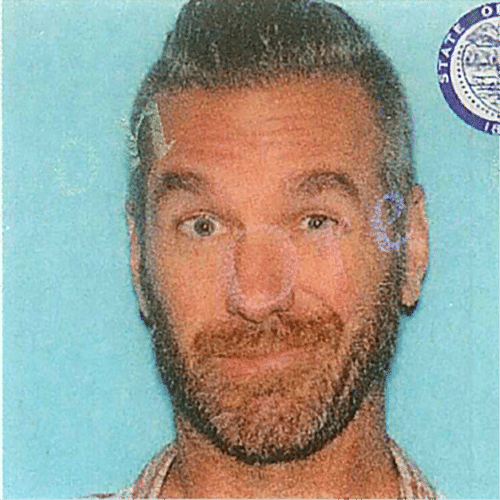

Kevin Cavenaugh is a rare developer. Left brain, right brain, head and heart all come to bear on his wildly creative buildings. He has carved out a special place for himself in the Portland real estate world. He has said, “I’m tired of mocha-colored, vinyl-windowed boring. I can’t change the fact that the streets are gray and the sky is gray. But the buildings?”

One recent project, Tree Farm, has 50 small trees in planters mounted on the outside of a six-story building, and his projects often have far out names like: Dr. Jim’s Still Really Nice, The Ocean, Burnside Rocket, Rig-a-Hut, Two-Thirds, and The Zipper. Two of his projects, Jolene’s First Cousin and Atomic Orchard Experiment, have units reserved for homeless people and social workers at reduced rates.

Trained as an architect, with a tour in the Peace Corps in Africa, Kevin was also a Loeb Fellow in 2007. After the Peace Corps, Kevin says, “I had my dog I brought back from Africa, and I bought a $300 little Chevy truck,” he says. “I grabbed a duffle bag, my skis, my golf clubs, and my dog—that’s everything I had—and I drove up I-5” to Portland. A newspaper ad got him a room in a shared house and a dishwashing job. Soon, he and his landlord/friend went in together to buy a house on NE Alberta Street for $16,000 financed on a credit card.

Kevin said in one interview that he creates projects that attract attention so the people will say “I want to live in that city.”

Insights and Inspirations

- “I’m driving the van” says Kevin. He doesn’t like to develop by committee. If you are on board, you’re in a back seat.

- You can download Kevin’s pro-formas, open-source, from his website. Check out each building!

- Kevin’s goal as a developer is to make a building that makes you happy to be there.

- He calls the monotonous buildings we are used to seeing, “pro-formas with windows”. He likes to use his right and left brain together to develop a building – iterations between design and the numbers. Both have to work.

- He’s been called ‘dangerously optimistic.’

- These days, more than right and left brain, he’s focusing on ‘head and heart,’ trying to weave “the good” into his projects.

- Of himself, he says “I’m not the smartest person in the room, but I’m the biggest risk taker.”

- Kevin loves his buildings. They are like his progeny. He never wants to sell them.

Read the podcast transcript here

Eve Picker: [00:00:15] Hi there. Thanks for joining me on Rethink Real Estate. For Good. I’m Eve Picker and I’m on a mission to make real estate work for everyone. I love real estate. Real estate makes places good or bad, rich or poor, beautiful or not. In this show, I’m interviewing the disruptors, those creative thinkers and doers that are shrugging off the status quo, in order to build better for everyone. If you haven’t already, check out all of my podcasts at our website RethinkRealEstateForGood.co, or you can find them at your favorite podcast station. You’ll find lots worth listening to, I’m sure.

Eve: [00:01:11] It’s busy, and my best intentions to get you a brand new podcast this week evaporated. But this is almost better. Here’s an interview I conducted with Kevin Cavenaugh last year. Kevin Cavenaugh may very well be my favorite developer. He has carved out a special place for himself in the Portland real estate world. His buildings are memorable escapes from the mocha-colored vinyl-covered buildings he so disdains. Forgotten buildings in forgotten neighborhoods, buildings that you and I would not look twice at, are transformed into little creative hubs and bright spots in Kevin’s hands. And now he’s bringing heart into his practice as well, setting himself the challenge of incorporating homeless housing or anti-gentrification into his projects. All with no subsidy and all providing a return to his investors. You’re going to learn a lot from Kevin so listen in.

Eve: [00:02:12] If you’d like to join me in my quest to rethink real estate, please share this podcast or go to RethinkRealEstateForGood.co, and subscribe to be the first to hear what we’re cooking up next.

Eve: [00:02:34] Hello, Kevin, I’m just really thrilled to have you on my show.

Kevin Cavenaugh: [00:02:38] Howdy, Eve. Thanks for having me.

