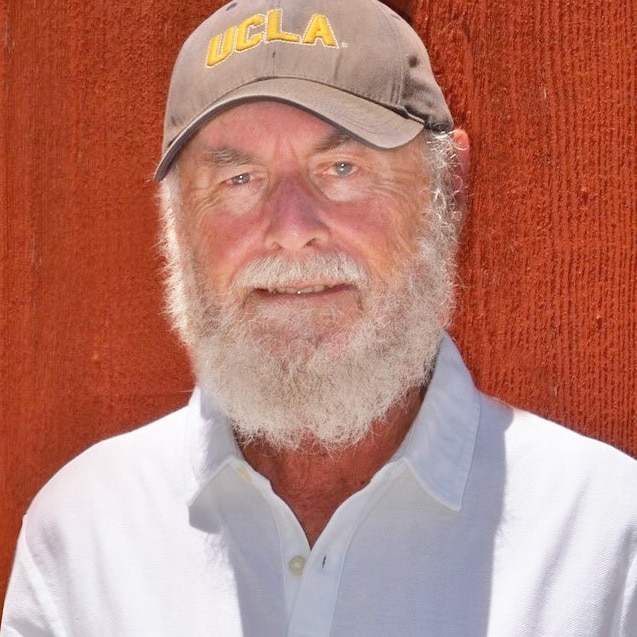

Donald Shoup’s large body of work centers on the connected urban issues of parking, transportation, public finance and land economics. A Distinguished Research Professor at UCLA, he is perhaps best known for two books: The High Cost of Free Parking (2005), which turned an otherwise academic topic into a significant policy issue; and as the editor of Parking and the City (2018), which makes the case that parking reforms can improve urban metro areas both economically and environmentally. This book has become widely cited as cities debate how to reduce parking to make room for other new modes of transportation, or other land uses.

Donald initially became interested in the impact of parking years ago when he came across data suggesting that free parking in Los Angeles led to commuters often driving twice as much. He became known for popularizing the idea that an 85 percent occupancy rate of on-street parking is the most efficient use of public parking, and for advocating for the idea of “parking cash out,” where employees are offered either a parking space at work or a cash payment to give it up. He has also written about how to promote higher density infill projects through new zoning ideas, such as ‘graduated density zoning.’

Donald is a Fellow of the American Institute of Certified Planners and an Honorary Professor at the Beijing Transportation Research Center. He has received the American Planning Association’s National Excellence Award for a Planning Pioneer and the American Collegiate Schools of Planning’s Distinguished Educator Award.

Insights and Inspirations

- There are 3 million on street parking spaces in New York and 95% of them are free.

- Donald advocates for demand parking rates. If there are always a couple of empty parking spaces available, the right price is being charged.

- Parking spaces are cash registers at the curb, says Donald. Municipalities should charge for parking everywhere and use those funds to beautify the streets they were collected from.

Information and Links

- In his 2005 book, The High Cost of Free Parking, Donald recommended that cities should charge fair market prices for on-street parking, spend the revenue to benefit the metered areas, and remove off-street parking requirements.

- In his 2018 edited book, Parking and the City, Donald and 45 other academic and practicing planners examined the results in cities that have adopted these three policies.

- Parking is sexy now, thanks to Donald Shoup.

Read the podcast transcript here

Eve Picker: [00:00:00] Hi there, thanks so much for joining me today for the latest episode of Impact Real Estate Investing.

Eve: [00:00:06] My guest today is Donald Shoup. Dr. Shoup is a distinguished research professor with a focus on economics in the Department of Urban Planning at UCLA. He began studying parking as a key link between transportation and land use with important consequences for cities, the economy and the environment. His book, The High Cost of Free Parking, turned an otherwise academic topic into a significant policy issue. A second book, Parking in the City showed that parking reforms can improve urban metro areas, both economically and environmentally.

