“Co-housing communities are not communes. Residents do not give up financial privacy any more than they give up domestic privacy. They have their own bank accounts and commute to ordinary jobs. If you were lucky enough to grow up on a friendly cul-de-sac, you’re in range of the idea, except that you don’t have to worry about your child being hit by a car as she plays in the street. A core principle of co-housing is that cars should be parked on a community’s periphery” writes Judith Shulevitz for the New York Times.

Modern co-housing came about as a work/life solution. One of its pioneers was Hildur Jackson, an activist whose passion to solve the 1970s women’s dilemma between full-time work and being isolated and dependent as housewives, inspired her to cofound one of the first Danish co-housings in 1972.

This first attempt was a six-family “living community” on an old farm in Copenhagen. Six houses were built around large open spaces with the old barn converted into a common house. The families shared a large vegetable garden as well as maintenance tasks. Hildur recalled never feeling isolated in the 20 years she lived there and mused that her children grew up with 12 parents.

Co-housing soon spread throughout Scandinavia and the world. Today there are over 165 co-housing communities in the United States. Most have common areas for social interaction which might include a shared kitchen, a pool, a workshop, community garden, or rooms for meetings or celebrations.

Beyond the shared workload, there are clear advantages to co-housing:

- Affordability. With a shortage of affordable housing options, co-housing can be an attractive alternative with some shared resources and costs.

- Shared parenting and the shared cost of childcare.

- Community. Loneliness is a growing societal problem which has been highlighted for many by the pandemic. Co-housing provides a large, extended family to interact with. This is never a requirement but might include cooking and eating together.

- Environmental impact. Many co-living communities share greener living values, and some communities are designed and built specifically for lower energy use. Even if they’re not, sharing resources reduces your environmental footprint.

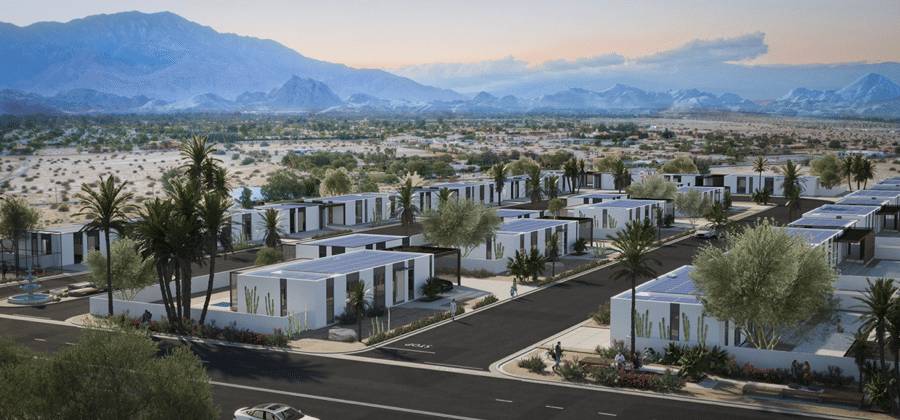

In the 1980s, partners and architects Charles Durrett and Kathryn McCamant went to Denmark to study co-housing. They were intrigued with this Danish concept and set about bringing it to the United States. Together they were instrumental in building many of the co-housing communities that exist today in the US. Charles now leads The Cohousing Company, which designs co-housing projects for a variety of clients. A typical design includes densely packed cottages of 30 or so homes that form a ‘village’, with a liberal sprinkling of communal areas and amenities, occupied by people who want to live co-operatively.

Want to learn more? Read more about how co-housing might provide a path to happiness for modern parents or listen to Charles Durrett and Eve Picker in this Rethink Real Estate (for good) podcast.

Image courtesy of The Cohousing Company