Eve: [00:02:41] You are one bad ass developer. I’m really not sure where to start with this interview. I’ve seen so many tantalizing quotes by you, so I figured I’d start with those. Is that Okay?

Kevin: [00:02:54] Okay. Yeah, of course.

Eve: [00:02:56] The one I probably love the most is, “I do a bunch of weird stuff.” So what is it you do?

Kevin: [00:03:03] Oh. Boy, that’s a big essay question. So I guess for your audience, I’m educated as an architect and I became a developer only because I knew nobody would hire me to do that weird stuff. Well, and when I was working for an architecture firm, I was doing really boring stuff. And I realized early on that I was being hired at phase one as the architect, and the interesting thing is phase zero. Like I wasn’t deciding what the ‘it’ was supposed to be, what the program is. Here’s a piece of land, who gets to decide whether it’s going to be an apartment building or retail or mixed use. I wanted to decide that. That’s why I became a developer. Once that I realized that the developers weren’t necessarily smarter than me. They just control the money. And once I realized that it wasn’t their money, they just grabbed the important seat at the table. They asked around. I took some of the developers to coffee. I’m like, hey, is there any reason I can’t grab that seat myself? And they all said, no, you know, go for it. So that allows me to build my weird stuff. So I design and then develop and own and manage projects that I always wished somebody would hire me to do. If that makes sense.

Eve: [00:04:18] Yeah, it does. So there’s another quote which probably comes right off that. “I’m tired of mocha colored vinyl window boring. I can’t change the fact that the streets are gray and the sky is gray, but the buildings?” So is this your mission statement? How does this play out in your world?

Kevin: [00:04:37] Well, I’ve got like a dozen mission statements. It’s an ever evolving mission statement. But Portland, Oregon, the skies are gray and the city’s gray and it’s that’s great. I can’t change that. But I rail against institutional money. I never, I run away from institutional money. I run away from national franchise tenants. I want to be quirky and local. And actually, I want to prove that being quirky and local and colorful and not doing copy and paste buildings is just as profitable, if not more profitable than the mocha colored vinyl windows buildings. I don’t put vinyl in anything. As a trained architect, the design comes first.

Eve: [00:05:18] Vinyl is pretty offensive.

Kevin: [00:05:20] It’s so bad, it’s so bad. And it’s cheap and it makes sense in a pro forma if I’m going to sell the building. But because I don’t sell anything, I can do deeper dives on what I put in the building. I can paint The Fair-haired Dumbbell. That paint job on that building…

Eve: [00:05:36] Is insane.

Kevin: [00:05:36] Cost a half a million dollars. It’s the most expensive paint in the world. And I’m never going to sell the building, so I can make different decisions and I can add to the city skyline in a way that institutional money would never consider.

Eve: [00:05:51] Yes, and that is impactful, isn’t it?

Kevin: [00:05:54] I think so. I hope so.

Eve: [00:05:55] So there’s a final quote I’m going to read to you. “I just realized that I don’t have to play by the rules. It’s that simple.” How does that play out?

Kevin: [00:06:06] Real estate development is so easy and straightforward and simple. It’s almost, I’m never the brightest person in the room. The only thing I am is the person with the largest risk appetite, in the room. So once I took Francesca Gambetti to coffee and she was a client of ours when I was in the, at the architecture firm and I said, hey, how do you, what is a pro forma, how do you do what you do. And she laughs. She’s like, you’re already doing it, Kevin. You just bought a house in my neighborhood and I saw that you’re fixing it up and you’re selling. That’s development. That’s real estate development. You just have to shift the decimal point over. And instead of doing your house, do a little mixed use building. Or it could be an adaptive reuse. It could be new construction, but A plus B equals C, um, you know, hard cost plus soft cost plus land cost, you know, that’s that’s your total all in cost. And as long as when you’re done, throw a cap rate on it, it’s worth more than what it costs. You’re a successful real estate developer. So then my first question is like, that’s great, Francesca, what the hell’s a cap rate? So like, I was starting at zero. And after twenty minutes, I knew I knew everything. And then she emailed me her pro forma, which is the pro forma that I still use today, and all of my pro forma are up on my website open source. So people are downloading my pro forma from my products every day because if she gave it to me, I can pay it forward. It’s not complicated. It’s simple. And when people try to make it complicated, they mystify it in a way that keeps the layperson out of real estate development.

Eve: [00:07:40] Absolutely.

Kevin: [00:07:41] Which makes American cities dumber and uglier and more mocha colored.

Eve: [00:07:45] And doesn’t spread the wealth around. That’s what I deal with every day in crowdfunding. The fact that people don’t understand the special language that’s been developed for the developing incrowd, that just doesn’t have to be that complicated.