Eve: [00:00:47] Be sure to go to rethinkrealestateforgood.co to find out more about Donald Shoup on the show notes page for this episode. And be sure to sign up for my newsletter so you can access information about impact real estate investing and get the latest news about the exciting projects on my crowdfunding platform, Small change.

Eve: [00:01:08] Hello, Donald. I’m really delighted that you’ve been able to join me today.

Donald Shoup: [00:01:13] Well, thanks for inviting me to Dallas.

Eve: [00:01:15] Yes. You’ve spent your career deeply immersed in parking and land economic issues, both of which are really hot button subjects right now. So, I’m wondering, first of all, how did you get interested in the economics of parking and why?

Donald: [00:01:33] Well, like everybody in parking, I think I backed in. Nobody wants to grow up to be in the parking business. They say, well, I was doing my PEC Dissertation in economics. I was working on land economics. So, I came to it from that angle looking at development and the value of land. And later on, I noticed that the market is the single biggest user of land of American citizens, the curb parking and the off-street parking. But it had almost no interest from any academic or even a lot of other professionals of the parking industry. But they were looking at it from the view of land economics. So, I had the field to myself for a long time.

Donald: [00:02:29] Universities always strongly advocate equality and equity, but they are very rigidly hierarchical in their own operations. Everybody has different titles like Chancellor or the Vice Chancellor or the Deans and the Professors, and the Associate and Assistant Professors and lecturers and even the students, you know, the seniors and juniors and sophomores and freshmen. So, I think it’s not just that we’re hierarchal, but the things we study are also hierarchical, like international affairs are very important and national affairs are too. But state affairs are very, a big step down and local affairs are parochial. And then I think the lowest status topic, you know, even in local government would be parking. So, I was a bottom feeder for about 30 years, but there was a lot of food at the bar. And that’s, that’s how I got into parking. It was so easy to discover new things that nobody, well not many people, have been paying attention. But now there’s almost a feeding frenzy. A lot of people are getting to study, at least among academics, or just studying parking and its effects. I think that’s what you’re interested in, not parking itself but how it affects the real estate of the city and the economy.

Eve: [00:03:58] Yes, and housing, right? So, you said it takes up a lot of land in American cities. How much land does parking take up on average?

Donald: [00:04:08] Well, nobody knows. It’s highly regulated but the, no city, except San Francisco, has any census of parking that… You couldn’t go to your city council or city planning department and say, how much parking is there in Dallas? They don’t know. Although they regulate it very heavily on every site, there’s no aggregate number that applies to all cities. But people who have looked at it in various ways think that, oh, maybe about 30 percent of the land is used for parking.

Eve: [00:04:48] Which is a lot of land. One of the statistics I read was that New York City, which has really high housing costs, actually is the eighth most affordable city out of 20 because the land is used really economically and there’s less parking. The two certainly go hand in hand, don’t they?

Donald: [00:05:10] Well, New York is a very special case, but most cities are like it. Several, the Department of Urban Planning’s estimated there are about three billion on-the-street parking spaces in New York and nobody knows how many off-street parking spaces. But of those three million…

Eve: [00:05:29] That’s a lot.

Donald: [00:05:29] …on-street spaces, only three percent have parking meters. So, 97 percent of all the car parking in Manhattan, in all of New York City, is free to the driver. So, of course, a terrific competition for it and it’s a nightmare trying to find a parking space in Manhattan because it’s free and lots of other people want it. So, there’s an incredible amount of cruising around, hunting for parking. Seinfeld often talked about it. I think one time in an episode, George is coming to Jerry’s apartment and Elaine is in the drivers, is in the passenger seat, and they can’t find a parking space. And she said, well, let’s park underground at the building. And he said, no, I never pay for parking. Paying for parking is like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay if, when I apply myself, maybe I can get it for free?

