the same power and wealth that you’ve got. So, let’s talk about that and there’s matters of inequity baked into the system through the whole thing.

Eve: [00:33:36] Yes, I think the real estate industry is probably one of the most inequitable industries.

Joe: [00:33:42] We’ve done analysis of redlining in Kansas City, and we showed them that even today, when you drop the Red Line map onto the model, you see this staircase step down from green to red, So, you know the gradients of redlining.

Eve: [00:33:59] No, I don’t know the gradients.

Joe: [00:34:01] Oh, OK. So, in 1934, the Federal Housing Administration changed mortgages from seven years in the United States to 30 years. Think of that. That’s a huge change to the mortgage industry. And they said, you know, basically the dirty little secret here is these are Democrats doing this and they were doing it because we were afraid of socialism. So, our country was looking at Europe in the depression going, OK, this is a little freaky. They’re becoming socialists. We need to do something to make people homeowners so that when they own something, they’ll be less apt to want to be socialist. So, let’s find a way to make more homeowners in the country. And this is in the middle of the depression. And so, they created this system of we don’t know what Pittsburgh is like. We don’t understand Pittsburgh, but you have to come up with a map in Pittsburgh to map what’s good real estate, what’s desirable real estate, what’s declining real estate and what is hazardous. So, those are the four grades, the hazardous areas were the red areas. And so, arbitrarily you mapped your hazardous real estate, by like if it was next to a train yard or if it had an infiltration of immigrants. Or if it had Negroes.

Eve: [00:35:16] So, who did that mapping?

Joe: [00:35:19] Our local people. So, it was Pittsburgh did it to themselves. Asheville did it to themselves, cities 50,000 and higher did it to themselves. They did it in Kansas City. Incidentally, my favorite one is in Denver, where they took an Italian neighborhood, because coincidentally Italians were the driving immigrant class of the 1930s and coming in at number two, where Germans. Well, what kind of Germans were coming in in the nineteen 1930s? That would be Jewish people. So, you find Italian neighborhoods and Jewish neighborhoods were redlined as much as is black neighborhoods.

Eve: [00:35:56] That’s interesting.

Joe: [00:35:56] Now what’s interesting about Italians is I can change my name to Smith, you know, or there were Italian neighborhoods in Denver. There was this one neighborhood that wasn’t redlined that was Italian, 50 percent Italians. And they wrote, right in the document, these Italians peddled liquor during the prohibition era. It’s like those are the mafia Italians. We’re not going to redline them. So, but as a black person, you can’t change your skin.

Eve: [00:36:20] No.

Joe: [00:36:22] So, your family wakes up that day that the map is adopted, and they can’t sell the house, right? Because no one can get a mortgage in that neighborhood. That went on for 30 years from 1934 to 1968. And so, for three generations, you don’t get, you can’t get a home rehab loan. You’re basically just disconnected from the financial system of our country.

Eve: [00:36:45] I realized that I just didn’t know how the initial mapping happened, I suppose.

Joe: [00:36:52] Well, we ran the number in one neighborhood in Kansas City, Kansas. Is like a half square mile where there’s just all vacant houses in it. Well, not all, but 700 vacant lots. And we just real simply went back in time, pulled the old values from 1930, glued the houses back on the map and ran a cash flow of if those houses just stayed low value but paid their taxes over time, how much taxes would they matriculate over 30 years? And it’s insane. It’s $30 million. So, when I was presenting to the community, I said, Look you need to realize your great grandparents were racist, period. There’s no way around it. They adopted racist policies. This neighborhood was redlined because it was black, and you basically wrote a check for 30 million dollars and flushed it down the toilet. That’s the cost and consequences of being racist. Now that was just one neighborhood. What did you what did you blow in the entire city?

Eve: [00:37:43] Wow.

Joe: [00:37:43] And that’s the thing that we need to. I think I would argue that that’s part of being anti-racist, is you have to point out the racism that happened and make it a way that people can understand it. It wasn’t at all comfortable to say that on stage in Kansas City, but that’s the truth.

Eve: [00:38:00] Interesting. So, I have to ask you, also, what does your team look like? How do you hire people in your office? Do you hire architects?

Joe: [00:38:12] God, it’s funny. We have one urban designer other than me, several planners. Most folks are GIS based. It actually, really, we don’t fully get into design the way that an architect or designer would. We’re information curious and a technically proficient with GIS software. The design side we can train internally, but we’re mostly looking for creative thinkers that understand this technology but are also ridiculously curious about systems in cities and have a sense of humor. We do a lot of joking in our presentations, in our data, is a method of delivering information because it’s pretty depressing to just drop a bunch of redlining stuff on people.