Kevin: [00:07:56] It’s not necessary.

Eve: [00:07:57] Yeah.

Kevin: [00:07:58] It’s so dumb. It’s just it’s you buying the neighbor house across the street that’s dilapidated and fixing it up and selling it. That’s real estate development. What you and I do, Eve, is no different. It just takes a little longer and it’s C for commercial instead of R for residential. But…

Eve: [00:08:14] That’s right, right.

Kevin: [00:08:15] Everything else is the same.

Eve: [00:08:16] Yeah. I can’t wait to download one of the pro formas. I’ll probably use it.

Kevin: [00:08:21] You’re welcome to it.

Eve: [00:08:22] There’s nothing worse than getting a pro forma that’s like 20 pages, 20 tabs, an Excel spreadsheet and you’ve got to work your way for every number, trying to figure out where it came from. That’s just too complicated for me.

Kevin: [00:08:32] Not necessarily. Mine’s one page. And the funny thing is, I go to a bank, with that pro forma that that you’re about to download, and it’s one page and I show it to a bank and I can get a 10 million dollar loan. So complex isn’t required. Banks aren’t demanding it. It’s just part of that language that we feel we have to create to keep the outsider out, which is just not helpful.

Eve: [00:08:56] Not at all. So going back to your quote about the mocha colored vinyl window boring, many of your projects have really both striking facades and pretty far out names like Atomic Orchard Experiment, Burnside Rocket, or Dr. Jim’s Still Really Nice, which I admit is my very favorite building.

Kevin: [00:09:18] That’s where I live. That’s that’s what I’m talking to you from, right now.

Eve: [00:09:20] Oh, that’s a beautiful building.

Kevin: [00:09:21] There are stories behind all the names. I don’t know that I want to tell you the stories, though.

Eve: [00:09:24] Oh, well, what are you trying to accomplish with your buildings? Let’s talk about that.

Kevin: [00:09:30] They are all experiments. They’re all just things that I want to do and I’m curious about professionally and sadly probably like you, it all is interesting. It all like when someone brings an opportunity to me, I look at it. I have such a hard time saying, no, I’m an actual addict. Like I, I can see fun in almost any project. And I go to my coworkers, like should we do this and they’re just as bad as me. They’ve never said no, no boss, don’t buy that property, don’t do that building. We are all in all the time. The names are funny. It’s just that if I told you that the names are so deeply personal to me and I found in the past that when I explain to somebody what a name means, they’re almost disappointed because the story that’s in their head or what they’ve kind of thought of is much more compelling than what I just told them.

Eve: [00:10:21] I have no preconceptions about who Dr. Jim is.

Kevin: [00:10:25] Dr. Jim Saunders is an eye doctor.

Eve: [00:10:28] Oh.

Kevin: [00:10:29] And he sold me a warehouse over on Southeast Ankeny Street. And I got really creative financing and I borrowed hard money for hit the down payment. He carried a contract so I bought his building without any money of mine. And as soon as I closed on it, a hard money guy reached out to Dr. Jim Saunders and said, hey, Cavenaugh has no skin in the game. I want to replace him. I want, the buildings worth more than you sold it for. I’ll pay you more.

Eve: [00:10:55] Oh. Eww.

Kevin: [00:10:56] A just as little end around. And I had bounced a check, my first payment to Dr. Jim bounced. So like, I was in a really vulnerable place. And Dr. Jim called me up and he’s like, Hey Kevin, like what are you doing. Like I like you. You’ve been, we’ve been talking for a year. We’re like, you put this together and like I believe in your vision. Don’t like, I don’t want to get calls like this. So he could have made more money. And he said he had other offers for more than than what I was paying him as well. And he kept honoring his handshake to me.

Eve: [00:11:30] He is really nice.

Kevin: [00:11:33] Yeah, he’s really nice. So ,that building, that project was called Dr. Jim’s Really Nice. Now, in the recession, I had to sell that warehouse because the bank put a gun to my head and I lost everything in the recession.

Eve: [00:11:46] Awww.

Kevin: [00:11:46] But lo and behold, eight years later, I bought another warehouse, a hundred year old warehouse, one more neighborhood over. The exact same program, that exact same phase zero that I talked about, I was doing. And when thinking of a name, I just I wanted to still honor Jim Saunders. So I named it Dr. Jim’s Still Really Nice. That’s the LLC of the building and it’s a single asset, LLC. Dr. Jim doesn’t know this building is named after him. I haven’t I haven’t talked to him in a while, probably should mention to him that I’ve given him props.

Eve: [00:12:20] Well, I think that’s a great story behind the name. So what are you trying to like, they’re all experiments, but I know I’ve been to some of these and I love your buildings.