Donald: [00:06:31] So, I think that we’ve all been trying to get it for free for as long as we’ve had cars. And everybody wants to park free through to you and me, but we have twisted our cities is totally out of shape and real estate development totally out of shape with parking requirements that ensure that every new development has to have plenty of parking. So that won’t overcrowd the free curb parking. So, I think that I’ve seen studies. I think, yes, the Department of Commerce did one study saying that: What is the biggest impediment to real estate development? Is it property taxes? Is it leverage issues? And almost everybody says it was required parking.

Eve: [00:07:17] Yeah. And have you seen a shift at all, over time in the last decade or two, the attitude towards parking?

Donald: [00:07:25] Oh, I think so. I’ve recommended three basic things. One is to charge the right price for curb parking, which is the lowest price that cities can charge and still have one or two open spaces vacant. So, nobody can say there’s a shortage of parking because everywhere they go, they’ll see one or two open spaces. But like real estate that’s valuable, it won’t be free. And then to make this politically popular, because drivers don’t want to pay, is that the cities dedicate the meter revenue to pay added public services on the metered streets. You know, fix the sidewalks, plant street trees, clean the sidewalks, extra, well I shouldn’t say police patrol right now, but, extra security. And some say to give free Wi-Fi to everybody on the block that has market-priced curb parking. So that people can see the benefits of charging for parking. Instead of having the money disappear into the general fund. So that’s one policy to charge the right price and the second is to spend the revenue on added public services. And then the third one is to remove off-street parking requirements.

Donald: [00:08:39] And you’ve seen, all three of these happening in various cities. Houston just recently increased the share of the city that has no parking requirements. Houston is famous for having no zoning, but it has very elaborate parking requirements, just like any other city. Except for downtown, that they recently increased the area of Houston that doesn’t have any parking requirements. And some cities have removed parking requirements entirely. San Francisco removed all its parking, off-street parking requirements, and Buffalo did, Hartford and London and Mexico City. It’s spreading. I think that I and other peoples have preached the gospel that parking requirements do a lot of damage, that they raise the price of housing, they increase traffic congestion, they increase air pollution, they even contribute to global warming.

Donald: [00:09:43] So, I’ve never heard anybody, planners say: no, minimum parking requirements do not have these effects. The opponents of parking requirements are proving with study after study saying how it reduces the available land for development because so much of the space has to go for required parking. And it does increase housing prices at, and the prices of everything, because the cost of parking is hidden in the prices of everything else. Parking requirements make parking better, but they make everything else worse. And, as I said, I’ve never heard any urban planner say: no, parking requirements do not have these bad effects. I don’t think you could find any professional in the planning industry or development industry who would say: no, parking requirements do not have these effects.

Donald: [00:10:39] So, I think some cities have begun to remove their off-street parking requirements. Others have begun charging, you know, what I call the right price or demand-based price, based on the demand for this scarce land. And they’re spending it all on the, spending the revenue in the immediate district. So, I think all these three things are happening. So, I think the future of parking’s here is just not evenly spread.

Eve: [00:11:08] Right. So, you know, Covid19, the pandemic, has probably accelerated a bit of this thinking. I’ve been watching news about cities like Milan in Italy, grabbing street back for pedestrians before they’re fully occupied by cars again. And I’m wondering if you believe any of that will sort of help accelerate a move towards less parking, more purposeful use of valuable land.

Donald: [00:11:40] I’m sure it will. Covid19 has opened our eyes to a lot of things and one of them is a transportation. People are saying cities with very few cars, but a lot of pedestrians, and a lot of cyclists, and people eating at outdoor restaurants on the curb lanes, they could see that this is a lot better looking than having all the curbs completely jammed with cars and other cars hunting for, to find spaces being vacated. So, I think that it will lead to big reforms and it already is. Many cities have suspended the requirements of parking that the required parking lots have to be used for parking. They say, oh, you could use them for restaurants, outdoor restaurants with widely separated tables.

