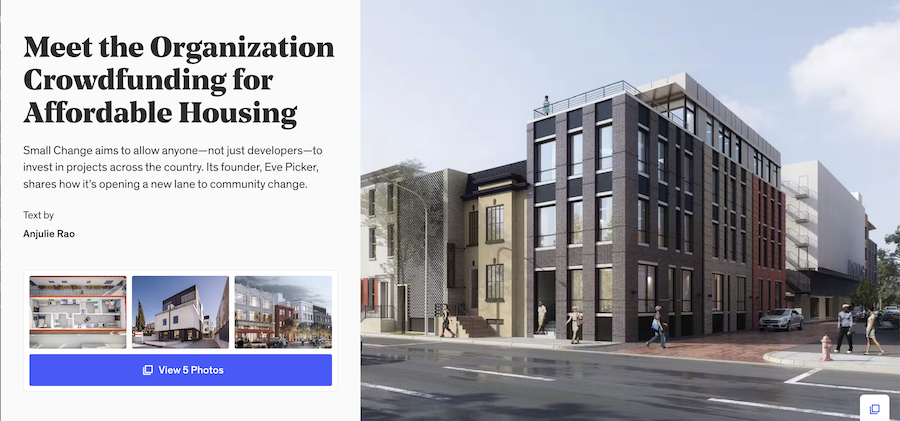

“Meet the organization crowdfunding for affordable housing” writes Anjelie Rao for Dwell magazine. “Small Change aims to allow anyone—not just developers—to invest in projects across the country. Its founder, Eve Picker, shares how it’s opening a new lane to community change.

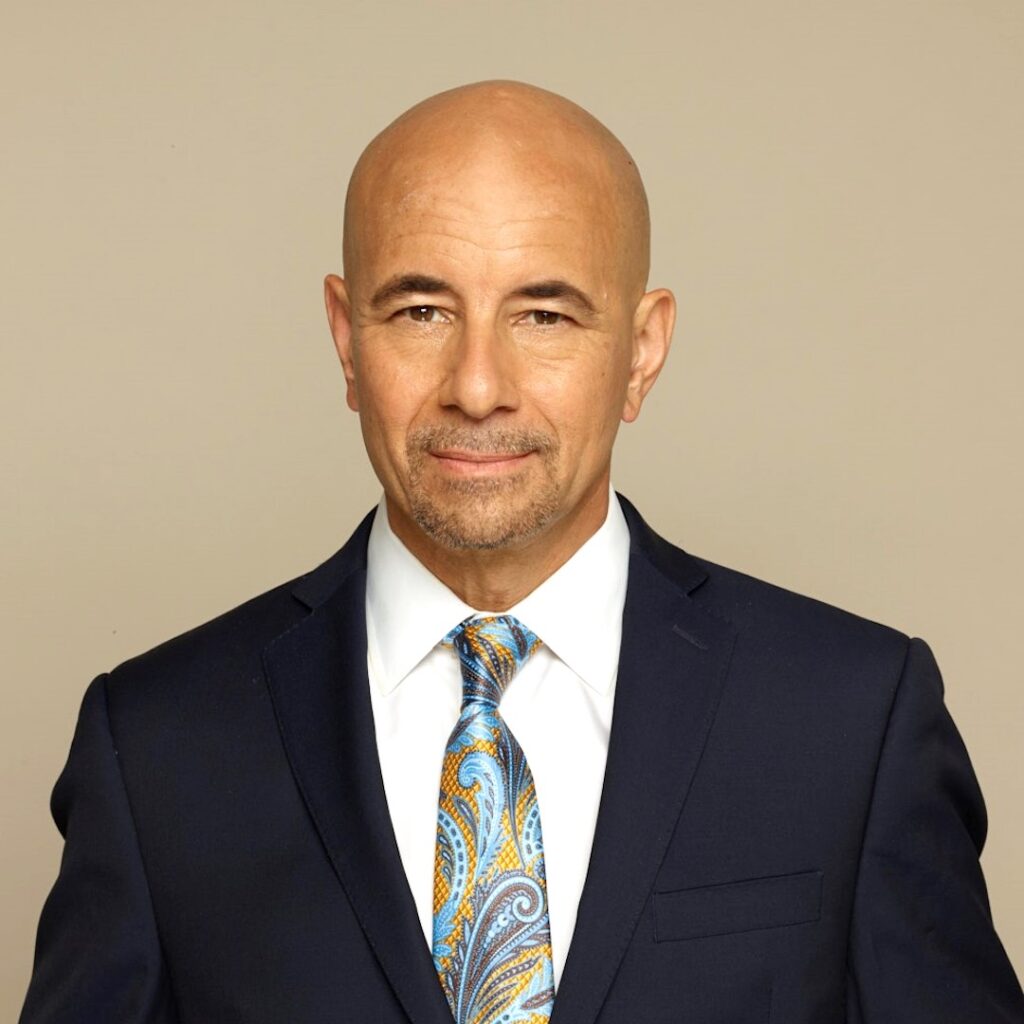

Real estate investment hasn’t always had the best reputation. House flipping, gentrification anxiety, and opaque LLCs have characterized a popular perspective on the industry. But Pittsburgh-based Small Change is a young company seeking to democratize the field and shift who participates in real estate investment—and how. Founded and led by architect-developer Eve Picker, Small Change has become a platform for minority and female developers, among others, seeking crowd-sourced funding to get smaller-scale projects that have positive impacts on their communities off the ground.

Crowdfunding’s heyday was born from ArtistShare, Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and their ilk operating under the premise that anyone should be able to invest in a good idea. But Small Change and other crowdfunded real estate platforms were facilitated by former President Barack Obama’s 2012 Jumpstart Our Business Startup (JOBS) Act and subsequent changes to Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations, which allowed non-accredited investors (whose net worth and income are relatively low) to invest relatively small amounts of money into businesses. For real estate, this meant that anyone, with any income or net worth, could invest in eligible commercial or housing projects and receive returns on the project’s success; developers can raise up to $50 million from crowdfunded sources. While some projects featured on Small Change are for accredited investors only, many are open to everyone.“

Read the whole story here!