Kevin: [00:12:32] Thank you.

Eve: [00:12:32] And I can see that they are, you know, experiments with a clear purpose. There’s got to be more than just I’m going to experiment with this building.

Kevin: [00:12:41] Yeah. Yeah. So there’s a couple different layers to that. When I first started, it was about left brain, right brain. Even before that, I think most buildings have too many cooks in the kitchen. I think buildings that we’re all drawn to and we all see have one dominant voice, one dominant vision who is in charge. And and it’s not a committee of designers or a community.

Eve: [00:13:07] Not a democracy, right.

Kevin: [00:13:08] It not a democracy. No. And I say that to my investors and I say that to other folks. I don’t collaborate. I don’t have any interest in collaborating. If you want to if you want to hop into my 15 passenger van, that’s great. Just you got to sit in the back. I’m going to I’m driving this van. I’m not sharing the steering wheel with anybody. And you end up getting these hopefully iconic, singular, visionary buildings that I don’t need to explain them to you. You as the observer or participant or tenant. You just get it. And you don’t know how I got there. You don’t care. You’re just really happy to be in the building. That’s the goal.

Eve: [00:13:41] Right.

Kevin: [00:13:41] When I started, the first layer was left brain, right brain. So a product always starts with the design. And then I instantly toggle over and do a pro forma. And if the numbers don’t work, then I crumple up the paper and start with a new design. So it has to be design first and then the numbers. But the numbers can’t be ignored because there’s a lot of architects who become developers and just done one project and it’s an ode to their ego and then they can’t do it again because all of their money is sunk in the building. It’s not really a successful financial deal in the bank. The bank says next time, like, nah, I’m not that interested in giving you the million dollars because that wasn’t very pretty the first time. So the numbers have to work. But the vast majority of our peers, Eve, it’s only the numbers. So I view those mocha colored vinyl windowed buildings. I call them either Greavy buildings or I call them pro formas with windows. And I look at them. I think I know exactly what the numbers look like in that, because it’s just a pro forma that the developer is only tasking the architect to do the bare minimum to reach this ROI, to reach this return, to reach to reach this number.

Eve: [00:14:53] Right.

Kevin: [00:14:54] And the funny thing is. None of our buildings are maxed out. So if a developer says, hey, I know I can put 100 apartments on this site, so they hire the architect and the architect has no option of building designing 90 units. When a 90 unit building might be significantly better to the city skyline, to the streetscape.

Eve: [00:15:12] Right.

Kevin: [00:15:12] There are no dog units with their 90 units, but if there’s 100, there’s going to be some dog units. But the developer doesn’t care. He or she just wants the 100 units. So toggling back and forth between my left and right brain is all about making sure the design is always front and center and it just has to make enough money. And then I pull the trigger, then I go for it. The tricky thing is that the last layer to that equation, what makes a building compelling or not, is about social repair. So now it’s more about head and heart instead of just staying left brain, right brain all on my head. Now I look around the city and I see homelessness or I’m doing a project that supports social workers. I’m doing a project that supports 18 year olds aging out of foster care, which have a higher proclivity to become homeless. I tried to do a reverse gentrification project, which isn’t actually a thing, but in the office we call it gentlefication. So how do I how do I develop in a neighborhood that’s turning without displacing anyone who’s already there? So these are the more social repair elements that I’m trying to lean into, which is super fun, but hard.

Eve: [00:16:22] Very difficult. Yeah. Oh, that’s really interesting. So these projects I mean, I’ve seen you do some pretty remarkable projects, which includes homeless housing and in neighborhoods that no one else have looked at really before. Are they making you money? Are they making your investors money?

Kevin: [00:16:42] They are. Jolene’s First Cousin is my first attempt to tackle homelessness, and it’s up and running. It opened last summer and we cut Q4 distribution checks last month.

Eve: [00:16:59] That’s amazing.

Kevin: [00:16:59] And it made five percent from the crowdfunded equity. It made, I think seven percent for the long term tranche of investors. I raised three hundred grand of crowdfunding and three hundred grand of accredited investors. And there’s not one dollar of public money in that project. And I’m super proud of that.

Eve: [00:17:18] Amazing. That’s amazing.

Kevin: [00:17:20] It’s fun.

Eve: [00:17:21] Congratulations.