Donald: [00:12:34] But now in Dallas and every other city, they would say, if you want to have more outdoor city, you have to have extra parking for it. Most cities don’t allow parking to be converted into outdoor restaurants. Everybody wants to eat outdoors. But you can’t allow the required parking spaces to be used for a restaurant because that’s against the parking requirements. So, I think that cities are experimenting. I have no idea if Dallas has done it, but a lot of cities have allowed restaurants to expand into their parking lots for outdoor dining. It will show people that there are better uses for land than storing empty cars. And, even if they’re used for storing empty cars, they’re still vacant most of the time.

Eve: [00:13:21] They are, they’re vacant.

Donald: [00:13:22] If there’s all those building where the parking spaces are empty during the evening, schools — the average car as parked ninety five percent of the time so there have to be an awful lot of parking spaces wherever you go, because how can you drive somewhere, where there isn’t plenty of parking? But if we think, we thought of parking as free parking and, even in downtowns like in Dallas, a lot of the people who drive to work get free parking. Is it paid for by the employer? You get free parking where you work?

Eve: [00:13:57] I don’t park. I live downtown and my office is two floors below where I live. So my commute is very short, and I rarely, rarely drive.

Donald: [00:14:08] But in your apartment, are there a parking space or two available to you?

Eve: [00:14:13] Well, I have a tiny little building that has two spaces for the entire building. It’s a building I built so it’s a bit unusual, it’s probably not a fair comparison.

Donald: [00:14:23] How did you build it without a lot of parking?

Eve: [00:14:26] Because it’s downtown and in downtown Pittsburgh there’s no parking requirement for residential.

Donald: [00:14:32] Oh, you’re in Pittsburgh?

Eve: [00:14:33] Yes, I am in Pittsburgh.

Donald: [00:14:35] Oh, I thought you were in Dallas.

Eve: [00:14:37] No, I’m in Pittsburgh. So, downtown Pittsburgh for quite a while has had a zero parking requirement for downtown residential.

Donald: [00:14:45] Yes, yes.

Eve: [00:14:46] Not that the market didn’t demand parking, right? That was when the market, the downtown market started here for residential. It was very hard to get going because people wanted to park their cars downtown. But I think in the last 10 years, that’s really shifted. But I can’t say that’s extended to other neighborhoods. Somehow people feel entitled to have a car and a parking space.

Donald: [00:15:11] Pittsburgh does a lot of things right. The director of your parking authority is very famous in the industry, David Onorato, and I think they have some very good ideas. Say around Carnegie Mellon University, the university is the one who pioneered the policy of charging demand-based prices for curb parking. You know, they monitor the occupancy rate and they recommend the price that should be charged. So the best spaces have higher prices, than the distant spaces. I don’t know if it was in Pittsburgh, whether it was just an idea or whether it happened, but, in some city, say, a grocery store will have a meters by the, spaces near the front door.

Eve: [00:16:00] Oh, interesting. That’s interesting.

Donald: [00:16:01] You pay for, at a meter. The rest of the lot is free, and the meter money goes to pay, to charity. So, when you put your money into the meter you know that it isn’t going to programs, but it’s going to a local charity and they say what it’s going to. So, I think that’s another way to slowly bring prices into managing and parking.

Eve: [00:16:26] Yeah, that’s really interesting. You know, you see a lot of strip malls where, you know, you have a sea of parking out the front or even in small main streets where there are parking requirements that really, kind of, force architecture that’s overwhelmed by vehicles. And I worked at the planning department for a while, and I know what it takes to change a code, you know, a zoning code with the requirements, it’s a mammoth and expensive exercise. And so, we have many smaller boroughs all over the country that have pretty old zoning codes now that require parking, and I really wonder how they’re going to shift into, sort of, this new thinking.

