The blockchain is not as complicated as you might think. “Blocks” are just digital pieces of information and the “chain” is the public database where the blocks are stored.

The block

Each block (or digital piece of information) might include transactions, participants, dates, times or identifying information. This doesn’t necessarily reveal your name as the blocks use digital signatures much like usernames. Each block has a unique cryptographic code called a “hash”, created by a special algorithm, so that no two blocks can be the same. And a single block can store approximately 1MB of information.

The chain

The chain is then a number of blocks strung together. As a block of data is added, it not only becomes part of the chain, but it becomes publicly available. Information about the block such as when, where and by whom the block was added is available for anyone to see.

Distributed ledger

Each blockchain user can opt to connect through their computer to a node, often called a “distributed ledger”. This means the blockchain is “distributed” to their computer, not only providing a live feed of what is happening in that particular blockchain, but more importantly, distributing the information across a network of computers that might connect to it. Because blockchain is distributed in this way, there is no single, definitive account for a hacker to manipulate.

Security and trust

Each block is added chronologically to the end of a blockchain and contains its own hash as well as the hash of the block before it, making it extremely difficult to alter the contents of a block once it has been added to the blockchain. When a hash is created it is transformed into digital information. If this digital information is edited in any way, a new hash is created. Other security measures implemented in blockchain include tests for computers that want to join and add blocks to the chain.

Applications

The advantages of utilizing the blockchain include accuracy, cost reduction, decentralization, privacy, efficiency and transparency. Bitcoin, which we’re sure you’ve all heard about, is only one such application. Others being explored today include banking, healthcare, property records, supply chains, voting and smart contracts.

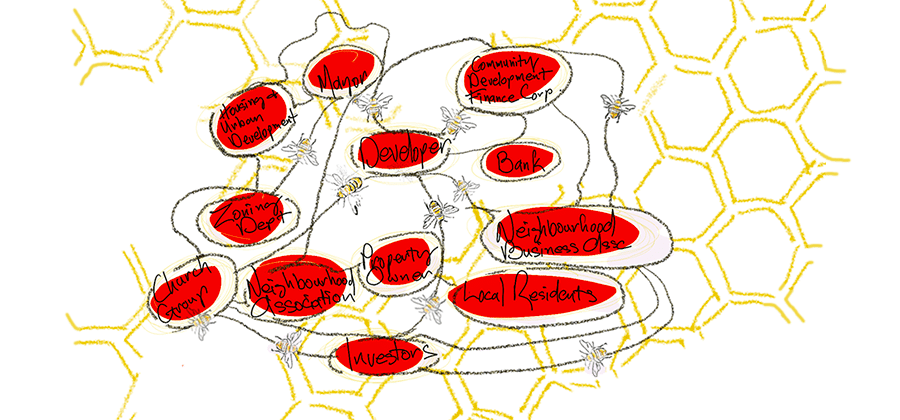

Michael Lee, a cultural planner and designer with an architectural background, has found a new use for the blockchain. He’s developed a web application called BLDGBLOX. The Bldg app is an online bulletin board which helps to turn community ideas into public action. The user-friendly interface of BLDGBLOX tracks information dynamically in projects created by anyone who wants to start one, as people use it and add to it. The information gathered in the blockchain created can be a useful way to track the impact of a particular project, thereby encouraging people to invest in projects that are impactful for their community. Michael hopes that the data gathered through BLDGBLOX projects will empower people to make more informed decisions. It’s an amazing example of blockchain being used as an organizing tool.

Listen in to my interview with Michael to learn more about how he wants to democratize the power of data.

Image by TheDigitalArtist from Pixabay