Kevin: [00:17:22] Thanks. And the performance online, go ahead and take it. And I’m I’m breaking ground on Jolene’s Second Cousin and I’m buying the land for Jolene’s Third Cousin. So I’m just going to pepper, these nestle into neighborhoods. I don’t like Pruitt-Igoe or Cabrini-Green. I don’t like when thousands of poor folk are crammed into a building. That’s a great way to not break the cycle of poverty from generation to generation. So each Jolene’s Cousin only has like a roughly a 12 bed SRO plugged into it, like a 12 bedroom apartment, like a flophouse, and the tenants pay rent. It’s just that it’s super, super, super cheap rent. And there’s usually a subsidy for that rent. That’s not my, I’m not involved in that. I just provide the …

Eve: [00:18:11] What’s the what’s the rest of the building. How do you make that pro forma work?

Kevin: [00:18:17] It’s internally subsidized. So, Jolene’s First Cousin has three retail spaces. It has a hair salon, a coffee shop and a bakery. It has two market rate apartments that are very expensive and it has the SRO, the homeless housing unit. So when all six rents are added together, it’s enough to spin off a profit. And the other fun thing is, it’s allowed by a right. So I didn’t have to do any special entitlements to get it. In Portland, you have to go and present to the neighborhood association on any project. Because it’s a law by right, you don’t have to do what they ask, but you just have to be a good neighbor and be transparent. This is the first neighborhood association I thought I was going to go in front of where I was going to get rotten tomatoes thrown at me. Because here I am, I’m bringing homeless in. I mean, there’s a single family house right next door and I presented it and I kind of stood back and waited and there were no questions and there were no tomatoes. And then I asked a question, how do you guys, what’s your take on this? Like, how do you feel about bringing homeless into your neighborhood? And then a woman in front said, well, once they lived there, they’re not homeless anymore.

Eve: [00:19:23] And they’re probably already in the neighborhood, so giving them a home…

Kevin: [00:19:27] Exactly. And then another neighbor said, with 11 bedrooms, like, we’re going to know their names. It’s going to be like Suzy and Jim and Frank. And if it was 100 units, we probably would be pushing back Kevin. But there’s 11. So they were in total support. And they’re it’s been wonderful.

Eve: [00:19:45] That is wonderful. And, you know, I think it’s vastly different than it might have been five years ago. I think homelessness and affordable housing is now on everyone’s mind. And it’s a real shift. But, you know, what about the two market rate units? How do they feel about the SRO unit right next to them?

Kevin: [00:20:02] That’s a great question, because there was so much speculation in the papers, on blogs, like like Cavenaugh’s an idiot. Like no one’s going to rent those. Nobody’s going to want to, like, be paying 1,800 bucks a month living like next to guys who used to be living in sleeping bags out in front on the sidewalk. And my response was like, well we’ll see, you know, like all of my products are all experiments. It’s a question. There’s only two units. My guess is there are two people who will love being part of this. And lo and behold, they rented out in about 20 minutes.

Eve: [00:20:40] Oh, that’s fantastic, Kevin.

Kevin: [00:20:41] There’s a huge backup. Yeah. Backup for people who want them when they become vacant again.

Eve: [00:20:46] Are you sure you won’t partner with anyone? Because I want to do a project with you.

Kevin: [00:20:52] Just take it…

Eve: [00:20:52] I would like to be in the passenger seat, not the back seat.

Kevin: [00:20:56] You’re welcome to be in the passenger seat. I do. I do talk about that. I said it’s not a pretty ride. It’s usually scary, but I always arrives safely at the destination.

Eve: [00:21:08] Oh, it really sounds wonderful, sounds wonderful. Okay.

Kevin: [00:21:10] But you know exactly how to do this, Eve. You should just take my plans and my pro forma and build it in Pittsburgh.

Eve: [00:21:18] Yeah, I should. I’ve been thinking about it for a long time, actually. I have one in mind, but it’s a lot of fun what you’re doing and really impactful. So, you did mention crowdfunding. So, you know, I first became aware of your work when I started to build Small Change, my crowdfunding platform. And you had launched a Regulation A offering, which, if I’m remembering properly, may have been the first of its kind for one of your buildings in Portland.

Kevin: [00:21:42] Yes.

Eve: [00:21:42] The Fair-Haired Dumbbell. And what was that about? Why did you do that?

Kevin: [00:21:47] Good question. I don’t, I didn’t realize it was the first until we were done and then my lawyer, I chose this lawyer who was recommended to me because he was an expert in crowdfunding, all the hoops that he had to jump through. And when we were done, it took me a year and a half to to get through the SEC regulatory framework. He, on the phone is like, oh, my God, congratulations. We’re so excited. This is our first one. Wait, what? Like you’re the expert? What do you mean? Like this is your first one. He’s like, no, this is everybody’s first one. So,

Eve: [00:22:20] Wow.

Kevin: [00:22:21] It was a big deal. It was the the first new construction. I think there was one prior to me, construction that the Fundrise brothers put together.