Donald: [00:17:14] Well, it is very difficult to reform zoning for parking piecemeal that often on individual developments the developer will ask for a variance and say that “I don’t need so much parking as you should require” and they to get a consultant show that this is true. There’s so much study goes in to say, “If we if we reduce the parking requirement, well what should the new parking requirement be?” because it’s all pulled out of thin air, there’s no science at all. I mean students learn nothing about parking in their graduate studies because the professors have nothing to teach them. But they do learn that whenever they have a development project of their studios, the thing they have to worry about most is the parking requirement.

Donald: [00:18:02] So I recommend that cities should just remove off-street parking requirements. As I say, in Buffalo they had pages, like Pittsburgh does, pages of parking requirements, and it was replaced by one sentence and the zone goes: there’s no work parking required for any use. That was so much easier than saying, well, let’s have a study and say should they be cut by 20 percent or 30 percent or maybe the parking for a nail salon is too high, or something like that? That it’s better to, to just say there are no parking requirements except for handicap spaces and specially what they should look like – the landscaping of them, and the water run-off and the location. The quality of the parking is what planners should regulate, not the quality. But in the U.S. we have a huge quantity of very low quality urban designed parking.

Eve: [00:19:05] Why do you think there’s so much resistance to that? I think it’s a brilliant idea because a real estate developer who has financial risk in building a building is going to think very hard about how much parking they need to market their building.

Donald: [00:19:19] Of course, and they know how much a parking space costs. The ramp parking space will easily cost fifty thousand dollars. And whether we talk about the need for parking, they’re not talking about how much, whether people are willing to pay that much. I don’t want to get into today’s particular issue about Black Lives Matter. One of the things that I did through the years, I pointed out the fact that parking requirements strongly discriminated against low income people. Now we have measures of the net wealth of the population, you know, all your assets, minus all your liabilities. And of course, many young people have a negative net worth because they have student debts and no assets. Maybe a car or a cell phone. But I have looked at the median net wealth of Black families is about seventeen thousand dollars. Where for white families another hundred and sixty thousand, I think now. But cities are requiring for apartments for low income people and for Black people, two parking spaces per residence. That makes, the parking spaces could easily cost more than 17,000 dollars each. And then there has to be parking at all the restaurants, and all the theaters and all the grocery stores and every place else. So, planners are willy-nilly requiring wildly expensive parking spaces that low income people cannot afford.

Eve: [00:20:53] Yeah.

Donald: [00:20:54] Can you think that one parking space is worth more than the median net wealth of the Black population in this country? And yet it is. You’re saying oh, well, you need 10 spaces per thousand square feet for a fast food restaurant. They have no knowledge of how much parking spaces cost or what it does to the looks of the building or who can eat there and things like that. So, I think that everybody probably looks at systemic racism through their own lens but I think in planning for parking there is a bias against low-income people in general and because Blacks are a lower income, it’s a it’s a bias against Black.

Eve: [00:21:33] Yeah, I think you’re probably right. So, I’ve been working with an architect in Australia who has been developing workforce housing for service workers like schoolteachers and firemen and policemen. I mean, the cost of housing is so high there they’ve been driven further and further away, which means there is a bigger and bigger requirement for them to own a vehicle, right? Which is expensive. So, they actually built a building with 30 units and every person who was going to buy a unit signed a petition, because this building was right next to a train station and a bike, and a bikeway right into downtown. And every person signed the petition saying they weren’t going to have a car. They were going to give up their car. And all they wanted was a bicycle. So, and the town planning, you know the town council there agreed that they could just build a small bike garage, which saved them a lot of money because they didn’t have to build those 20,000 or 30,000….

Donald: [00:22:33] As you point out, that if we have parking requirements everywhere, it’d be hard for low-income people to get an apartment close to where they’re going to work because the whole city is spread apart, because, to make room for the parking.

Eve: [00:22:50] That’s right.

