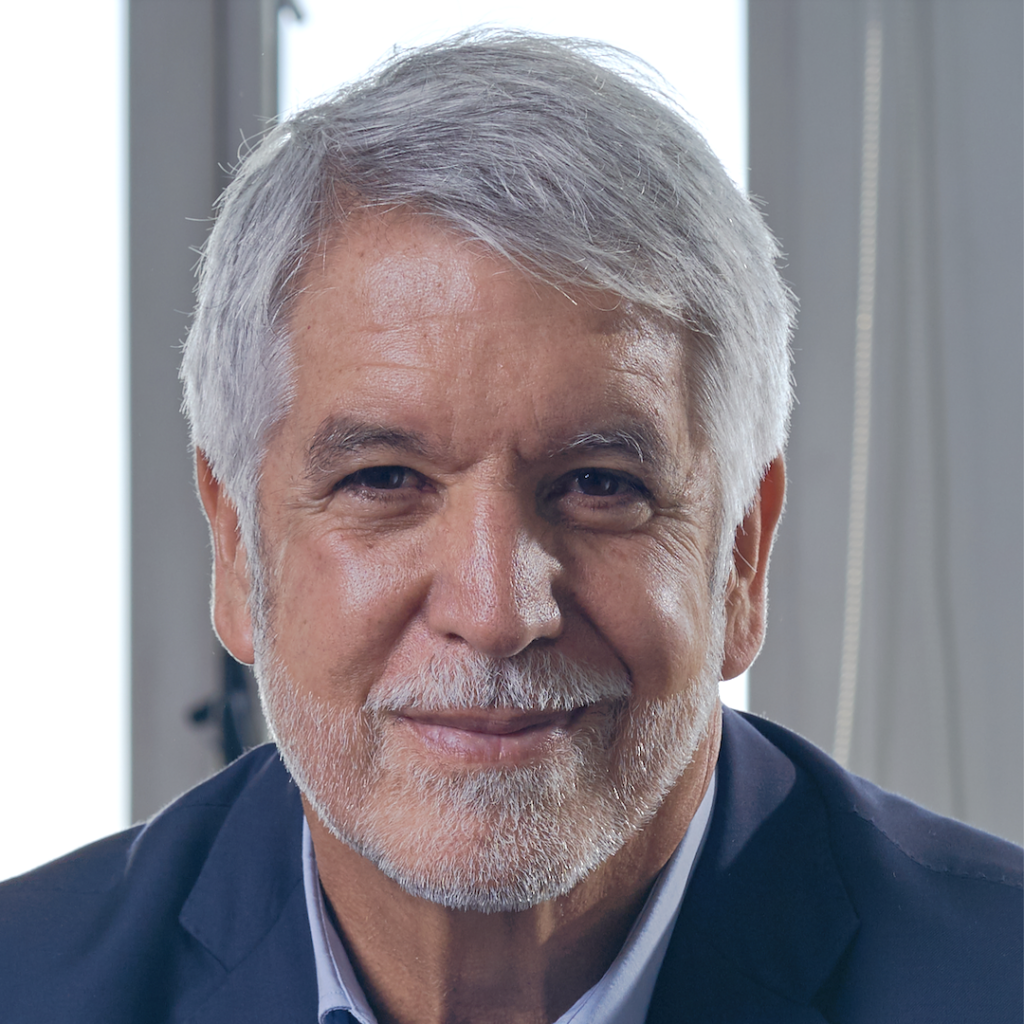

For the second year running GlobeSt. has made me a winner!

GlobeSt. has been recognizing the growing number of women in commercial real estate for their excellent professional achievements for over 30 years now through the “Woman of Influence” awards. The categories are broad. This year I’ve been included in the PropTech Executive / Innovator group of just seven women.

All credit to GlobeSt. for trying to turn the tide. We need what they want, and that is to recognize that both men and women are capable of amazing things. I’m eagerly awaiting the day that these awards will be renamed – from “Woman of Influence” to “Person of Influence”.

You can view the class of 2024 here.

Thank you GlobeSt!

Image courtesy of Eve Picker