Eve: [00:22:29] Yes. I remember seeing a photograph of the paperwork they had to submit, which was about three feet high.

Kevin: [00:22:38] Yeah. Yeah.

Eve: [00:22:39] And just, um, just for listeners who are not aware, Regulation A is an offering that lets anyone over the age of 18 invest. It requires really writing almost like a mini IPO and submitting it to the SEC and getting their approval before you can launch and raise money. Right?

Kevin: [00:22:54] Exactly right. Yeah. And it’s it’s a lot it’s a it’s a heavy lift.

Eve: [00:22:59] It’s really not worth it for, you know, anything much under five or ten million dollar raise. It’s too much work. Right?

Kevin: [00:23:05] I raised one and a half million dollars.

Eve: [00:23:07] Oh!

Kevin: [00:23:08] I don’t know that I would do it again for that amount, but I want to do it again because the idea of it is so profound to me and I know to you too, Eve. So, I’m legally not allowed to talk to my mailman or my kid’s teacher about a very lucrative development deal that I’m working on. They’re not accredited investors. They’re not already wealthy.

Eve: [00:23:33] Right.

Kevin: [00:23:34] And part of the social repair that I’m working on is the wealth gap in America. It’s broken, it’s distorted. It’s not sustainable in the long term. It’s not sustainable today. So when I decided to dip my toe into the crowd investing pool, it was purely to allow mechanics and school teachers and librarians to own a 17, 18, 20 percent, 10 year IRR building with me. Right. Internal rate of return, a really lucrative investment. Like my wife has a 401k and she puts her money in a mutual fund. And that’s all she, the options to her are different than the options to somebody who’s on the 17th fairway of a country club golf course talking to his buddy about deals.

Eve: [00:24:21] And many people don’t have a 401K at all. They’ve just got the bank with less than zero percent interest.

Kevin: [00:24:29] Exactly. So it was important to me, just ethically and profoundly to do this, even though it was, it would have been so much easier to just tap some rich guy’s shoulder and say, hey, I need 1.5 million, that’s the gap to get this product off the ground. Instead, I took a year and a half and people for as little as 3,000 dollars now own the Dumbbell with me. And they’ve been getting paid from day one, eight percent.

Eve: [00:24:50] That’s fantastic. So, yes, since then, regulation crowdfunding has come into play, which is, would be much easier for you. But I have yet to convince you, yet.

Kevin: [00:25:00] Well, I’ve done two other crowdfunding vehicles on the homeless housing project. I did raise 300,000 dollars that way…

Eve: [00:25:08] Through a state vehicle, right?

Kevin: [00:25:10] Yeah. State only. And that was unaccredited. And then on my Tree Farm Building. I like that one for your listeners…

Eve: [00:25:18] What is a Tree Farm Building?

Kevin: [00:25:21] You got to go my website and see it, but it’s like it’s self-explanatory.

Eve: [00:25:27] Okay.

Kevin: [00:25:29] But I raised two million dollars that way, but they’re more accredited and I don’t want to holler from the rooftops about that. But it is legally, it’s another form of crowdfunding.

Eve: [00:25:39] Well, we just had a breakthrough on our site. We raised almost 900,000 dollars through Reg CF.

Kevin: [00:25:45] Wow.

Eve: [00:25:46] For a project in the Berkshires. And the issuer was the most pleased when the local librarian made an investment.

Kevin: [00:25:53] Yeah.

Eve: [00:25:54] He was just delighted. And I mean, that’s really the point, right? That’s why I do it.

Kevin: [00:25:00] It democratizes real estate investing.

Eve: [00:26:02] Yeah.

Kevin: [00:26:05] I understand why there are fences up that keep the shitty developers from bilking Mrs. McGillicuddy from her retirement. Like there should be there should be rules and laws against that from happening. So so lowering the bar for me to talk to Mrs. McGillicuddy can be scary, but it’s still a pretty damn high bar. I just like that I can jump through some hoops and you can jump through some hoops and Mrs. McGillicuddy can invest in a building.

Eve: [00:26:32] Well, you can actually, under Reg CF talk to her, but you can’t tell her the terms of the offering. That’s got to be on a registered funding platform. But you can say to her, we’re doing a project and it’s around the corner from you and you can invest. If you go to this funding portal, right?

Kevin: [00:26:49] Yeah, yeah, I love it.

Eve: [00:26:51] Yes, I love it, too. Okay, so so you’ve gone from getting your architecture degree, to joining the Peace Corps, to far out real estate developer. And told us a little bit about how you did that. And what’s the biggest challenge you’ve had?