Eve: [00:39:05] Anyway, someone who has a sense of humor has probably a higher IQ, right?

Joe: [00:39:12] Well, it’s also, I don’t know, if you’ve read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Eve: [00:39:16] No.

Joe: [00:39:19] The guy is a psychologist at one. He won a Nobel Prize on behavioral economics or in economics. He and Amos are the godfathers of behavioral economics. And there’s a third one. His name is Richard Thaler, who also won a Nobel Prize in economics. And the three of them did all of these studies about how do people make the wrong decisions economically? And it’s there’s human flaws in the way that our brains operate. But there’s also ways that you could take advantage of those. One is where we’re as a species, we’re oral communicators. We tell stories. So, people need a narrative of understanding the economic data. We just don’t drop like a spreadsheet on somebody. We actually tell stories with the data. The other thing is like simple things like they would put pencils in people’s mouths. And you can see my camera and nobody else can, but. And they put one cohort of students through these tests with pencils in their mouths. In another cohort of students through the same test without pencils. And the students with the pencils in their mouths learn more than the students without. And what they figured out is that So, you watch my face? I’m smiling. You know, if you put a pencil in your mouth, you’re forced to smile, and when you smile, the back of your neck opens up. Your brain operates differently than if I’m sitting in the class with my arms folded and I’m like, looking at you like this, you know, it’s just there’s ways of learning that we have survived with and that we just basically use that. So, I highly recommend actually one of my favorite books is Misbehaving by Richard Thaler. And he’s one of the three Nobel Prize winners. Daniel Kahneman is awesome. His book, Thinking, Fast and Slow is incredible. I find it really hard to read. I much prefer Daniel Ariely’s, Predictably Irrational.

Eve: [00:41:12] These are all great titles, you know?

Joe: [00:41:15] Yeah. Well it’s, look, we deal with humans, you know. And we don’t, we go to design school. Even planners. Planners of all people should have degrees like some subset of psychology, you know, because they have to deal with groups of people. But it’s funny that we go into these professions, and we don’t learn how humans operate.

Eve: [00:41:34] So, I’m fascinated and I’ve lost my train of thought here completely.

Joe: [00:41:39] I’ve taken you off course. We’re supposed to be talking about real estate, aren’t we?

Eve: [00:41:42] No, but this is good. So, if cities adopted, you know, sort of this data exploration, what would cities, what would cities look like in the best of best of all worlds if they really paid attention and adopted, you know, this information that you’ve uncovered to their advantage? And what would we have to stop doing now that we’re doing?

Joe: [00:42:15] Well, it is. That’s a hard question. You know, there’s ultimately, I think we need to change our tax system. And right now, the majority of cities in the United States counties to operate off property tax. And So, think of it this way your building is probably worth what a square foot? Like maybe like 500 bucks a square foot?

Eve: [00:42:42] Oh, I’d be so lucky. Maybe 300.

Joe: [00:42:46] Ok, even 300. Like, what would it, you’d pay $300 a square foot to reproduce your building?

Eve: [00:42:52] No, but I couldn’t probably sell it for more than that.

Joe: [00:42:57] Ok, let’s call it 300. What’s a Walmart worth per square foot?

Eve: [00:43:01] Boy, I don’t know.

Joe: [00:43:02] Fifty. So, per square foot, you’re paying six times the production of a Walmart.

Eve: [00:43:11] Yes.

Joe: [00:43:13] That’s simple math, right?

Eve: [00:43:14] Right.

Joe: [00:43:15] That’s our tax system.

Eve: [00:43:17] Interesting.

Joe: [00:43:19] And it’s just like, what, so architects, of all people, we should be at the front line saying get rid of property tax as a valuation of property value is the indicator of taxation because there’s a perverse incentive to build crap. Wal-mart doesn’t make any bones about it. I actually went to, I presented at the International Association of Tax Assessing Officers Conference. I don’t know if you hang out…

Eve: [00:43:41] That must have been a blast.

Joe: [00:43:43] Oh, it makes it makes an AIA convention feel like Burning Man. It was the squarest thing ever. And but, you know, they’re cool people. I like, I love assessors. And the thing is like, there’s no other designers there. And I’m like wandering around with all of these nerds. I’m like, How the hell does this system work? Trying to learn from them? And the more I learn from them, I’m like, wow, that’s amazing, the way that they think. They like, go into a forest and they’re just like, is, is this a Norwegian spruce or is this a Douglas fir? I don’t quite understand what tree this is. It’s like, do you see the forest that’s around you? And they don’t. And so, they have their biases just like any other profession, and they are completely obsessed with figuring out what kind of tree this one tree is. And they will have an entire week’s long conference about that and not see the forest. And the head of Walmart’s real estate got up there and was the keynote speaker one morning. And I remember this, 3,000 assessors in the room. This guy did this amazing presentation on how cheap Walmarts are. He showed spreadsheet after spreadsheet on how crappy is buildings are. And I’m like in the audience drinking my coffee and I’m like, oh my god, this is brilliant. This guy is the bomb. This is the smartest thing I’ve ever seen anybody do. You’ve got 3,000 assessors in one meeting. You can get all of your property taxes lowered in one meeting, right? And then I’m like having a coronary because as a designer, I’m like, Holy cow, how is he getting away with this? Now, assessors in their defense, they’re agnostic. If it’s crap, it’s crap.