Donald: [00:22:51] And I think that if a low-income person has to buy a car to get a job, which is mostly the case, that they have to support the car. They have to pay insurance, for repairs and everything else. So, I think we have systematically favored the car through parking requirements. It’s something that more cities are beginning to look at and maybe, I hope, some of your listeners will think hard and say, well, yes, it’s a house of cars, these parking requirements. What you asked a planner say, well, how was this parking requirement set? They can never tell you. They can tell you what it is when you go to the planning desk and say, I want to build a nail, you know, open up a new nail salon, they’ll tell you how many parking spaces you have to have. But they have no idea where that number came from.

Eve: [00:23:42] Interesting.

Donald: [00:23:43] Or how it was derived. How would you set the parking requirement for a nail salon? And you probably know much more about real estate than most urban planners.

Eve: [00:23:53] Yeah, it’s really tough and so, now with this pandemic, you know, we kind of got to take another look at mass transit as well. You know, how are people going to get around when they’re worried about catching a virus?

Donald: [00:24:07] Well exactly? I think so. I think that well, that’s a slightly different policy that I’m recommending but as related to it, that, at least in L.A. and I suppose, in Pittsburgh, that we were amazed at how little traffic there is during Covid when people are staying at home. You could drive anywhere in Los Angeles.

Eve: [00:24:30] Yes. Here too.

Donald: [00:24:32] You never would have gone there before because you’d know that the traffic congestion was so terrible. Say, we have a city of Long Beach, which is south of Los Angeles and adjacent to it, has express buses to UCLA, it’s about a 30 mile trip. And the schedule before Covid it was, it took about, I think, 90 minutes or something like that, at an average of 15 miles an hour on the freeway. And now, during Covid it was a twenty-seven-minute trip. And so, how are you going to maintain that? And one of the things I recommend is, what we already have is called hot lanes. Do you have these?

Eve: [00:25:19] Yeah, yeah. We actually have a dedicated busway which is fantastic.

Donald: [00:25:24] That’s what we need more of.

Eve: [00:25:26] Yeah, I know. I can get from downtown to the airport faster on the bus for $2.50 than I can possibly drive, and it drops me right out the front door and it’s really pretty fabulous.

Donald: [00:25:39] Well we have, we have these high occupancy vehicle tollways. There’s HOV lanes that solo drivers can buy into it, if they pay a toll. But there’s an incredible amount of fraud on them. Because we have to have a transponder if you use the lane and if you say that you have three people in your car, you don’t pay any toll. I’ve seen the estimates that 30 percent of all the solo drivers in the tollways are saying that they’re a three-person carpool. So, they pay nothing and that bogs down the HOV lanes because they don’t perform the way they should. So what L.A. is just about to try is to say we’re going to change it that everybody pays on the tollways except vehicles that have five or more passengers. So, if you’re a two-person carpool or a three-person carpool or four-person carpool, you still have to pay. Of course, you get a discount on a per-rider basis – four people in the car, each person only pays 25 percent of the toll. It would be very easy to police the requirements that there be five people in the car. It’s very hard for the authorities to put cameras to look and see, to check whether you actually have two or three people in the car. So, but if it’s HOV5, as they’re calling it, I think our freeways will begin to work really well and that buses will be able to go at high speed. If you could have an express bus from Long Beach to UCLA, and it might take half an hour instead of an hour and a half now.

Eve: [00:27:20] Isn’t that great?

Donald: [00:27:21] So that it’s more land economics. The streets, your very valuable land and we’re giving it away free. And any, any time something’s very valuable and you’re giving it away free there’ll be a lot of competition for it. That’s why there’s this terrible congestion. And that leads to air pollution, fuel waste, global warming. I think I’ve been invited to Pittsburgh maybe only once.

Eve: [00:27:47] Oh, we’ll have to invite you again.

Donald: [00:27:51] I really enjoyed it. It’s a wonderful town, of course, and I think a lot of people are moving there, from New York… I remember one time there was and interviewer from New York and I had a nice event with him and then later I wanted to get in touch with him. It turned out he had moved to Pittsburgh because it was so expensive in New York and he thought he got a much better lifestyle for the price in Pittsburgh.