Kevin: [00:27:11] Mmm, well I lost everything in the 2008-10 recession. That was difficult, but, it I mean, on paper, that should be the most challenging. I lost everything. On a Thursday, I had a net worth of four million dollars. And then a month later on this day, on a Thursday, I was a million dollars underwater. And that should be bad. That should be difficult. My buddy claims that I have HSP, which stands for hyper serotonin production, which isn’t a thing, but I didn’t even know at the time that I was getting punched in the face by the economy. Every day I would wake up like, Okay, I guess this is the puzzle and I like puzzles and I know you like puzzles and just everything.

Eve: [00:28:03] Yes.

Kevin: [00:28:03] All of our products are puzzles and it’s just another puzzle. And I got to figure this one out. So I should have probably been more devastated by it, but I was too dumb to know that I was, you know, in a hole.

Eve: [00:28:13] Oh, I don’t know that that’s forward looking, right?

Kevin: [00:28:18] Yeah, I think that my internal wiring is probably such that I, like my wife calls me dangerously optimistic. So there are probably things where I should have been more concerned or realized that I was on the ground, but I just didn’t even realize it.

Eve: [00:28:34] Wow. So, you allowed to talk about your next project. What are you working on now?

Kevin: [00:28:39] Sure. This is a fun one, so I never want to sell anything.

Eve: [00:28:44] Why is that? Is it because you love your buildings too much?

Kevin: [00:28:49] Yeah, it’s like selling my progeny. Like, I spent so many, like I lie in bed for I go to sleep and I’m like building. I close my eyes. I’m building the building in my head and by the time it’s drawn, I’ve already built it 100 times in my head. It’s my baby. Like in the 2008 recession, now a lawyer owns the Burnside Rocket. And I did, it’s LEED Platinum. There’s a geothermal open loop heat pump under the under the building, although all the water is, you know, I have tapped into a 10,000 year old aquifer for all the potable water. It’s it’s a crazy fun experiment. And now some like, you know, kind of a knuckleheaded lawyer who doesn’t care about that, owns that. It’s just an asset. And he views it differently than I view it. So I don’t want to sell. Was it Monday, my most recent project? I’m buying a house on a big lot out in what’s called The Numbers of Portland. It’s a pretty trashy area. It’s no sidewalks, deeper poverty, houses without foundations, double wide trailers. It’s it’s it’s rough, but it’s also where all the young families are moving because they can buy there. Because the house prices have just gone through the roof here. So we all understand that in five, 10, 20 years, it’s going to be a place you want to be. It just not a place, now. You’re on the bleeding edge of gentrification. So, I’m actually going to buy this house for 265,000 dollars. And on Zillow is worth 100,000 more than that. It wasn’t on the market. Someone just called me up and I’m going to split the house off and probably give it to someone else to fix up and keep that. I don’t need the profit from that. Someone else can go get the profit, but all they want is the land and the rest of the land, the, a guy named Eli Spevak is a developer in town. And he does forward thinking policy. And Portland has some wonderful density promoting policy and Eli’s work to change all the zoning for every single family house you can now build fourplex on. You’re allowed by right to build a fourplex on it, in the entire, everywhere in the city. And this lot is such that I could build 12 houses if I wanted to. I don’t want to own rentals out in The Numbers. So what I’m going to do is I’ll fit seven. There will be seven two bedroom cottages, two story, two bedroom. Little front porches, you’ll walk down a path and they’ll spin off to the left and right. And these will cost 200,000 dollars each but be worth 300,000 dollars each. And I will sell them off for two hundred thousand dollars to first time homebuyers who qualify. You have to be poor, whether it’s a perfect partner with Habitat for Humanity or some agency to identify who the buyers are. But held against the deed of the house, if you buy this for 200 and that’s worth 300, that’s great, but has to always be owner occupied. And if and when you sell it, you have to sell it at two thirds of the appraised value. So it has to always be affordable. So if you sell it for, if it’s worth 600,000 grand in a decade…

Eve: [00:31:52] How are you going to track them?

Kevin: [00:31:55] Just put a covenant against the deed on everything.

Eve: [00:31:57] Wow, and are you going to break even on this?

Kevin: [00:32:01] I’ll probably make 10 grand per house, so I’ll make 60 grand and it’s not enough to, you know… Yeah, I’ll break even. It’s it’s a deep experiment. The other projects, I’ve got 21 other projects and since I keep them ,they all spin off a little bit of money to me. But you know, it’s been a decade since the last recession and now I’ve got those 21 projects, 14 of them are spinning off money and I now make enough passably that I don’t need each project to work.

Eve: [00:32:39] Yeah, yeah.

Kevin: [00:32:39] If it breaking even is is a fine. Not everyone do I want to do that with, but…

Eve: [00:32:43] Interesting.