Eve: [00:45:15] It’s not about design. It’s not about, yeah.

Joe: [00:45:18] They’re like, thanks for making our jobs easier. So, I go up to the microphone and I was trembling. I was so, pissed off and I was like, Mr. Tyrrell, what’s the useful life of one of your buildings? And he goes, 15, maybe 20 years. We designed the building to depreciate it as fast as possible. We don’t care about the buildings. They’re throwaway. We’ll design another building, build another building, move into it and start the depreciation cycle down again. We don’t care about the buildings; we care about the transportation system. And once we set up a transportation system of goods and services, the buildings are thrown away for us. And I was like, damn. Like, that’s the life cycle of a cat. 15 years, you know, and so, when I present to people, I actually make fun of that experience and I actually show a big picture of a cat and I tell the mayor I’m like, is that what you want in your corporation? Is the CEO of a corporation that’s worth whatever, $15-billion, do you want a cat? And as long as you’re making that choice, that this is what you need. Awesome. The average Walmart consumes more in police services than it pays in property taxes. So, I tell people…

Eve: [00:46:17] Wow.

Joe: [00:46:18] Don’t hate the player. This isn’t about Walmart. Hate the game. Understand the game is in your control. And until you control it, you’re at the mercy of the game. So, cities that don’t look at their cash flow situation, they have these biases that roads and pipes are assets and not even look at them as liabilities. That’s their own stupid fault.

Eve: [00:46:37] Right.

Joe: [00:46:38] I’d like I wish we could all live in a version of Paris or something or Milan or, you know, I think you go to Europe, and you see these incredible cities and you’re like, what kind of what kind of Martians left these places for these people to live and happily? And then you come to American cities, and we live in such rubbish.

Eve: [00:46:58] Well, it’s partly the culture of the country. Like, you know, I lived in Australia, and I’ve lived in the states. And so, there’s a real cultural divide when it comes to ownership rights. You know, and property rights, and you should have complete control here over whether you can park your car in your front yard. Whether you can cut a tree down because it’s going to make your car dirty. It’s really not about the neighborhood as a whole or even the environment as a whole. You get to cut your tree down. It doesn’t matter if it looks bad like, or it doesn’t matter if it devalues the neighborhood. You can’t do that in Australia. In Australia, if you want to cut a limb off your tree, you have to go to City Council and get approval. Like it is, and people accept that. You know, they kind of accept that as the status quo. So, I think, you know, I don’t know what it’s like in New Zealand or in Canada, but that’s definitely, I think the dividing point I see. Does that make sense?

Joe: [00:48:04] You know, back to the point I made earlier that the interesting thing is culturally, we’re really not that far from you. We’re both basically British descent as countries go. Both about the same size. You had as much land as we did or more. Australia is a big country, but most of it’s desert. In our country, we kind of how do I put this? We have these narratives, and this is where the psychology comes in. So, we talk about freedom and all this stuff. But think about our country. Our country was formed on a tax revolt, right? We were taxed differently about our tea. We weren’t in control of it. So, we got pissed off at mom and dad and started a little fight and separated our country from their country. So, there’s a great old colonial barb in our country that people used to say as colonists, Don’t tax me, don’t tax thee, tax the fellow behind the tree. I love that saying. We’re a country of tax evaders. That’s it. And it’s like, and we’re fiercely independent, which is cool. And you know, there’s I live in Appalachia. You’re part of Appalachia. I was like in a meeting one time I got into this argument with this guy and you know, we went to breakfast the next day and he gave me his political philosophy and he’s like, Look, Joe, I run out in the woods with my gun. I go out with my gun and get out in the woods, and I run around, and he was doing this kind of like sitting in his chair, like he’s Chubby Checker doing the twist or something. He’s like, I run with my gun and I’m so happy. And like, you know, Steve, I don’t care. Do whatever you want with your gun. I don’t care if you sit in your yard and get naked and rub yourself on the belly with a chipmunk if that makes you happy. Knock yourself out. Would I have a problem with is that road to your house? You get to drive on that road every single day and you’re not paying for it? I think there needs to be a toll gate at the end of your driveway and you pay to use that road. And then when I go to drive past your house to go out mountain biking, I’ll pay to use that road too. And everybody should pay their own fair share. And he just looked at me and he goes. You know, that makes a hell of a lot of sense.