Eve: [00:28:17] Yeah, it’s nice city. It’s small, but there’s one of everything. But listen, I have another question for you, because if I were an economist ,I’d be figuring this out and you probably already have. So, with all that extra toll money and meter money, what would you do with it? And what could you do with it? How much extra money? I mean, how could that make other people’s lives better, or people who walk or bike or?

Donald: [00:28:44] You mean how could removing parking requirements?

Eve: [00:28:46] No, no just increasing the cost of those valuable spaces and the freeways, like charging more in tolls and charging more at meters and..

Donald: [00:28:58] Well, I think the key to it is to tell people that if we install, you don’t have to install meters because you could pay for parking now with your cell phones. And some people, some new cars have that app right in the dashboard of the car, that will be much more common in the future that your car knows what is the price of parking, if it’s a new one, knows from the web how much parking costs, off-street and on-street, and it guides you to a good parking space. And so, I think it’ll be cashless for paying for parking in the future and frictionless and when you find a parking space you just touch a button on your dashboard and you’re paying for parking because the car knows where it is and what the price of parking is and then when you leave it automatically stops paying for parking. It’ll be more like making a long-distance telephone call in the old days when you just paid for how long you’ve talked, where you called. So it will be like charging just the market price, the lowest price that you could, the city could charge for one or two open spaces. When they do that, if they spend the money in the metered area, the people will understand the meters are really helping because, say in a business center, because many people from outside the district who are paying for parking. It’s not, it’s not a tax on the merchants. It’s like putting a cash register out at the curb and the neighborhood gets the revenue.

Donald: [00:30:38] I think there was one place in Pittsburgh they were thinking of running the meters in the evening and people said no, and the city offered to run an express bus to downtown for free if…with the revenue. And they, that persuaded people, well, maybe we should run the meters in the evening if it gives us a free shuttle bus to where we want to go. I think that people ought to think of parking like, on-street and off-street, like real estate and you ought to allocate it. Why do we have expensive housing and free parking? We’ve got our priorities the wrong way around. We’ve just been doing the wrong thing for 100 years. And I think that it’s catching up with us now and we have different issues. We have global warming to worry about and clearly, requiring ample free parking everywhere is not going to slow global warming. And I think that when you remove all street parking requirements, it’ll mean there’ll be a lot of land available for development.

Donald: [00:31:43] The New Urbanists recommend liner builders, I don’t know if you’ve seen them in Pittsburgh but it would, it’s an important issue here in California where there will be an office building in the center of a giant parking lot, or a mall in the center of a giant parking lot, and if you built housing or even offices around the perimeter and turned some of the required parking into the housing, the land is already assembled, there’s no assembly problem. There’s no remediation needed, and you wouldn’t have to build underground parking. So, I think that some of these giant parking lots, when there’s liner buildings built around the parking lot, as you walk down the sidewalk, it will look like a real city. It’s only about 25 feet deep but behind it is what’s left of the parking lot. But people will have to start paying for parking both on-street out off-street for this to work. I think there is a lot of land right where we want to have it, ready for development, especially for work-adjacent housing. I think if you want housing / job balance, having the, building housing right on the parking lot of an office building is a great way to get it.

Eve: [00:33:04] And so, what’s next for you? What are you working on? More parking or something different?

Donald: [00:33:12] Well, a couple of things. There is a thing I think I sent you. It was a new kind of zoning, zoning for land assembly. There was a problem in older areas, yes well, Pittsburgh is a good example, but L.A. has a lot of old development but there are a lot of very small parcels. Very small businesses, or small houses and now they’re near a rail transit stop and it’s very hard to assemble that land to build high density housing because of the hold-out problem. Everybody thinks that I’m going to be the key parcel that, if I’ll hold out for a high price to get my share of the of the gain when they build a 10-storey building on this land. But if everybody thinks that way, everybody holds out and it’s very hard to assemble land. Well, there was a new idea that was pioneered here in Southern California, that there was an area that had in Simi Valley that had very narrow lots but very deep because it had been an equestrian subdivision from the 1920s. So, each lot was about an acre or two but they were fairly narrower along the street.

