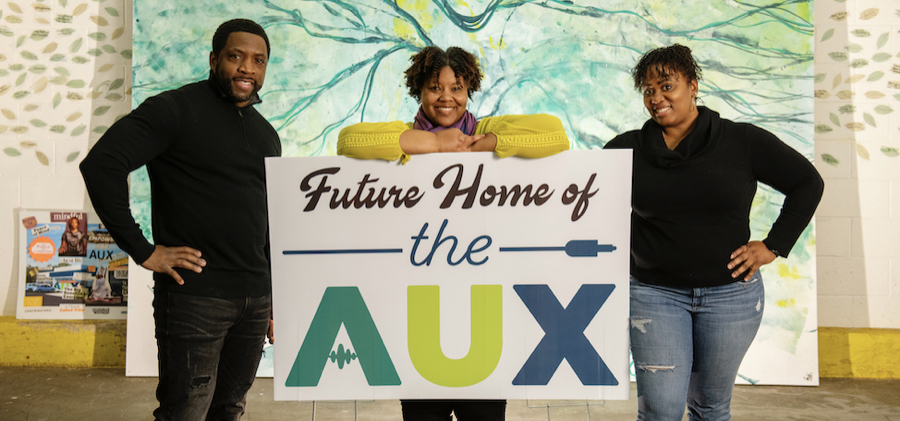

There’s a real estate project underway in Evanston, Illinois, and it’s called The Aux. Led by a diverse team, it represents much more than just the revamping of a 16,500 square foot vacant factory building. It represents the aspirational hope of a community.

Not only does the community plan to fully renovate the building into a wellness hub, they plan to populate the space with local, black-owned businesses including an award-winning chef, a laundry cafe, private offices and co-working space to name a few. Space is also planned for pop-up businesses coupled with entrepreneurial training programs in order to provide accessible marketplace options for growing new businesses.

The instigator, a non-profit, assembled a co-developer team of local leaders. They’ve decided to take on an even bigger challenge than this renovation. They are planning real community ownership. Every investor will become an owner with voting rights.

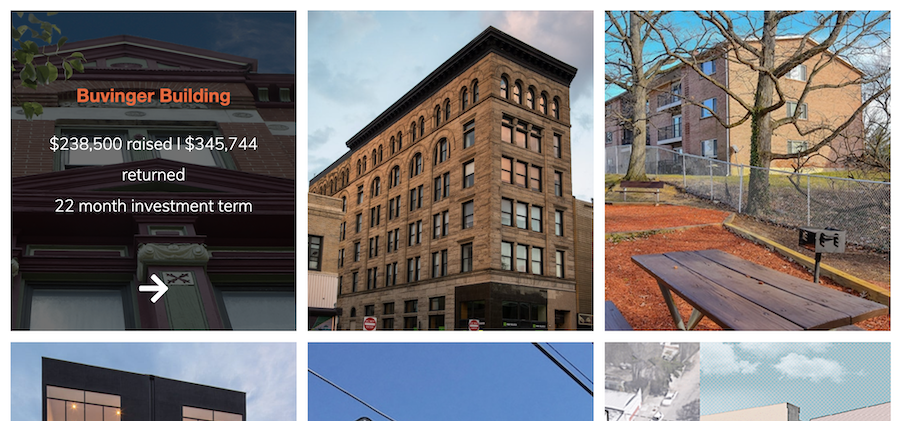

If you’re interested in supporting real estate projects that make a difference, look no further than Small Change, where The Aux is raising funds through a crowdfunded community round. Anyone who is 18 years old or older can invest here.

This is not a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities. All investing is risky and involves the risk of total loss as well as liquidity risk. Past returns do not guarantee future returns. If you are interested in investing, please visit Small Change to obtain the relevant offering documents.

Image courtesy of The Aux Evanston