Eve: [00:50:16] Interesting.

Joe: [00:50:17] You know, So, rather than, what I find with people is we’re really good at this in our country. More so, now, is we will take our own little tribe and stay in our bucket and blame the other tribe without going across to understand their mindset. So, I understand Steve’s mindset. I understand the freedom because he’s been led down the primrose path that that’s some sort of American mythology until he’s confronted with the cost of that road. He doesn’t know that the road cost money. You know, he doesn’t pay for it. So, what I’d like to do is I’d like to see Steve get a tax bill that shows him his subsidy So, he doesn’t run around thinking he’s thinks he’s paying for himself. So, when we show that model, the reason why we do it county wide is in, particularly in my county, I’ve got two voters out in the county for every one voter in the city. Those folks out there control the place politically. They’re subsidized, So, they hate my city. In fact, they got my state legislator to call us a cesspool of sin.

Eve: [00:51:17] Oh.

Joe: [00:51:17] And that was on the downtown. Seriously and we’re out on the downtown association. And we’re just like, really? How about a thank you card for all the money we’re shelling out? We showed the model showing how much more taxes is coming out of downtown. Remember everybody in the county pays the same millage rate. So, we’re paying. I pay six mills in county taxes. People out there pay six mills. Their value, you can see it in the model is like one 20th what my value is. So, on a per square foot basis, I’m kicking out 20 times the taxes that they are. When you show it to them on the map, you’re just like, OK, so, what you’re saying about that subsidy that you guys have? You know, then they can see it. So, it’s really, it’s all of our responsibilities to try to find a way to communicate. And make a common ground, and that’s kind of why that’s our practice.

Eve: [00:52:06] Well, it sounds like you’re doing an amazing job and I have thoroughly enjoyed this conversation. I could go on forever. I’m such a nerd. I love this stuff. You showed me a pretty fabulous PowerPoint, which I would love to at least point to on our blog post for our listeners. Maybe you can give me a link, or I can post it there.

Joe: [00:52:28] Yeah. We’ll send you a link. We have a YouTube channel with a bunch of videos.

Eve: [00:52:32] Oh, that’s perfect.

Joe: [00:52:33] Some of them are super long. So, just for the audience, just be aware. But, but really, it’s their narratives. They’re all three act plays as far as I’m concerned, So, we do work real hard to make them fun to watch because it’s highly nerdy stuff, but you’ll see the visuals and the presentations.

Eve: [00:52:52] Well, thank you so much. I’ve really enjoyed the conversation and I hope we can continue it.

Joe: [00:52:57] Definitely. Thanks for having me. And anytime you want me back, just let me know.

Eve: [00:53:16] Joe brings energy, passion and a brand-new perspective to the built environment. If you look at the data, good stuff will follow. You can find out more about this episode or others you might have missed on the show notes page at our website, Rethinkrealestateforgood.co. There’s lots to listen to there. A special thanks to David Allardice for his excellent editing of this podcast and original music, and thanks to you for spending your time with me today. We’ll talk again soon, but for now, this is Eve Picker signing off to go make some change.

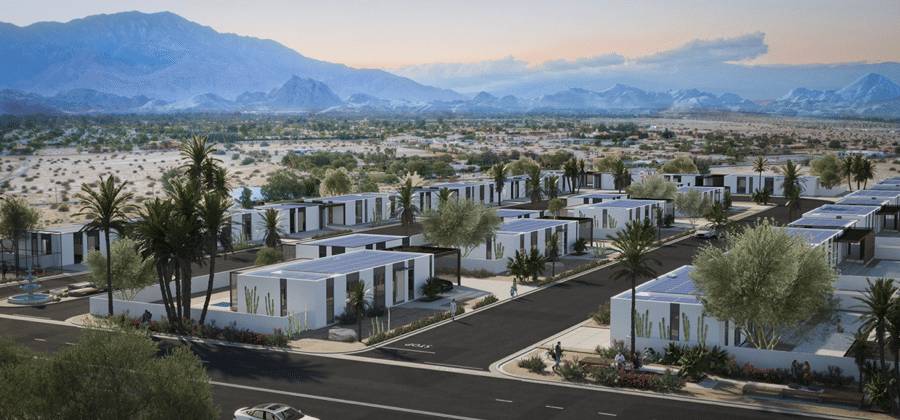

Image courtesy of Joseph Minicozzi, Urban3