Eve: [00:34:35] Interesting.

Donald: [00:34:36] They wanted to redevelop it but it was very hard to assemble the land because it had been with various families since the 1920s. And I think it was the mayor who thought of it, he said, well, let’s say if you have more than five acres, we’ll double the allowed density. And everybody began to think, well, you mean if I’m part of a land assembly the zoning will go up? And if I hold out it won’t? And so, people began talking to each other, saying should we participate in a land assembly? And then people began to fear them being left out. That if some of the neighbors were beginning to agree to sell their land, some of which was vacant, there were no housing on it, some of which were vacant, if they sell their land and I can’t be part of a new five-acre development I’ll not be able to get this high density. And within a year after developers, maybe like you, real estate dealers had tried to organize land assembly that had never happened, within a year they’d assembled all but about three pieces of property. And within two years later, they have two hundred and seventy single-family houses at very high density over this county where there had been 13 before. So, I think this is, it’s called graduated density zoning. The larger your parcel, the higher the density that’s allowed so that people will begin to cooperate. Should we cooperate? And that means that the landowners will get a good deal for selling the land. They know they’re selling for a higher-density developer. So, the people bidding for the land will have to offer them a price which is appropriate for land that will be rezoned as soon as the assembly happens. So that’s, it’s been spreading. Not as fast as I had hoped. But I think for older areas, for where the city wants land assembly, for more housing and certainly for more tax revenue, I think this graduated density zoning, as it’s called, is a good idea. So that’s one of the ways that’s really not parking oriented. But also, it’s easier to provide the required parking on a big piece of land, say, that any older buildings, like the one you’re in, couldn’t have been developed with a parking requirement because you can’t get the parking and the building onto the same small site.

Eve: [00:37:18] Yes, you can’t.

Donald: [00:37:20] So I think that this land assembly is, where the city wants it and where were the neighbors agree to it and they realize that, well, this is, what is the term, under-improved is that a term that’s used in real estate? You know where there’s just a shack on valuable land, but that shack is somebody’s home. And if they have to move, they’ll have to get something else unless they can sell their under-improved land for, to make way for a higher, higher density. And if the city provides, you know, requires some affordable housing and I guess they’re giving away an increase in density they can then require affordable housing in some of the units. So, I think there are some good ideas out there.

Eve: [00:38:12] Yes, definitely. So, I especially like the no parking requirement idea. And I hope it takes hold really soon. And thank you very much for chatting with me.

Donald: [00:38:24] Ok, it was fun talking to you and I’m happy to be reminded of my happy visit to Carnegie Mellon.

Eve: [00:38:32] Ok. Thank you so much.

Donald: [00:38:34] You’re welcome.

Eve: [00:38:35] Bye.

Eve: [00:38:36] That was Donald Shoup. He has a simple fix for the chaotic and varied parking requirements in U.S. cities. Remove the many, many pages of complicated parking regulations and replace them with one short sentence instead. No parking required. In the end, developers know best how much parking, if any, is needed. Parking, as Dr. Shoup points out, is an expensive use of our land. New York City, for example, has three million on-street parking spaces and 95 percent of them are free. If people paid for parking, those funds could be put towards making streets and sidewalks more attractive with more amenities for everyone. That sounds like a great plan to me.

Eve: [00:39:26] You can find out more about impact real estate investing and access the show notes for today’s episode at my website rethinkrealestateforgood.co. While you’re there, sign up for my newsletter to find out more about how to make money in real estate while building better cities.

Eve: [00:39:44] Thank you so much for spending your time with me today. And thank you, Donald, for sharing your thoughts. We’ll talk again soon but for now, this is Eve Picker signing off to go make some change.

Image courtesy of Donald Shoup