Kevin: [00:32:43] This feels fun. I’m also this week I’m putting an offer in on Jolene’s Third Cousin, so I’m keeping that going. So there’s, there’s no lack of fun stuff. I’m breaking ground on an apartment building where 20 percent of the lofts are being held aside at 60 percent of median family income for, I mentioned before, 18-year-old aging out of the foster care system in a really great neighborhood. Most see their options for living are way out in The Numbers, not near jobs, not in your transit, not near opportunities. So that’ll be fun.

Eve: [00:33:19] It all sounds fun. And I’m really jealous.

Kevin: [00:33:22] I just I’m just I virtue signal like nobody else, you know, that’s all I’m doing.

Eve: [00:33:28] So I’m going to ask you one wrap up question and that’s what’s your big, hairy, audacious goal?

Eve: [00:33:35] Oh, that’s a that’s a great question, because I just spent the month of January vacationing and usually the big, hairy, audacious goals happen when you’re not in your 9:00 to 5:00. You have to step outside of your life to to have them kind of allow your your brain to accept them. So, my youngest of three is a junior in high school, and in a year and a half, I’ll be an empty nester. And I have been courted by lots of other cities. Cincinnati, Honolulu, Denver. And I’ve always said no because I can’t do what I do it unless I am embedded in that city. I do a lot of micro restaurants. I find that food is a great inroad into a neighborhood. It’s a great, micro restaurants are like a a variation of the food cart. I understand the business model. I need to live in Pittsburgh to know who the sous chefs are, looking for a space that can afford 25 or 30 grand if they call their uncle and their neighbor and they can cobble together some money and open up a restaurant. I’ll never know that person without living in Pittsburgh.

Eve: [00:34:43] Mm hmm.

Kevin: [00:34:44] So in a year and a half, I know that I’m start taking the show on the road. And to kind of continue the the virtue signaling theme. I am a fifty three year old white man. And the vast, you know, this Eve, good God, the vast majority of developers look like me. Maybe 10 years older, maybe 50 pounds fatter, and it’s just it’s a caricature.

Eve: [00:35:10] Mm hmm.

Kevin: [00:35:10] But it’s true. And there’s no license you need to be a developer. There’s no special credentials or, you just need to have knowledge and you need to be invited into the room. You need to have access to the 17th fairway, the country club, and that’s a broken system. So, as I go into cities like Honolulu or Tucson, I’m thinking of Detroit as well. And I create branches of Guerrilla, and I go and I drop myself in for three months at a time. I want everyone that I hire to eventually run the show. To be native Hawaiian or Latino or African-American, and when I leave, I’m gonna drop the keys off to the company, to the next generation, a developer that looks nothing like me because that doesn’t happen to them. When I lost it all, it took me about a minute with my 505 credit score to get a loan for a million dollars for my next project.

Eve: [00:36:09] Mm hmm.

Kevin: [00:36:09] That’s not OK. There are people who are much more deserving and I didn’t question it at the time. I was just so happy that I can merge back into traffic and start developing again. Now, we all realize that there are people at that same bank getting rejections that were much more deserving of the money. They just didn’t look like, I look like I’m good at tennis and golf. I look like, I have the gift of gab. That helped me get that million dollars and my face more than anything else. I had a 505 credit score. That’s offensive. That’s really, really bad. And only now am I realizing that other people need to just be handed opportunities and they need to have hutzpah and they need to have tenacity, the way that I know you have, Eve. I mean, it’s more about personalities than skill. I can teach you skill. I can teach you how to do certain tasks, like just the way that Francesca Gambetti taught me.

Eve: [00:37:04] It’s about sticktoitness, too, isn’t it?

Kevin: [00:37:07] Oh, my God, yes. If you don’t have a risk appetite and when I’m interviewing the next generation in Detroit, I want to know all about you as a person. I don’t care about whether you know Excel. I don’t care about where you went to school. I need to know what happens when you get punched in the face.

Eve: [00:37:21] Yeah.

Kevin: [00:37:23] And I can’t wait ten years from now, to walk away from these branch companies and hand the keys off to the next generation and change the face of what development looks like.

Eve: [00:37:32] That’s an amazing goal. And I really appreciate you taking the time to talk with me. I’m totally in love with what you do, Kevin, thank you so much.

Kevin: [00:37:43] Thank you. It’s fun.

Eve: [00:37:56] You can find out more about this episode or others you might have missed on the show notes page at our website RethinkRealEstateForGood.co. There’s lots to listen to there. A special thanks to David Allardice for his excellent editing of this podcast and original music, and thanks to you for spending your time with me today. We’ll talk again soon, but for now, this is Eve Picker signing off to go make some change.

Image courtesy of Guerrilla Development/Kevin Cavenaugh