Strategic. Purchase profitable urban community shopping centers in partnership with Black entrepreneurs and community investors.

Building Black wealth. Providing a path for increased ownership opportunities of real estate assets.

Supporting Black talent. Providing opportunities to Black-owned businesses and opportunities for local community employment.

Scalable. Planning to provide investment opportunities in up to 16 service-oriented community shopping centers.

Black-owned. Project led and owned by a Black team.

Return. Up to 49% pro-rata share of cash flow and profit to investors.

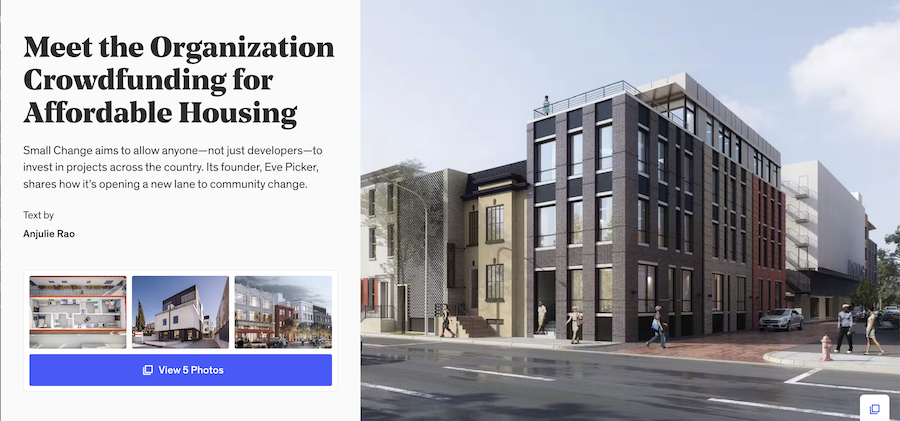

Chicago TREND, led by Lyneir Richardson, has launched a crowdfunding campaign to allow Black entrepreneurs, community residents and other interested socially-minded impact investors – with just a small investment – to co-own the Roseland Medical and Retail Center in Chicago, IL.

“Wealth is created by owning assets that generate revenue and appreciate over time,” says developer Lyneir. He wants you to own this shopping center right alongside him!

He’s looking for investors, small and big alike, just like you, on Smallchange.co.

This is not a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing is risky and involves the risk of total loss as well as liquidity risk. Past returns do not guarantee future returns. If you are interested in investing, please visit Small Change to obtain the relevant offering documents.

Image courtesy of Roseland Center